Augusta Sofia Smeds

Augusta Sofia Smeds, second child and eldest daughter

of Jakob Herman Mattsson Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs, was born 9 November 1882 on the

ancestral Smeds estate in Soklot in the parish of Nykarleby, Finland, a place that would continue

to be her home throughout her childhood, as it had been home to many generations of Smedses. She

was nicknamed Gusta, though nearly all surviving records refer to her by her formal name.

Augusta Sofia Smeds, second child and eldest daughter

of Jakob Herman Mattsson Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs, was born 9 November 1882 on the

ancestral Smeds estate in Soklot in the parish of Nykarleby, Finland, a place that would continue

to be her home throughout her childhood, as it had been home to many generations of Smedses. She

was nicknamed Gusta, though nearly all surviving records refer to her by her formal name.

After Augusta, the family expanded four more times, until she was one of six children. There might

have been even more, but her mother caught a cold that deepened into pneumonia, and she died in

early 1891. Augusta was the eldest girl, but at eight years old she was too young to function as

the “woman of the family.” While her father went on to do a remarkably good job as a single

parent, naturally Augusta and her siblings needed a surrogate mother. That role was filled by her

paternal grandmother Lisa Jakobsdotter Pörkenäs Smeds. The latter had been an important part of

Augusta’s life all along, as well as a familiar presence given that Lisa had dwelled right next

door as part of the household of her older son, Erik. With Greta’s passing, Lisa moved in with

Herman and his youngsters. Unfortunately Lisa had already entered her seventies by the dawn of

that decade, and she did not live long enough to see any of the six kids complete their childhoods.

She died in the summer of 1897. At this point, Augusta was fourteen and a half and her father

apparently did not feel it was necessary to arrange for another female of mature years to be

inserted into the household. Instead Augusta took on more responsibility, even as she her siblings

were looked after by their uncle Erik’s wife Brita. Erik and Brita’s own children were all adults

by then with one exception, so it is was logistically reasonable for Brita to take on the additional

responsibility.

In a steady progression over a period of not quite a decade, Herman’s kids set out to begin their

independent lives. It was customary for this to happen before each of them turned eighteen. This was

not a “kick in the butt” sort of disengagement, nor was it an expression of “Oh, my God, I can’t

stand it here anymore!” Instead the precocious leavetakings demonstrate how capable, responsible, and

confident all six were. Augusta’s older brother Jakob even departed before turning sixteen, though

it should be noted he did so by accepting an offer to become a boarding apprentice to a goldsmith in

Jakobstad, and he was not truly on his own that early. In fact, he may have been under even more

oversight than he had been subject to at Soklot. Augusta’s turn was next. The parish registers, the

so-called husförhör volumes, reveal that Augusta left home in the year 1900 to move to Vasa.

(This is the Swedish spelling, preferred by Ostrobothnians of the era over the official Russian name,

Nikolaistad. In modern times, the city name is usually rendered as Vaasa, its Finnish-language

variation.) It is not entirely clear why Augusta chose Vasa, except perhaps that it was a bit farther

off than the day-trip-distance choices of Nykarleby village or the port town of Jakobstad, and maybe

Augusta wanted to demonstrate she could get by completely on her own. That sort of speculation aside,

the choice was logical. Vasa was in the midst of some economic upheaval, but in 1900 could still boast

of a certain amount of opportunity for a young woman entering the workforce. Moreover, it was still

within the region of Ostrobothnia, where the customs and language (Swedish) were in keeping with what

Augusta knew. (It was in fact the capital of the region.) Those advantages would not have been true

of most other parts of Finland.

Not long after Augusta settled in Vasa, her brother Jakob chose to emigrate to the United States,

following in the wake of various neighbors, friends, and relatives who reacted to the dwindling

prosperity of Ostrobothnia by starting afresh in America. While many Finns chose to head to such places

as Michigan, Minnesota, or the Pacific Northwest, Jakob went to Eureka, Humboldt County, CA. Several

relatives were already based there, including Leander Fagernäs, one of their mother’s first cousins.

Within another couple of years, it was clear that younger brother Vilhelm would soon be in danger of

being forcibly conscripted into the Russian army, and so a plan was made to have him join Jakob in

order to get him out of harm’s way before he turned eighteen and was forced to “serve.” As a female,

Augusta was not under the same threat, but heading to America was equally valid for her as a chance

to thrive over the long run. Husförhör notations and other sources confirm she made her

journey to Eureka in 1904. This timing suggests she went with Vilhelm. He is known to have set out

from home 30 March 1904, proceeding by way of Southhampton, England, where he boarded the S.S. St.

Louis 16 April 1904. The voyage ended in New York 23 April 1904. These facts about his

trans-Atlantic crossing are known from his passport, not a ship manifest that would have clarified

whether he had a family member as a travel companion. Perhaps Augusta made her trip at some other

point in the calendar year. There are, however, no direct indications that was the case. Meanwhile a

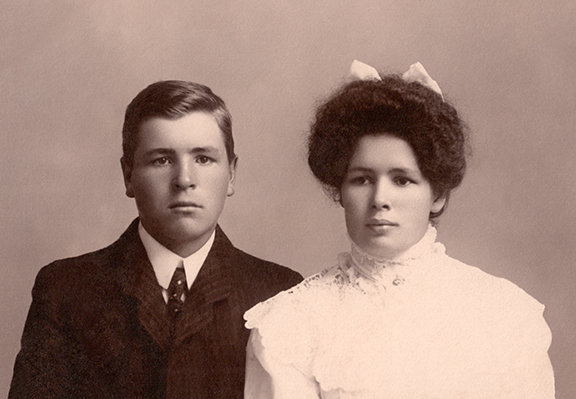

number of clues support the contention that she came in tandem with her brother. Among them is the

photo shown immediately below, which would appear to been taken not long after their arrival in

Eureka, probably in order to be able to send a copy home to their father in Soklot.

