Anna Amanda Smeds

Anna Amanda Smeds, best known by her middle name, was

born 1 July 1889 on the ancestral Smeds estate in Soklot, Finland. She was the sixth and youngest

child of Jakob Herman Mattsson Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs. She grew up on the Soklot

property. When she was only a year old, her mother died. In the wake of that tragedy, her paternal

grandmother Lisa Jakobsdotter Pörkenäs Smeds moved into the home to help her widower son raise his

six kids. Lisa died in 1897. Herman chose not to hire a governess, nor did he remarry. Instead he

was able to count on the help of his brother Erik’s wife Brita, who lived immediately next door.

Anna Amanda Smeds, best known by her middle name, was

born 1 July 1889 on the ancestral Smeds estate in Soklot, Finland. She was the sixth and youngest

child of Jakob Herman Mattsson Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs. She grew up on the Soklot

property. When she was only a year old, her mother died. In the wake of that tragedy, her paternal

grandmother Lisa Jakobsdotter Pörkenäs Smeds moved into the home to help her widower son raise his

six kids. Lisa died in 1897. Herman chose not to hire a governess, nor did he remarry. Instead he

was able to count on the help of his brother Erik’s wife Brita, who lived immediately next door.

While still a teenager, Amanda accompanied her brother Axel and her widower father Herman to

America. Port entry records show the trio arrived in Boston 20 December 1906 aboard the liner

Ivernia out of Liverpool. They came across the continent by train and arrived at the home

of her eldest brother Jakob (Jack) and sister-in-law Annie Rautiainen Smeds in San Francisco. After

the holiday season had ended, they came up to Eureka, Humboldt County, CA, where Amanda’s siblings

Vilhelm (Billy) and Augusta were based.

Amanda spent the interval from early 1907 to 1915 residing in Eureka. A year after her arrival her

father and her brother Billy moved to Reedley, Fresno County, CA, but her siblings Axel and Augusta

remained close by. It is unclear if Amanda shared living quarters with either of these two, though

it does seem likely she would have helped care for her niece Mildred Malm when Mildred was a small

infant in 1908 and 1909. There are surviving photographs from the 1907 to 1912 time period showing

Amanda with Augusta, or with little Mildred, or even with her brother-in-law Fred Malm. Yet the 1910

census does not show her as an occupant in her sister’s home. Unfortunately, Amanda doesn’t seem to

have been enumerated at all in the 1910 census, nor was Axel, so it is difficult to confirm her

circumstances.

Shown at right, Amanda, her young niece

Mildred Malm, and her sister Augusta posing along a street in Eureka in approximately 1912. (The year

is a guess. Mildred looks to be about four years old, and 1912 is when she was that age.) Augusta

is wearing an apron and this suggests she worked nearby, perhaps even inside the store shown in

the background, whose window reads, “Mrs. Goldstein & Miss Woge Proprietors.” Notice how Amanda is

clearly taller than Augusta? Amanda was only five feet two inches tall when this photo was taken and

became shorter still in old age, so without this photographic evidence it would be hard to convince

surviving grandchildren and grand nephews and nieces that she was not the shortest member of

her family.

Shown at right, Amanda, her young niece

Mildred Malm, and her sister Augusta posing along a street in Eureka in approximately 1912. (The year

is a guess. Mildred looks to be about four years old, and 1912 is when she was that age.) Augusta

is wearing an apron and this suggests she worked nearby, perhaps even inside the store shown in

the background, whose window reads, “Mrs. Goldstein & Miss Woge Proprietors.” Notice how Amanda is

clearly taller than Augusta? Amanda was only five feet two inches tall when this photo was taken and

became shorter still in old age, so without this photographic evidence it would be hard to convince

surviving grandchildren and grand nephews and nieces that she was not the shortest member of

her family.

Amanda remained single into her mid-twenties. Among the ways she supported herself was to work at a

cookhouse. Just when she started this occupation is unclear -- perhaps soon after she came to

Eureka, or perhaps not until well into the 1910s. The venue is said to have been what is now known as

the Samoa Cookhouse, though in Amanda’s day it was the Hammond Lumber Company cookhouse. This facility

can still be found in Samoa, a small community on the peninsula across Humboldt Bay from Eureka, still

serving meals seven days a week and still occasionally frequented by lumbermen and paper mill workers

but able to thrive largely due to tourism. The place is considered a historical attraction inasmuch as

it is the only surviving example of the sort of lumber-company cookhouse that could once be found at

various sites within the Redwood Empire. In the early 20th Century the cookhouse at Samoa was a major

employer with a large staff of cooks, waitresses, and housekeepers. Amanda

would not have had time there to do much but work. The following paragraphs, excerpted from the Samoa

Cookhouse Museum brochure, provide a glimpse of what her existence must have been like in those days:

Up until 1915, the cookhouse management had a steadfast rule which said only single women could be

employed. After that time, a few married women were hired. Around the founding year of 1900, and the

years after, girls who worked at the cookhouse were required to reside in the upstairs dormitory.

Waitresses worked seven days a week for five weeks before earning a “day off.” The “day off” was

usually on Sunday. They received $30 a month, including board and room. Each waitress was assigned to

four tables, with ten men per table. As many as ten waitresses were employed regularly.

The girls appeared in the cookhouse kitchen at 6am. They set up tables and fed the “early” men. By 7pm

they usually completed their day’s work. In the summer, they worked until 9pm in the preparation of

vegetables. There was no overtime [pay], but morning and afternoon breaks were permitted.

The splintery wooden floors, scarred by the calked boots

of the pondmen, were scrubbed every Thursday.

Everyone except the boss was provided with a husky broom and a plentiful supply of soapy water. Wearing

rubbers, the girls scrubbed the dining room and the kitchen.

The splintery wooden floors, scarred by the calked boots

of the pondmen, were scrubbed every Thursday.

Everyone except the boss was provided with a husky broom and a plentiful supply of soapy water. Wearing

rubbers, the girls scrubbed the dining room and the kitchen.

When longshoremen were loading ships down at the dock, thirty extra tables were set. Even the girls who

made the beds in the bunkhouses, where the bachelors lived, came in to assist the waitresses. If the

logging train came in from the woods, the girls had to stay and feed the crew.

The cookhouse is likely to have been where Amanda was living and working when a romance culminated between

her and another Finnish immigrant, Charles John Strom. The pair were wed 30 October 1915 in Eureka. Decades

later family members would be left with the impression Amanda and Charlie first met at the cookhouse. This

is unlikely. Surviving documents and photographs suggest they had known each other for years and perhaps

had even met in childhood back in Finland. Certainly Charlie had long been part of Amanda’s sphere of friends

and relatives.

Born Karl Johan Strömsnäs 22 June 1886, Charlie was from Jakobstad. This meant, among other things, that he

was from the same town that Amanda’s mother had come from, a place which in the 1910s was still home to a

great many of Amanda’s cousins on her mother’s side. While Charlie himself was probably not related to Amanda

by blood (or at least not closely enough to matter in the grand scheme of things), the two probably shared

myriad genealogical connections through various marriages between denizens of that small, lightly populated

corner of Finland, even if the documentation might not exist to spell out those connections in a coherent

fashion.

Charlie’s story prior to him marrying Amanda goes like this: He appears to have been the only child of

Andrew Strom (Anders Strömsnäs) and Louisa Estromones. Anders Strömsnäs apparently died when Charlie was

quite small. His mother next married a man named Polander, and it was in their home that Charlie grew up.

He was raised with a slightly younger half-brother or stepbrother, Vilhelm Polander, better known as Vill.