Augusta Sofia Smeds and her brother Vilhelm in Eureka, 1904 or 1905. Photograph by

Joshua Van Sant, Jr. (1861-1950) taken at his studio at 310 F Street.

By happenstance, she and Vilhelm -- who would now begin Americanizing his name to William, and who

was often called Billy by his female relatives -- became residents of Humboldt County just as Jakob

(becoming known as Jack) obtained a job as a silversmith for the big jewelry firm, Shreve & Company,

and as a consequence, relocated to San Francisco. Augusta and Billy may have weighed the possibility

of also making San Francisco their base of operations, but they chose to stay. Not only were they

accustomed to communities of vastly smaller size than San Francisco, but Billy was well suited to

employment as a timber cutter in the redwoods, being healthy, young, strong, and also tall, the

latter trait making him the exception among his immediate family members. Moreover, the pair were

immersed in a milieu replete with many other Finland Swedes, including a number of cousins on their

mother’s side. Leander Fagernäs had died in 1902, but his widow and kids were still in place, and

there were others relatives as well, some that Augusta had already been acquainted with in Finland,

and some she came to know for the first time in America, but who she knew she could count on to help

her adjust to her new surroundings.

A natural means to mingle and get to know other immigrants from Ostrobothnia was by participating

in the social functions of the Order of Runeberg. The lodge in Eureka was very active. Augusta took

advantage. It may well have been through that means of social engagement that she became acquainted

with the man who would soon become her husband. He was Isak Alfred Malm. This became Americanized to

Isaac, but in fact he barely used either Isak or Isaac. He was known by his middle name and from

this part of his life onward he was almost always called Fred. He was a son of Isak Malm and Johanna

Smeds or Smede of the village of Lappfjärd in the southern part of Ostrobothnia. If his mother’s

maiden name was Smeds, as shown on his death certificate, that naturally leads to the question, were

he and Augusta related? Furthermore, there is some indication he spent his final years in Finland (his

late teenage years) residing in the city of Vasa, some sixty miles north of Lappfjärd. This was right

when Augusta was in that very community, which also is enough to make a person wonder if he knew

Augusta prior to the time they found themselves at the same lodge meetings in Eureka. But even assuming

that was when they were introduced, the pair had not had much chance to engage in a courtship while in

the old country. Fred had emigrated in 1902. He had arrived in Eureka in 1903 after a year in Colorado.

One thing is certain. It was in Eureka that their romance blossomed. They were very well suited and

would go on to forge a rock-solid marital partnership. Even in terms of age they were superbly

compatible. Fred’s date of birth was either 5 June 1882 or 5 June 1883, meaning he was Augusta’s

senior by only five months or her junior by only seven.

Fred (shown left) had left behind much of his family in

the mother country, but not quite all -- his slightly younger brother Victor (full name Johan Victor

Isaksson Malm, which was Americanized to John Victor Malm) also came to live in Eureka, and in

decades to come Fred would be uncle to a niece, Vera, and a nephew, Shirley (aka Oliver). (Another

nephew, Victor Harold Malm, died in infancy.) The Malm brothers may have been part of the well-known

Malm clan of Vasa province. That clan had grown rich in the 1700s and early 1800s as owners of a major

commercial empire based upon shipbuilding. As described in Augusta’s father’s biography, Ostrobothnia

was the place to build ships during that era. Alas, Finland had lost its dominance in the

industry because no matter how well-suited the region had been for the construction of vessels made

of wood and tar, it enjoyed no advantage at all once shipbuilding came to depend upon steel. Fred and

his brother apparently were not the beneficiaries of a trove of legacy wealth. This appears to have

been a sore point. The brothers’ endowment was so paltry they were essentially compelled to emigrate so

that their shares of their birthright could go to their younger sister Emilia Adelina, who stayed in

Finland lifelong. Fred remained so bitter about being “sent into exile” he would only communicate in

English, refusing to fall back on Swedish even when among other immigrants who loved to chat in their

mother tongue when possible. However, it is fair to say the fact that some of his recent forebears

had enjoyed privileged lives spurred him to improve his own circumstances -- and by extension improve

Augusta’s circumstances. Moreover, he “thought like a rich man.” That is to say, he devoted himself

to finding ways to use capital and investments to make money, not just to earn income entirely through

personal labor and wages.

Fred (shown left) had left behind much of his family in

the mother country, but not quite all -- his slightly younger brother Victor (full name Johan Victor

Isaksson Malm, which was Americanized to John Victor Malm) also came to live in Eureka, and in

decades to come Fred would be uncle to a niece, Vera, and a nephew, Shirley (aka Oliver). (Another

nephew, Victor Harold Malm, died in infancy.) The Malm brothers may have been part of the well-known

Malm clan of Vasa province. That clan had grown rich in the 1700s and early 1800s as owners of a major

commercial empire based upon shipbuilding. As described in Augusta’s father’s biography, Ostrobothnia

was the place to build ships during that era. Alas, Finland had lost its dominance in the

industry because no matter how well-suited the region had been for the construction of vessels made

of wood and tar, it enjoyed no advantage at all once shipbuilding came to depend upon steel. Fred and

his brother apparently were not the beneficiaries of a trove of legacy wealth. This appears to have

been a sore point. The brothers’ endowment was so paltry they were essentially compelled to emigrate so

that their shares of their birthright could go to their younger sister Emilia Adelina, who stayed in

Finland lifelong. Fred remained so bitter about being “sent into exile” he would only communicate in

English, refusing to fall back on Swedish even when among other immigrants who loved to chat in their

mother tongue when possible. However, it is fair to say the fact that some of his recent forebears

had enjoyed privileged lives spurred him to improve his own circumstances -- and by extension improve

Augusta’s circumstances. Moreover, he “thought like a rich man.” That is to say, he devoted himself

to finding ways to use capital and investments to make money, not just to earn income entirely through

personal labor and wages.