Like many Swedish-Finns, Charlie probably was just as likely in the old country to introduce himself by the

last name of Andersson as he was to say it was Strömsnäs. The latter is a place name, and hints that his

father or grandfather or great-grandfather came from the village of that name several miles inland from

Jakobstad and Soklot. Becoming a Strom later on was not just a matter of shortening his name. A typical

American would see the name and assume it was pronounced to rhyme with “bomb.” Charlie went along with this

rather than try to correct an endless succession of acquaintances. But in Finland, the syllables in

Strömsnäs rhyme with “brooms” and “grass.”

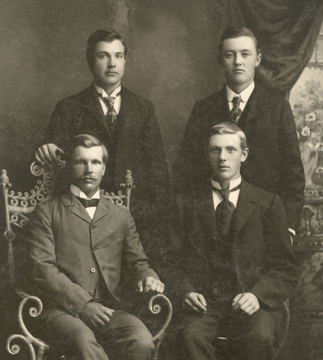

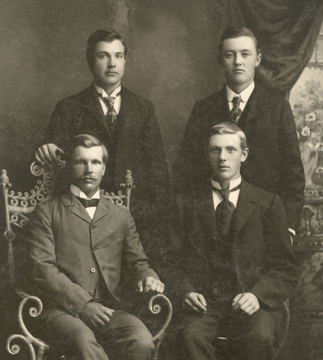

Charlie came to the U.S. for the first time in 1903,

departing even before turning seventeen. He was not alone on the journey. He came with three other young

men. These three, along with Charlie, are identified by last name on the back of the photograph shown at

right, taken at John Christensen studio in Duluth, MN. The two in back were named Salo and Karlsson.

Charlie is the figure at the lower right. Beside him on the left is his very good buddy Charles Lingonblad

(the name was Karl Hjalmar Lingonblad in Finland), born 3 March 1883.

Charlie came to the U.S. for the first time in 1903,

departing even before turning seventeen. He was not alone on the journey. He came with three other young

men. These three, along with Charlie, are identified by last name on the back of the photograph shown at

right, taken at John Christensen studio in Duluth, MN. The two in back were named Salo and Karlsson.

Charlie is the figure at the lower right. Beside him on the left is his very good buddy Charles Lingonblad

(the name was Karl Hjalmar Lingonblad in Finland), born 3 March 1883.

How long Charlie stayed in Duluth is not known. Probably not more than a year and perhaps as little as a

few days. He came on to Eureka, perhaps with all three of his companions but certainly with Charles

Lingonblad, who would go on to reside in Humboldt County until his death many decades later. Charlie soon

found work as a logger. The redwood forests may have been where he first met Jack and/or Billy

Smeds and struck up a co-worker acquaintance. The reason to say “may” is that Charlie could easily have met

the Smeds boys in Finland. Whether it was the old-country connections or the camaraderie born of laboring

thousands of miles from home alongside others with whom he shared a similar origin, the result was that a

tight bond manifested between Charlie and the Smeds brothers, an affection that extended to younger brother

Axel Smeds when he arrived. A photograph confirms this. Charlie Strom,

Billy Smeds, and Axel Smeds appear together in a formal, studio photograph in their Sunday clothes. That is

to say, the image stemmed from a scheduled posing session with a professional photographer. It must have

been taken in part to send to family and friends back home. The artifact could only have been created in

1907. All three men appear to be in their early twenties, and it was only in calendar year 1907 that both

Billy and Axel Smeds dwelled in Eureka. Axel arrived in January of that year, while Billy moved away to

Fresno County in December. Thus, Charlie surely knew Amanda by 1907. Her brothers must have introduced the

two if they had not met before in Finland.

The puzzle, of course, is why if Charlie and Amanda knew each other so early on, why did they wait until

1915 to get hitched? It doesn’t seem to be a lack of interest. Once they finally were married, they doted

upon one another. Some of the explanation might be that Charlie simply was not around Amanda much for at

least some of that span. He was gone from Eureka for at least a couple of years. In a newspaper article

published in honor of his 80th birthday, it is mentioned that Charlie returned to Finland on two occasions.

One visit was in 1948 in order to see his mother, stepfather, and half-brother. But the first time was in

1908. His return passport survives among the mementoes currently in the possession of his granddaughter,

showing that he departed Jakobstad in September, 1910.

In the end, Charlie and Amanda did get together. The catalyst may have been Charles Lingonblad. The two

Charlies -- Lingonblad and Strom -- remained close buddies. In the early 1910s, Lingonblad struck up a

romance with a woman named Hannah Wickman. This in turn seems to have drawn Amanda and Charlie into

frequent social contact.

Amanda Smeds and Charlie Strom, their wedding portrait

Who was Hannah Wickman? She was very likely a second cousin to the Smeds brothers and sisters. Wickman is

a form of the name Vikman, as in Vik. This means Hannah -- it was Johanna in the old country -- must have

been of the same Vik family that owned a third of the Soklot estate. Herman Smeds had found his bride

Greta Fagernäs when she was working as a servant on the Vik estate. Soklot was (and is) a very small place,

just a handful of homes at the dead-end of a country lane. Herman’s kids would have known their Vik kinfolk

very well, having grown up as elbow-to-elbow neighbors. Anyone who lived at Soklot, be they third or fourth

cousins or whatever, would have felt like siblings or first cousins in terms of familiarity. Hannah, born

17 February 1885, was only four years Amanda’s senior and was likely a cherished companion

in Eureka, where so many people were strangers who didn’t even speak the language Amanda knew best. The

photograph of the three women shown above left next to the text about the cookhouse is of Amanda, center,

and two Finnish cousins. The photo was taken at Seeley studio in Eureka, so it is not an image of Amanda

before she immigrated. (It is also not precisely a photo of them taken together. The original print shows

signs that the pose was manufactured in the darkroom by compositing shoulders-and-head sections taken

from separate shots.) Alas, Amanda did not write any names on the back of the photo during her lifetime,

and after her death the best her offspring could recall was that the pair were cousins of hers of some

sort. One of the women is almost sure to have been Hannah Wickman.

When Hannah and Charles Lingonblad’s romance deepened, it would have set up a double-date courtship scenario.

Both couples ended up getting married. Amanda and Charlie got there first. Their marriage certificate

survives. The witnesses on that document are Charles Lingonblad and Hannah Wickman -- the use of Hannah’s

maiden name demonstrating she was not yet a bride. The 1930 census makes it clear that she and Charles must

have had their own wedding very shortly after Charlie and Amanda had theirs. And speaking of maiden names,

Hannah’s mother’s maiden name (as shown on Hannah’s California Death Index entry) is intriguing. It was

Beck, or as written in Finland, Bäck. This was the maiden last name of the mother of Ina Marie Jacobson

(Jakobsson), wife of Axel Smeds. Ina Marie and Axel’s wedding was yet another mid-1910s Eureka event. All

of this suggests Hannah Wickman may have been simultaneously a cousin of both Ina Marie and the Smeds

siblings.

The Lingonblads remained in Humboldt County for good, Charles dying there 1 August 1952 and Hannah perishing

8 May 1968. The Stroms charted an entirely different course. Immediately after becoming husband and wife,

Amanda and Charlie moved down to Reedley. For a few weeks or even a few months, they stayed with Billy Smeds

and his wife Marie and their two little boys, Roy and Alfred, in their farmhouse on the bluff of the Kings

River north of town. Inasmuch as Jack Smeds and family had also chosen that point in time to move down to

Reedley, the living arrangement was very cozy. (A photograph of the house in 1915 is shown in the midst

of the biography of Amanda’s sister-in-law Maria Rautiainen Smeds, found elsewhere on this website.)

Soon Jack and Annie’s new house was ready for them, and by early 1916, Amanda and Charlie acquired a farm on

Alta Avenue, about two miles to the east of her brothers’ parcels. The Alta Avenue place would be Amanda

and Charlie’s place of residence for the next forty years.