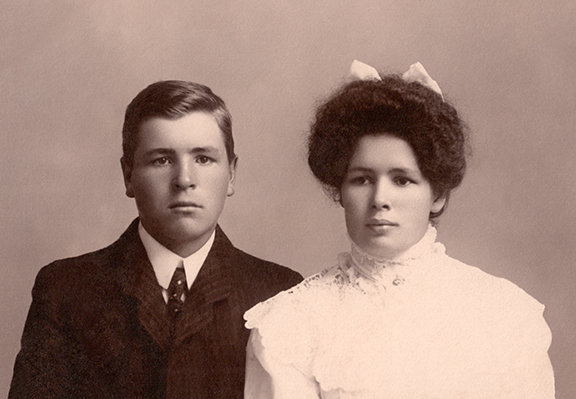

Augusta and Fred’s wedding date is not precisely known (even though, as you can see below, the

photograph taken in honor of the big day is still secure within the family memorabilia). It was

probably in the spring or summer of 1907. It was her personal big-deal moment in the midst of a

four-year span rich with eventful happenings affecting her family. Jack’s move to the big city was

among the early developments. Then at the end of 1904 or in January, 1905, her sister Maria set out

for America. Maria’s destination was Eureka. She didn’t make it, though. She met a man on the voyage

across the Atlantic and by the time the ocean liner reached port, she had agreed to marry him. Instead

of joining Billy and Augusta in the redwood empire, she settled with her new husband in northern New

Hampshire.

Maria’s departure meant Herman Smeds was left with only his youngest two kids as yet

unfledged -- Axel and Amanda. With title to the Soklot farm having already passed into the hands

of Herman’s nephew Johan Eriksson, the time was ripe for a clean break. All three remaining family

members left Finland at the end of 1906. After spending a number of weeks in San Francisco at the

home Jack shared with his new wife, Anna Rautiainen, they completed the final leg of the journey

and reached Eureka in late January or in February, 1907. With Billy off in the forests every

workday cutting trees, it was Augusta who helped get her father and youngest siblings adjusted to

their new national and cultural environment. They meanwhile were able to cheer her on as she began

her life as a married woman -- which probably includes being there as attendees at her wedding,

assuming that event happened after their arrival, which seems to have been the case.

She would only get to have her father near at hand

for less than a complete calendar year. At the end of 1907, he and Billy left Eureka for good,

proceeding down to Fresno County to take up active management of the farm Jack had purchased north of

the small town of Reedley, but which Jack could not personally oversee because needed to stay put and

hold on to his good-paying job at Shreve & Company. Augusta was undoubtedly wistful at the absence of

these loved ones, but the fact is, she was far too busy to dwell upon the circumstance. For one thing,

she was reaching the end of her first pregnancy. Daughter Mildred Augusta Malm was born in the middle

of March, 1908. (Shown at right, Augusta and Mildred. There was no date written on the original

photograph, but judging by Mildred’s apparent age it would seem to have been taken in 1910 or 1911.)

She would only get to have her father near at hand

for less than a complete calendar year. At the end of 1907, he and Billy left Eureka for good,

proceeding down to Fresno County to take up active management of the farm Jack had purchased north of

the small town of Reedley, but which Jack could not personally oversee because needed to stay put and

hold on to his good-paying job at Shreve & Company. Augusta was undoubtedly wistful at the absence of

these loved ones, but the fact is, she was far too busy to dwell upon the circumstance. For one thing,

she was reaching the end of her first pregnancy. Daughter Mildred Augusta Malm was born in the middle

of March, 1908. (Shown at right, Augusta and Mildred. There was no date written on the original

photograph, but judging by Mildred’s apparent age it would seem to have been taken in 1910 or 1911.)

Having Mildred was clearly a priority and meant the world to Augusta and Fred, but they nevertheless

did not expand their family any further in the near term. This stands in contrast to the actions of all

five of her siblings, who though they had small families of only two to four children, produced them at

quick intervals during the very earliest years of their marriages. Augusta and Fred chose a different

course. Augusta did not restrict her efforts to being a housewife and mother. Aside perhaps from the

first year or two of Mildred’s life, Augusta earned a significant portion of the couple’s income. As a

tandem, Augusta and Fred had a plan. They set out to work hard during the rest of their twenties and

into their thirties, while they had plenty of energy, in order to get themselves on such a solid

financial footing they could kick back and enjoy themselves in subsequent decades. The scheme was

ambitious and would involve plenty of effort and determination, but as it happens, they had what it

took to succeed.

Whenever possible, Fred took advantage of opportunities that would allow him to become more a common

laborer. As a newly-minted immigrant he had been obliged to resort to any job he could get. While in

Colorado, he had worked as a miner. In Eureka he had been a woodsman -- the lumber companies were

always hiring men to fill out their crews in the redwoods. Fred put in his turn at these back-breaking

gigs because he had to, not because he was physiologically suited to tossing chunks of ore in gondolas

or whacking and sawing at redwood trees. He was a small man. As soon as he could, he developed skills in

carpentry and plumbing and whatever else he could parley into becoming a general contractor.

By combining their potential to earn income, Augusta and Fred had enough to make it possible for her

little sister Amanda to give up her job as a waitress at the Hammond Lumber Company cookhouse in

Samoa, the mill town on the other side of Humboldt Bay. The working conditions there were so exploitive

for the live-in staff of cooks and waitresses that being employed there was not just a physical ordeal,

it was soul-numbing. As soon as Augusta and Fred could manage to provide Amanda with lodging and a small

salary, they made the offer, and Amanda accepted. Amanda still worked as a waitress, but in small

restaurants in Augusta and Fred’s neighborhood for limited hours, meaning she was otherwise on-hand to be

Mildred’s nanny. Augusta could therefore accept the sort of lead-role wage-earning gigs that would

bring in enough compensation to genuinely get ahead of the game.