Charlie, like most farmers in the immediate area north of Reedley, grew grapes -- mostly for raisins.

The children arrived in short order, Agnes in 1916, Karin in 1918, and Frances in 1920. With the latter

birth, the first American generation of the Herman Smeds clan was complete, with the exception of two

babies born to Augusta Malm in the early 1920s who both died the same day they were born. Amanda happily

took up her role as a homemaker and mother. She was not yet quite done with being a wage-earner outside

the home, though. The Strom farm was only twenty acres, and the resulting raisin income not enough

to depend upon, particularly because an unseasonal rain could wipe out the crop any given year. Charlie’s

pattern was to go to work in the fruit-packing houses during those portions of the harvest season when he

did not have to tend to his own crop. Amanda put in hours at packing houses as well. Usually what was

being packed was table grapes, though sometimes it was peaches and in the winter, oranges. (Amanda and

Charlie had orange trees themselves, as one can see in the background of the photo shown slightly below

left, but just a few for home use.) To further bolster the household treasury, the couple raised

chickens. This was not just a sideline. Their chicken houses at any particular point in time contained

as many as two thousand birds. The dual occupation meant Charlie was a member of both the Sun Maid

Raisin Growers Association and the California Poultry Producers Association.

Charlie’s years as a logger had left him well-prepared in the physical-strength sense to be a farmer.

Amanda’s nephew Alfred Smeds once referred to Charlie’s muscle power in a tone of awe, describing how once

when a plow had become unhitched from a tractor out in a vineyard and Alfred and his brother Roy were

about to fetch a steel bar to lever the equipment back into alignment to reattach it, Charlie simply picked

up the plow and set it into place. (In later years, younger male relatives understood that to shake ol’

Charlie Strom’s hand, one had to be prepared to expect the grip of someone who had spent his whole working

life at the sort of labor that might break a weaker individual.)

Amanda and Charlie’s experience as an immigrant couple

differed from that of Billy and Jack and their wives. Both of her brothers had married women whose native

language was Finnish, not the Swedish that the Smedses spoke as members of the ethnic minority in their

mother country. Though Billy and Jack did learn some Finnish -- for Jack it was one of several languages

in which he became fluent -- the reasonable compromise in the two households was to use English. It is

fair to say that their kids -- Roy and Al Smeds, and Sylvia, Lillian, and Lawrence Smeds -- grew up using

English as their first language. This was less so in the Strom household. Amanda and Charlie naturally

tended to speak their native Swedish with one another, and the kids imitated them to such an extent that

when Agnes entered school, her unfamiliarity with English was enough to make her fake illness so as to get

to stay home. This was enough of an issue that Amanda and Charlie and the school staff all agreed that

Agnes should be allowed to start school a year later, when her maturity -- and hopefully some practice

with English -- would allow her to better deal with the challenge.

Amanda and Charlie’s experience as an immigrant couple

differed from that of Billy and Jack and their wives. Both of her brothers had married women whose native

language was Finnish, not the Swedish that the Smedses spoke as members of the ethnic minority in their

mother country. Though Billy and Jack did learn some Finnish -- for Jack it was one of several languages

in which he became fluent -- the reasonable compromise in the two households was to use English. It is

fair to say that their kids -- Roy and Al Smeds, and Sylvia, Lillian, and Lawrence Smeds -- grew up using

English as their first language. This was less so in the Strom household. Amanda and Charlie naturally

tended to speak their native Swedish with one another, and the kids imitated them to such an extent that

when Agnes entered school, her unfamiliarity with English was enough to make her fake illness so as to get

to stay home. This was enough of an issue that Amanda and Charlie and the school staff all agreed that

Agnes should be allowed to start school a year later, when her maturity -- and hopefully some practice

with English -- would allow her to better deal with the challenge.