While Mildred was still an infant or at most a toddler, the Malms became the operators of Brooklyn House,

a boarding house in the 400 block of Third Street near the waterfront. It was Fred’s name on the contract,

but it was Augusta who shouldered much of the day-to-day work necessary to keep the place functioning, as

in the cooking, laundry, housekeeping, and so forth. Fred’s part was to take care of the physical repair

and maintenance -- doing so while continuing to nab temporary carpentry jobs wherever he could land ones

that would fit into other scheduled obligations. This part of Eureka was teeming with immense barracks

owned by the lumber companies and filled with hundreds of sawmill workers. Brooklyn House was a small-scale,

private operation -- an alternative for those bachelor laborers who had a little extra money to spend and

craved a less-institutional setting. The 1910 census shows that in the spring of that year, Augusta and

Fred were hosting only ten lodgers. Across the street was Sunnydale House, a similar facility operated by

Fred’s sister-in-law Tilda, with Victor Malm functioning as her “repair and maintenance guy” according to

the same style of partnership that Augusta and Fred were observing.

In the spring of 1911, Victor and Tilda’s son Harold died at no more than a year of age. Fred and Victor’s

parents back in Finland had never had the opportunity to meet the boy, who was their very first grandchild.

Soon Tilda became pregnant a second time, and the couple decided they would spend the winter season back

in the old country so that when the birth occurred, the elderly couple would get to be part of the happy

occasion and would have at least a couple of months to get to know their new descendant. Victor and Tilda

followed through on that plan. They would return in 1912 with baby Vera in tow. Meanwhile Fred needed an extra

pair of hands to complete the various carpentry jobs he was undertaking, but things worked out because Axel

Smeds was Fred’s other helper, and he remained available.

Through the early 1910s, Fred became increasingly known as a trustworthy contractor and was obtaining better

and more profitable gigs. Needing to concentrate on doing those jobs well and on schedule, he and

Augusta gave up running Brooklyn House. By late 1911 or certainly by the beginning of 1912, Augusta became

a cook at a restaurant at 122 F Street, even nearer the waterfront. Her employers were a pair of female

proprietors, Miss Bertha Woge and a Mrs. Goldstein. The photograph above is of Augusta in her apron posing

with Amanda and Mildred in front of that restaurant. (The cat, alas, is unidentified.) Amanda is well

known to have topped out at only five foot two. Augusta, as you can see, was shorter still.

The Malms lived upstairs at 122 F Street during this interval, along with Amanda. Axel Smeds lived 128 F

Street, either in the same building or right next door. One reason for being based there, aside from

Augusta’s employment, was that Fred may have been hired to remodel the structure. The same live-near-the-work

factors may have been behind the subsequent move in either late 1912 or in early 1913 to 3024 Williams Street.

Again Axel was there, this time sharing the exact same address. Axel was however not able to put in a lot

of hours helping Fred because he had obtained a job as a deliveryman/driver for D.C. McDonald, a large

hardware wholesaler/retailer. Victor Malm was back, though. He and Tilda moved in next to Fred and Augusta

at 3012 Williams. One way or another Fred succeeded in fulfilling his various construction contracts.

Victor and Tilda lingered at 3012 Williams for years, but by 1914, Augusta and Fred moved on to 3314 K

Street, where they would remain for at least three years -- their longest tenure yet in the same dwelling.

This period corresponded to Mildred’s first years of school, and so it was a priority to stay put. The

fact that Mildred was now a schoolkid brought another transformation in that Amanda’s contribution as a

nanny was no longer essential. Amanda allowed this to influence her life choices. After a year sharing

quarters with Axel at 2410 Albee, Amanda accepted the proposal of Charles Strom, a native of a small

community near Soklot, and buddy of Axel and Billy. Amanda had first met Charlie face-to-face in 1907,

during the time she had been employed as a waitress at the Hammond Lumber Company cookhouse in Samoa,

but for one reason or another their romance had built slowly. Meanwhile Axel formalized his relationship

with his girlfriend Ina Marie Jacobsen, another immigrant from Ostrobothnia.

Augusta was delighted that her two youngest siblings were at last embarking on the founding of their own

families. Her joy, though, was tempered. No sooner had Amanda and Charlie’s wedding taken place in the

autumn of 1915 than the couple left Eureka for good, thus ending the day-to-day closeness the two sisters

had enjoyed for such a lengthy span. By this point Billy Smeds was a married family man living upon and

overseeing his own acreage north of Reedley adjacent to the parcel he had developed for Jack. Meanwhile

Jack and Annie had finally said good-by to San Francisco and had taken up residence on their farm. Amanda

and Charlie established a third farm a couple of miles east of where the two brothers were based. With

three siblings in the San Joaquin Valley and another in New Hampshire, Augusta was confronted by the

reality that she would not get to be a direct observer as the majority of her nephews and nieces grew up.

Understandably, she would go on to treasure the exceptions -- Axel’s sons Kelly and Howard. The way she

doted upon them would ultimately prove to be hugely important to both boys, because their mother was not

nearly as reliable a source of affection.

In 1917-18, even as America was embroiled in World War I and the nation was going through concomitant

upheaval, Fred succeeded in getting approval from the city to build an entire block-long sequence of

homes on L Street. Signing his name to the bank loan was of course a gamble, but he and Augusta had faith

they could make the project happen as long as they played it smart and were not subject to some sort of

unreasonable twist of fate. One measure

they took was to reduce their personal financial burden by moving into 2729 L Street, one of the first

if not the first of the houses Fred erected -- probably doing so even before the some of the

amenities and special touches were installed. That saved them the cost of the rent they had been paying

at 3314 K Street. Next Axel and Marie became the tenants of the house at 2719 L Street, meaning Fred and

Augusta had that flow of rental income right away, again for a structure that did not have to be made as

ready for occupation by Axel and Marie as it would have been necessary to do for members of the general

public. After that, the income from each completed house helped cover the costs of the next. What was needed

was for at least one or two houses to be sold rather than rented so as to provide a big boost of cash

to get Fred and Augusta securely ahead of the bank loan payments. Once that happened, the couple did

their best to hang on to a number of the properties. The city would soon expand in that direction and the

prices they could demand would increase handsomely. For at least a little while, during the closing months

of the war, even as people everywhere were soon to have to worry about the great flu pandemic, Fred

took a job in Samoa with Hammond Lumber Company as a ship carpenter, as did his brother (who was probably

a co-investor in the construction project). That was the nerve-wracking juncture in the process. Fortunately

the interval lasted no more than a year, and possibly only a matter of months, before it became clear

the great scheme was going to yield the reward Fred and Augusta had hoped for. In the long run, it

would bring in even more than expected.

In the meantime, in a non-financial way, the family suffered the opposite of good fortune. Though everyone

made it through the first winter of the pandemic (1918-1919) without casualties, Axel caught the virus toward

the end of the following winter. He died 13 March 1920. Augusta was thus deprived of the one sibling who had

remained within her sphere. Her grief was strongest when she viewed it through the lens of her poor nephews.

The youngest, Howard, was so little he would come of age with no surviving memories of his father. Augusta

and Fred agreed that they would try to provide for the youngsters in one of the key ways Axel would have done

if Axel had survived, which was to make sure Kelly and Howard had the advantage of steady circumstances. The

house at 2719 would remain the boys’ home until they were grown. It was not put on the market until the early

1940s, even though that was long after the other structures on L Street had been purchased. The Malms let

Marie stay put at a rent she could afford.

Axel and Ina Marie Smeds hosted a visit from Jack and Annie Smeds in late 1918 at their home at 2719 L

Street in Eureka, not long after the house was constructed. (At this point, of course, Augusta and Fred

and ten-year-old Mildred were residing right next door.) Lined up left to right (zoomed in on in the

view below) are: Mildred Augusta Malm, Lillian Anna Smeds, Axel Smeds, Ina Marie Jacobsen Smeds holding

infant Howard Jacob Smeds, small boys Clarence Axel “Kelly” Smeds and Lawrence Jakob Smeds, both seated

high up on a tall end table draped with a lace tablecloth, Jakob Herman “Jack” Smeds, Anna Gustava

Rautiainen Smeds, Isak Alfred “Fred” Malm, Augusta Sofia Smeds Malm, and Sylvia Alice Smeds.

Axel just missed out on seeing Augusta and Fred reap the big reward of the success of their real-estate

scheme. They purchased a two-hundred-acre dairy just south of Eureka, on the rural fringe of the small

community of Bucksport on the shore of Humboldt Bay where the Elk River emptied into it. The couple took

possession 9 July 1920. Over the decades to come the acreage would increase tremendously in value. The

city of Eureka expanded southward and absorbed Bucksport. Various homes and commercial buildings went up,

and there was the Malm property right there along the main highway -- known as Redwood Highway at first,

to be redesignated Highway 101 as the nation’s interstate highway system was created -- its seemingly

unexploited expanse tempting would-be developers. But Augusta and Fred ignored that pressure and used the

property for what it was when they acquired it, as a dairy. This was not obstinacy on their part. The

flatlands of Humboldt County were perfect for dairy production. The business thrived. They kept the

parcel in a rural condition aside from the milk parlor, bottling plant, and of course, their house.

In a way it was ironic -- two of Augusta’s brothers and one of her sisters had moved hundreds of miles

from Eureka so that they could be farmers, and yet Augusta was now mistress of a farm larger in

physical dimensions than all three of theirs put together.

Augusta and Fred had secured themselves financially, for the future as well as for the moment. That was

in itself a cause for celebration, but the situation also meant they could attend to their other,

long-postponed goal: to have a larger family. By the time they acquired the deed to the dairy that July

day of 1920, Augusta was already pregnant. She was thirty-seven, going on thirty-eight. The couple did

not want to delay because they had in mind to have multiple additional children. As they moved into their

new home, getting the nursery area ready was among the things they paid attention to. In due course, the

anticipated happy occasion arrived. Except it was not a happy occasion. Augusta gave birth 15 February

1921 to daughter Alice M. Malm, but the baby died the same day. Augusta and Fred mourned almost a year

before trying again. Unfortunately this pregnancy came

to a similar culmination. Another girl was born 5 October 1923. Like her sister, she was not stillborn,

but she did not last out the day. As far as is known, she was never given a name. Together these two Malm

girls were the last of their generation, the sixteenth and seventeenth grandchildren

of Herman Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs. They were the third and fourth of that group to perish,

and the only ones whose lives went into the record measured in hours rather than months or years. Augusta

was not quite forty-one when the second tragedy took place, but there is no indication she and Fred tried

again. They had experienced enough heartache. They accepted that Mildred would be the only child they would

have the pleasure of raising to adulthood. Thankfully Mildred was healthy. She would in fact go on to reach

more than ninety years of age.

As the years went on, the dairy prospered. While it had probably been the plan for Augusta to play a

limited role in its management, at least during the early 1920s when she had expected to be chasing around

after young children, she instead dived right in and was without doubt a direct contributor to its success.