Many of the other Finns of the Reedley area belonged to the United Finnish Kaleva Brothers and Sisters,

Lodge No. 20. However, this group had such a “Finnish-Finn” emphasis that the “Finland Swedes” -- as

they called themselves -- were motivated to start their own lodge, where Swedish language and customs

would prevail. Accordingly, Charlie, along with Andrew A. Westerlund, a bachelor neighbor and good

friend of Jack and Billy Smeds, organized a chapter of the charity society, the Order of Runeburg. The

two men alternated as president and treasurer throughout its existence. The lodge met once a month on

Sunday afternoons. In the summertime, the members gathered on the Kings River sandbar and beach on the

farm of Charles and Aina Klockars. Otherwise they met in members’ homes. Because there were more Swedes

concentrated in Kingsburg, the lodge is usually described as a Kingsburg lodge, though all of the Reedley

Finland-Swedes belonged except Jack and Billy Smeds, who already belonged to UFKBS Lodge #20 because of

their wives and apparently did not have the time to participate in the functions of the Order of Runeburg

as well. The Kingsburg chapter eventually faded out. Thereafter Charlie and Amanda and a few others

occasionally attended meetings of the chapter in Bakersfield (seventy-five miles to the south of

Reedley).

It may have been Amanda and Charlie’s leisurely assimilation into English-speaking and American

bureaucracy that kept them from pursuing citizenship until well after her brothers. Jack

Smeds had become a citizen in 1906, Billy in 1912, Axel in 1915. Amanda did not become a citizen until

16 May 1928. This was six months after Charlie, whose naturalization date was 23 November 1927. In her

family, Amanda’s example was echoed only by her sister Augusta, who was naturalized in the 1920s about

a quarter century after her arrival in the country. Augusta, it is worth noting, was like her sister in

possessing a spouse who shared her native tongue.

In 1955, having raised Agnes, Karin, and Frances to adulthood

on the farm and witnessed them head out into the world, Amanda and Charlie retired three miles south into

the town of Reedley. Their home on Linden Avenue was a traditional gathering place of the Smeds clan at

Easter through the 1960s and into the 1970s. That holiday was the perfect time to enjoy Amanda’s garden,

which was a marvel. She had a penchant for tulips.

In 1955, having raised Agnes, Karin, and Frances to adulthood

on the farm and witnessed them head out into the world, Amanda and Charlie retired three miles south into

the town of Reedley. Their home on Linden Avenue was a traditional gathering place of the Smeds clan at

Easter through the 1960s and into the 1970s. That holiday was the perfect time to enjoy Amanda’s garden,

which was a marvel. She had a penchant for tulips.

Amanda was the only one of her birth family to live past eighty, and was the only survivor left after

the 1964 death of her brother Billy. Fortunately she remained vigorous and keen-minded. This was doubly

fortunate because Charlie “faded out” early, becoming less certain what day it was and having trouble

remembering the identities of people with whom he did not have regular contact. He maintained a cheerful

and cooperative disposition, though, and with Amanda to look after him, he was able to remain at home on

Linden Avenue.

In extreme old age, Amanda played a key role in reestablishing contact with the branch of the family

that had remained in Soklot. Her nephew Alfred visited the old homestead in the summer of 1973 and was

greeted there by a man named Sven Eriksson. Due to language problems (Alfred understanding English and

Finnish but not Swedish, the only language Sven knew), it wasn’t clear who Mr. Eriksson was, except that

he was the occupant of the home in which Amanda and her siblings had been born. When Amanda was told of

the encounter, she replied that Sven was a cousin and wrote to him in Swedish. By request, Sven sent

multiple copies of the chapbook Smeds i Soklot, and had his daughter Karita Sjöholm, who spoke

English and was then a resident of Ireland, compose a letter to Alfred.