There were various ways this success manifested. Those of us alive today in the Twenty-First Century still

understand that milk has commercial value, but we are less aware of how paramount a commodity it was in the

early Twentieth. Householders had grown up milking cows of their own in barns and sheds right next to their

houses. They had not yet lost the habit of consuming large amounts of milk, cream, and butter each and

every day. Furthermore they wanted it fresh, and vast refrigerated-distribution networks had not yet

been developed. Malm’s Dairy was literally the closest source of fresh milk for much of Eureka, and had the

capacity to supply a great deal of the amount needed. Hundreds of Eureka housewives went to their back

porch steps each morning and brought in a jug or two of milk that a Malm’s Dairy deliveryman had dropped off

some time before dawn. Fred and Augusta built up their herd to the maximum their facility could handle,

leasing three separate parcels of land south of the city to grow enough feed for that many animals. They

put in a large, state-of-the-art bottling plant, capable of so much production a local brewing company

contracted with Malm’s Dairy to do the bottling of their beverages.

Even the relatives back in Finland came to know of Malm’s Dairy. And so did those in New Hampshire. When

Walter Johnson, the teenaged son of her sister Mary, wanted to know if there might be a job for him and

a buddy if they came out west, Augusta encouraged him. Accordingly, as soon as Walter graduated from high

school in June, 1928, he and his good friend Lawrence Holt spent every spare minute of the summer

restoring a 1919 Ford convertible and carefully planning their cross-country jaunt. They could barely

afford to go. They managed the expense by almost completely avoiding motels and hotels, sleeping in their

tent or in or beneath the car instead. They fixed their own meals rather than eat in restaurants, even

when lack of a campfire meant consuming everything cold. With all those measures, they kept the entire-trip

cost down to $172.00, as documented in the log Walter maintained. That was a whopper of a figure by their

standards, but they had been prepared for even worse. As it was, they even managed to make a few detours

and get to see for themselves such renowned sights as Niagara Falls and Yellowstone Park. The pair left

New Hampshire on the morning of 20 August 1928 and arrived at Malm’s Dairy at six in the evening of

September 15th, having set out that day well before dawn from The Dalles, Oregon and making a final

549-mile sprint to their destination.

Augusta and Fred made the newcomers feel so completely welcome both remained for over four years, if not

longer, living and working right at the dairy as bottlers. Lawrence Holt liked Eureka so much he lived

out his life there, owning and operating a cigar-and-newsstand store for many decades. The affection and

accommodation extended by his aunt and her husband meant the world to Walter. He had multiple reasons for

wanting to abandon his hometown of Berlin, NH. It was an isolated and provincial sort of place, a company

town where pretty much everybody worked for the big paper mill, The Brown Company, or they didn’t work at

all. The weather was cold and so was Walter’s father’s demeanor. And then there was the gossip. It seems

obvious from the perspective of today that Walter and Lawrence were more than just buddies, more than just

high-school pals who had enjoyed being involved in Berlin High School’s stage plays and musical productions

together. In Augusta and Fred’s home, Walter found the warmth and acceptance he had been denied at home.

Walter might well have worked his way up to becoming Fred’s right-hand man and one of the heirs of the

business if he’d dedicated himself to it. However, that role was a natural fit for a son-in-law, and in

the fullness of time, a son-in-law appeared. He was Paul Joseph Lieber of Michigan. In late 1930 or in

1931 he came to Eureka, where one of his long-time friends had recently been hired as a pharmacist.

Mildred was twenty-two or perhaps even already twenty-three when she and Paul first encountered one

another. She was old enough to know what she wanted, and she wanted him. The pair were wed in the spring

of 1932.

The wedding was scarcely out of the way when Augusta and Fred

completed one of the entrepreneurial

developments they had been working toward for quite some time. In those days when the nation was still

mired in the worst of the Great Depression, proprietors knew not to coast on their laurels if they

wanted their enterprises to remain viable. For a number of years, there had been a gradual winnowing

of the doorstep-delivery side of the dairy’s business. By 1932, most householders had ice boxes or even real

refrigerators. They could buy milk on a spot-purchase basis, a quart or half-gallon at a time at stores

right in town rather than having Malm’s Dairy or one of its competitors bring it in from the rural parts

of Humboldt County by subscription in quantities beyond what was actually needed. Augusta and Fred

recognized the advantage of establishing their own retail store right where the customers were. The best

way to accomplish that was to buy a plot of city land and put up a building. They had the capital,

real-estate prices were very affordable due to the sluggish economy, and Fred possessed the expertise as

a contractor. The building, located at the corner of F Street and Randall, opened its doors at the

beginning of July, 1932. The Malm’s Dairy outlet took up only

part of the square footage. The rest was devoted to a Rite-Way store and a barbershop, meaning that even

if their operation proved marginal, the Malms would still make money via lease payments.

The wedding was scarcely out of the way when Augusta and Fred

completed one of the entrepreneurial

developments they had been working toward for quite some time. In those days when the nation was still

mired in the worst of the Great Depression, proprietors knew not to coast on their laurels if they

wanted their enterprises to remain viable. For a number of years, there had been a gradual winnowing

of the doorstep-delivery side of the dairy’s business. By 1932, most householders had ice boxes or even real

refrigerators. They could buy milk on a spot-purchase basis, a quart or half-gallon at a time at stores

right in town rather than having Malm’s Dairy or one of its competitors bring it in from the rural parts

of Humboldt County by subscription in quantities beyond what was actually needed. Augusta and Fred

recognized the advantage of establishing their own retail store right where the customers were. The best

way to accomplish that was to buy a plot of city land and put up a building. They had the capital,

real-estate prices were very affordable due to the sluggish economy, and Fred possessed the expertise as

a contractor. The building, located at the corner of F Street and Randall, opened its doors at the

beginning of July, 1932. The Malm’s Dairy outlet took up only

part of the square footage. The rest was devoted to a Rite-Way store and a barbershop, meaning that even

if their operation proved marginal, the Malms would still make money via lease payments.

Augusta and Fred had arrived at a point where it must have

seemed as though things couldn’t get any better. They were well-to-do. Business was good. And their little

girl was grown and married. Moreover, they were just fifty years old, with seemingly many years left

to enjoy all that they had. But that “many years” part was not what fate had in mind. Things took a turn

early in the morning of December ninth. It was Fred’s habit to rise before Augusta and as one

of his regular displays of affection, he would bring her coffee in bed. He left her as she was stirring

in her measure of sugar. Not long after he had returned to the kitchen, he heard the sound of her cup

shattering on the floor. He rushed back to the bedroom to discover she’d had a stroke. She was

admitted to St. Joseph Hospital, but she did not improve, and on the eleventh, she had another stroke.

It was fatal. At only fifty years old, her life was done. Her survivors were left reeling. They’d had

no warning. There had been no opportunity to anticipate the loss of their loved one and figure out how

they would cope with her absence. They just had to experience it full force. The year 1932 went down in

their memories as one of the bad ones.

To bear the loneliness, Fred asked his daughter and son-in-law to move in with him. They had been married

such a short time they had not yet purchased a home. They were still renters. They agreed to the

arrangement. At first, everyone viewed it as a temporary measure, lasting until some sort of natural

curtain call such as Paul being offered a job too good to be refused, or Fred marrying a new wife. But in

fact, Fred never remarried, and Mildred and Paul stayed for good, not only until the end of Fred’s life,

but until the end of Paul’s, and nearly to the end of Mildred’s, though Mildred had nearly seventy years

yet to live. Paul took on increasing responsibility at Malm’s Dairy. Another fringe benefit of the

cohabitation was that Fred was right on hand to enjoy seeing his grandchildren grow up. They consisted

of a granddaughter, Lynne Kay Lieber, born in 1936, and a grandson, Kyle Paul Lieber, born in 1941.

By the early 1940s, Fred was turning sixty, and was feeling his age. He had diabetes to contend with,

and though he had always maintained sensible, healthy habits, the decline was underway and would ultimately

keep him from becoming truly elderly. Recognizing his situation, he began scaling back his workload, and

off-loading assets he no longer had the energy to exploit. He sold the building at F Street and Randall,

as well as the bottling plant. Thereafter, he concentrated upon the core business. Malm’s Dairy continued

to be one of the mainstay, everyone-knows-the-name commercial ventures of Eureka -- a sponsor of local

youth sports teams, etc. Fred was able to retain an owner level of control even in the face of the trend

toward dairy mergers. He did not make the mistake of ignoring the advantages of some consolidation,

however. Larger inventory meant the ability to tap into better distribution and opened up greater chances

for customers to become acquainted with a given brand name. In 1941, Malm’s Dairy partnered up with Graham

Dairy and a small local conglomerate called Sanitary Dairies. Perhaps it was Fred who convinced his

partners that referring to something as sanitary begs anyone who hears it or sees it to then be unable to

get the impression of unsanitary out of their mind. The coalition settled upon the much better name,

Eureka Dairies. Even then, the name Malm’s Dairy was retained for certain uses. It was not until after

Fred’s death that Eureka Dairies was swallowed up by Humboldt Creamery Association, a consortium of some

four hundred dairies. The latter operation, which issues products under the Challenge brand, still exists.

Challenge butter, cream, and milk are to be found in dairy cases throughout northern California.

As he approached and then surpassed seventy years of age, Fred’s health deteriorated in a more profound

way. After showing ample signs the end was drawing near, he finally passed away in a Eureka hospital 26

December 1953. Three days later, his remains were buried beside those of Augusta in Sunset Memorial Park.

The gravesite, which features a panoramic view of Humboldt Bay, was not Augusta’s original resting place,

as the cemetery was not established until four years after her death. Her reburial at Sunset was almost

a case of coming home. The very next parcel south of the cemetery, sharing a boundary with it, was Augusta

and Fred’s dairy farm.

Augusta Sofia Smeds and Isak Alfred Malm. Their wedding portrait.

Children of Augusta Sofia Smeds

with Isak Alfred Malm

Mildred Augusta

Malm

Alice M.

Malm

Baby Girl

Malm

To return to the Smeds Family History main page, click here.

Augusta Sofia Smeds, second child and eldest daughter

of Jakob Herman Mattsson Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs, was born 9 November 1882 on the

ancestral Smeds estate in Soklot in the parish of Nykarleby, Finland, a place that would continue

to be her home throughout her childhood, as it had been home to many generations of Smedses. She

was nicknamed Gusta, though nearly all surviving records refer to her by her formal name.

Augusta Sofia Smeds, second child and eldest daughter

of Jakob Herman Mattsson Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs, was born 9 November 1882 on the

ancestral Smeds estate in Soklot in the parish of Nykarleby, Finland, a place that would continue

to be her home throughout her childhood, as it had been home to many generations of Smedses. She

was nicknamed Gusta, though nearly all surviving records refer to her by her formal name.

Fred (shown left) had left behind much of his family in

the mother country, but not quite all -- his slightly younger brother Victor (full name Johan Victor

Isaksson Malm, which was Americanized to John Victor Malm) also came to live in Eureka, and in

decades to come Fred would be uncle to a niece, Vera, and a nephew, Shirley (aka Oliver). (Another

nephew, Victor Harold Malm, died in infancy.) The Malm brothers may have been part of the well-known

Malm clan of Vasa province. That clan had grown rich in the 1700s and early 1800s as owners of a major

commercial empire based upon shipbuilding. As described in Augusta’s father’s biography, Ostrobothnia

was the place to build ships during that era. Alas, Finland had lost its dominance in the

industry because no matter how well-suited the region had been for the construction of vessels made

of wood and tar, it enjoyed no advantage at all once shipbuilding came to depend upon steel. Fred and

his brother apparently were not the beneficiaries of a trove of legacy wealth. This appears to have

been a sore point. The brothers’ endowment was so paltry they were essentially compelled to emigrate so

that their shares of their birthright could go to their younger sister Emilia Adelina, who stayed in

Finland lifelong. Fred remained so bitter about being “sent into exile” he would only communicate in

English, refusing to fall back on Swedish even when among other immigrants who loved to chat in their

mother tongue when possible. However, it is fair to say the fact that some of his recent forebears

had enjoyed privileged lives spurred him to improve his own circumstances -- and by extension improve

Augusta’s circumstances. Moreover, he “thought like a rich man.” That is to say, he devoted himself

to finding ways to use capital and investments to make money, not just to earn income entirely through

personal labor and wages.