Finally Amanda became so frail and Charlie was so affected by his Alzheimer’s Disease that it was no

longer viable for them to remain in the Linden Avenue home. Agnes arranged for them to move into an

elder care facility not far from her home, which was in Visalia, Tulare County, CA, half an hour’s

drive south of Reedley. The move was made in early 1974. Amanda passed away at that facility 20 April

1974 (the night of the nineteenth). Charlie’s stay was far longer. Even though his body was still

robust, his mental deterioration was such that he could not get by without round-the-clock supervision.

However, Agnes made sure to fetch him and bring him along whenever there was a family gathering at her

house or in Reedley. This custom continued right up until his final year of life. He always greeted

everyone with a smile. Heartbreakingly for those

listening but perhaps better for him, his dementia by then was deep enough that he would sometimes ask if

Amanda -- “Mama” he would say to Agnes -- was going to join them for the meal. Charlie finally perished

in Visalia 24 July 1980 at the age of ninety-four. The graves of wife and husband can be found at Reedley

Cemetery.

Amanda and Charlie with their daughters, both sons-in-law, and both grandchildren at

their fiftieth wedding anniversary party in 1965.

Children of Anna Amanda Smeds

with Charles John Strom

Agnes Margaret

Strom

Karin Anna

Strom

Frances Amanda

Strom

To return to the Smeds Family History main page, click here.

Anna Amanda Smeds, best known by her middle name, was

born 1 July 1889 on the ancestral Smeds estate in Soklot, Finland. She was the sixth and youngest

child of Jakob Herman Mattsson Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs. She grew up on the Soklot

property. When she was only a year old, her mother died. In the wake of that tragedy, her paternal

grandmother Lisa Jakobsdotter Pörkenäs Smeds moved into the home to help her widower son raise his

six kids. Lisa died in 1897. Herman chose not to hire a governess, nor did he remarry. Instead he

was able to count on the help of his brother Erik’s wife Brita, who lived immediately next door.

Anna Amanda Smeds, best known by her middle name, was

born 1 July 1889 on the ancestral Smeds estate in Soklot, Finland. She was the sixth and youngest

child of Jakob Herman Mattsson Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs. She grew up on the Soklot

property. When she was only a year old, her mother died. In the wake of that tragedy, her paternal

grandmother Lisa Jakobsdotter Pörkenäs Smeds moved into the home to help her widower son raise his

six kids. Lisa died in 1897. Herman chose not to hire a governess, nor did he remarry. Instead he

was able to count on the help of his brother Erik’s wife Brita, who lived immediately next door. Shown at right, Amanda, her young niece

Mildred Malm, and her sister Augusta posing along a street in Eureka in approximately 1912. (The year

is a guess. Mildred looks to be about four years old, and 1912 is when she was that age.) Augusta

is wearing an apron and this suggests she worked nearby, perhaps even inside the store shown in

the background, whose window reads, “Mrs. Goldstein & Miss Woge Proprietors.” Notice how Amanda is

clearly taller than Augusta? Amanda was only five feet two inches tall when this photo was taken and

became shorter still in old age, so without this photographic evidence it would be hard to convince

surviving grandchildren and grand nephews and nieces that she was not the shortest member of

her family.

Shown at right, Amanda, her young niece

Mildred Malm, and her sister Augusta posing along a street in Eureka in approximately 1912. (The year

is a guess. Mildred looks to be about four years old, and 1912 is when she was that age.) Augusta

is wearing an apron and this suggests she worked nearby, perhaps even inside the store shown in

the background, whose window reads, “Mrs. Goldstein & Miss Woge Proprietors.” Notice how Amanda is

clearly taller than Augusta? Amanda was only five feet two inches tall when this photo was taken and

became shorter still in old age, so without this photographic evidence it would be hard to convince

surviving grandchildren and grand nephews and nieces that she was not the shortest member of

her family. The splintery wooden floors, scarred by the calked boots

of the pondmen, were scrubbed every Thursday.

Everyone except the boss was provided with a husky broom and a plentiful supply of soapy water. Wearing

rubbers, the girls scrubbed the dining room and the kitchen.