Fred (shown left) had left behind much of his family in

the mother country, but not quite all -- his slightly younger brother Victor (full name Johan Victor

Isaksson Malm, which was Americanized to John Victor Malm) also came to live in Eureka, and in

decades to come Fred would be uncle to a niece, Vera, and a nephew, Shirley (aka Oliver). (Another

nephew, Victor Harold Malm, died in infancy.) The Malm brothers may have been part of the well-known

Malm clan of Vasa province. That clan had grown rich in the 1700s and early 1800s as owners of a major

commercial empire based upon shipbuilding. As described in Augusta’s father’s biography, Ostrobothnia

was the place to build ships during that era. Alas, Finland had lost its dominance in the

industry because no matter how well-suited the region had been for the construction of vessels made

of wood and tar, it enjoyed no advantage at all once shipbuilding came to depend upon steel. Fred and

his brother apparently were not the beneficiaries of a trove of legacy wealth. This appears to have

been a sore point. The brothers’ endowment was so paltry they were essentially compelled to emigrate so

that their shares of their birthright could go to their younger sister Emilia Adelina, who stayed in

Finland lifelong. Fred remained so bitter about being “sent into exile” he would only communicate in

English, refusing to fall back on Swedish even when among other immigrants who loved to chat in their

mother tongue when possible. However, it is fair to say the fact that some of his recent forebears

had enjoyed privileged lives spurred him to improve his own circumstances -- and by extension improve

Augusta’s circumstances. Moreover, he “thought like a rich man.” That is to say, he devoted himself

to finding ways to use capital and investments to make money, not just to earn income entirely through

personal labor and wages. She would only get to have her father near at hand

for less than a complete calendar year. At the end of 1907, he and Billy left Eureka for good,

proceeding down to Fresno County to take up active management of the farm Jack had purchased north of

the small town of Reedley, but which Jack could not personally oversee because needed to stay put and

hold on to his good-paying job at Shreve & Company. Augusta was undoubtedly wistful at the absence of

these loved ones, but the fact is, she was far too busy to dwell upon the circumstance. For one thing,

she was reaching the end of her first pregnancy. Daughter Mildred Augusta Malm was born in the middle

of March, 1908. (Shown at right, Augusta and Mildred. There was no date written on the original

photograph, but judging by Mildred’s apparent age it would seem to have been taken in 1910 or 1911.)

She would only get to have her father near at hand

for less than a complete calendar year. At the end of 1907, he and Billy left Eureka for good,

proceeding down to Fresno County to take up active management of the farm Jack had purchased north of

the small town of Reedley, but which Jack could not personally oversee because needed to stay put and

hold on to his good-paying job at Shreve & Company. Augusta was undoubtedly wistful at the absence of

these loved ones, but the fact is, she was far too busy to dwell upon the circumstance. For one thing,

she was reaching the end of her first pregnancy. Daughter Mildred Augusta Malm was born in the middle

of March, 1908. (Shown at right, Augusta and Mildred. There was no date written on the original

photograph, but judging by Mildred’s apparent age it would seem to have been taken in 1910 or 1911.)

The wedding was scarcely out of the way when Augusta and Fred

completed one of the entrepreneurial

developments they had been working toward for quite some time. In those days when the nation was still

mired in the worst of the Great Depression, proprietors knew not to coast on their laurels if they

wanted their enterprises to remain viable. For a number of years, there had been a gradual winnowing

of the doorstep-delivery side of the dairy’s business. By 1932, most householders had ice boxes or even real

refrigerators. They could buy milk on a spot-purchase basis, a quart or half-gallon at a time at stores

right in town rather than having Malm’s Dairy or one of its competitors bring it in from the rural parts

of Humboldt County by subscription in quantities beyond what was actually needed. Augusta and Fred

recognized the advantage of establishing their own retail store right where the customers were. The best

way to accomplish that was to buy a plot of city land and put up a building. They had the capital,

real-estate prices were very affordable due to the sluggish economy, and Fred possessed the expertise as

a contractor. The building, located at the corner of F Street and Randall, opened its doors at the

beginning of July, 1932. The Malm’s Dairy outlet took up only

part of the square footage. The rest was devoted to a Rite-Way store and a barbershop, meaning that even

if their operation proved marginal, the Malms would still make money via lease payments.

The wedding was scarcely out of the way when Augusta and Fred

completed one of the entrepreneurial

developments they had been working toward for quite some time. In those days when the nation was still

mired in the worst of the Great Depression, proprietors knew not to coast on their laurels if they

wanted their enterprises to remain viable. For a number of years, there had been a gradual winnowing

of the doorstep-delivery side of the dairy’s business. By 1932, most householders had ice boxes or even real

refrigerators. They could buy milk on a spot-purchase basis, a quart or half-gallon at a time at stores

right in town rather than having Malm’s Dairy or one of its competitors bring it in from the rural parts

of Humboldt County by subscription in quantities beyond what was actually needed. Augusta and Fred

recognized the advantage of establishing their own retail store right where the customers were. The best

way to accomplish that was to buy a plot of city land and put up a building. They had the capital,

real-estate prices were very affordable due to the sluggish economy, and Fred possessed the expertise as

a contractor. The building, located at the corner of F Street and Randall, opened its doors at the

beginning of July, 1932. The Malm’s Dairy outlet took up only

part of the square footage. The rest was devoted to a Rite-Way store and a barbershop, meaning that even

if their operation proved marginal, the Malms would still make money via lease payments.