The splintery wooden floors, scarred by the calked boots

of the pondmen, were scrubbed every Thursday.

Everyone except the boss was provided with a husky broom and a plentiful supply of soapy water. Wearing

rubbers, the girls scrubbed the dining room and the kitchen. Charlie came to the U.S. for the first time in 1903,

departing even before turning seventeen. He was not alone on the journey. He came with three other young

men. These three, along with Charlie, are identified by last name on the back of the photograph shown at

right, taken at John Christensen studio in Duluth, MN. The two in back were named Salo and Karlsson.

Charlie is the figure at the lower right. Beside him on the left is his very good buddy Charles Lingonblad

(the name was Karl Hjalmar Lingonblad in Finland), born 3 March 1883.

Charlie came to the U.S. for the first time in 1903,

departing even before turning seventeen. He was not alone on the journey. He came with three other young

men. These three, along with Charlie, are identified by last name on the back of the photograph shown at

right, taken at John Christensen studio in Duluth, MN. The two in back were named Salo and Karlsson.

Charlie is the figure at the lower right. Beside him on the left is his very good buddy Charles Lingonblad

(the name was Karl Hjalmar Lingonblad in Finland), born 3 March 1883.

Amanda and Charlie’s experience as an immigrant couple

differed from that of Billy and Jack and their wives. Both of her brothers had married women whose native

language was Finnish, not the Swedish that the Smedses spoke as members of the ethnic minority in their

mother country. Though Billy and Jack did learn some Finnish -- for Jack it was one of several languages

in which he became fluent -- the reasonable compromise in the two households was to use English. It is

fair to say that their kids -- Roy and Al Smeds, and Sylvia, Lillian, and Lawrence Smeds -- grew up using

English as their first language. This was less so in the Strom household. Amanda and Charlie naturally

tended to speak their native Swedish with one another, and the kids imitated them to such an extent that

when Agnes entered school, her unfamiliarity with English was enough to make her fake illness so as to get

to stay home. This was enough of an issue that Amanda and Charlie and the school staff all agreed that

Agnes should be allowed to start school a year later, when her maturity -- and hopefully some practice

with English -- would allow her to better deal with the challenge.

Amanda and Charlie’s experience as an immigrant couple

differed from that of Billy and Jack and their wives. Both of her brothers had married women whose native

language was Finnish, not the Swedish that the Smedses spoke as members of the ethnic minority in their

mother country. Though Billy and Jack did learn some Finnish -- for Jack it was one of several languages

in which he became fluent -- the reasonable compromise in the two households was to use English. It is

fair to say that their kids -- Roy and Al Smeds, and Sylvia, Lillian, and Lawrence Smeds -- grew up using

English as their first language. This was less so in the Strom household. Amanda and Charlie naturally

tended to speak their native Swedish with one another, and the kids imitated them to such an extent that

when Agnes entered school, her unfamiliarity with English was enough to make her fake illness so as to get

to stay home. This was enough of an issue that Amanda and Charlie and the school staff all agreed that

Agnes should be allowed to start school a year later, when her maturity -- and hopefully some practice

with English -- would allow her to better deal with the challenge. In 1955, having raised Agnes, Karin, and Frances to adulthood

on the farm and witnessed them head out into the world, Amanda and Charlie retired three miles south into

the town of Reedley. Their home on Linden Avenue was a traditional gathering place of the Smeds clan at

Easter through the 1960s and into the 1970s. That holiday was the perfect time to enjoy Amanda’s garden,

which was a marvel. She had a penchant for tulips.

In 1955, having raised Agnes, Karin, and Frances to adulthood

on the farm and witnessed them head out into the world, Amanda and Charlie retired three miles south into

the town of Reedley. Their home on Linden Avenue was a traditional gathering place of the Smeds clan at

Easter through the 1960s and into the 1970s. That holiday was the perfect time to enjoy Amanda’s garden,

which was a marvel. She had a penchant for tulips.