The Ancestry of Hannah Strader

Hannah Strader’s lineage is known back to the ancestors

who came to the Colony of North Carolina about 1750. There is so much to say, in fact, that this is

the most text-heavy of all the individual pages of the Nathaniel Martin/Hannah Strader

website. Keep in mind that even though a great deal is mentioned here, this is still only a summary.

Hannah Strader’s lineage is known back to the ancestors

who came to the Colony of North Carolina about 1750. There is so much to say, in fact, that this is

the most text-heavy of all the individual pages of the Nathaniel Martin/Hannah Strader

website. Keep in mind that even though a great deal is mentioned here, this is still only a summary.

Much of the knowledge cited here comes as a result of the genealogical research

of Howard Frame in the 1960s and early 1970s. Howard was descended from Elizabeth Strader, a

sister of Hannah, who married Jeremiah Frame. The union of Jeremiah and Elizabeth was one of at

least six Strader/Frame marriages, entwining the clans to such a degree that the Strader

story was a natural focus of Howard’s investigations. Though Howard labored without

the advantages of the internet era, he succeeded in finding enough documentation to pencil in a

sketch of the family in early America. He found that Hannah’s bloodlines were thoroughly

German, most or all of them qualifying as “Pennsylvania Dutch.”

The easiest way to structure a discussion of Hannah’s forebears is to to begin with the

most ancient known and proceed chronologically. Below you will find three sections of text, each

launching with one of three immigrant ancestors -- Johann Heinrich Strader, John Jacob

Starr, or Heinrich Weitzel -- and proceeding down to Hannah. But first, it is useful to talk

about the Pennsylvania Dutch migration in general.

The story begins in a region of Germany known as the Palatinate. This area, part of the Rhineland,

lies just north of the Alsace-Lorraine region and up against the eastern borders of Luxembourg and

Belgium. By the early 1700s this area was home to a population divided into three major sects of

Christianity -- Lutheran, Calvinist, and Catholic. This division of power meant each group dreamed

of becoming dominant, and no lasting stability could be counted on until such time as that happened.

The prize was obvious. With the retreat of the plague years the land, a wonderfully

fertile agricultural zone, had become prosperous. Among those who coveted it were outsiders, hoping

to further their own interests by shifting the balance of control one way or another. The most

infamous meddler was the French monarch Louis XIV, the famous “Sun King.” During his tremendously

long reign (1643-1715) he repeatedly sent his armies over the border, ostensibly to support his

Catholic brethren, but also for purposes of pillage. A crisis developed following

a somewhat pointless invasion in 1707, a campaign apparently fueled by the ambitions of one of

Louis’s field marshalls rather than by the king himself. The invaders withdrew almost at once. Some

say that during the retreat of the French forces, the marshall gave the residents three days to

flee, and then the army destroyed everything on their way home, a “scorched earth” military tactic.

It is said that the fleeing people gathered eventually into refugee populations that had to fit

themselves into the societies of neighboring countries. More objective histories say that the

residents did not actually have to leave, but in the wake of an intensely cold winter of 1708-09

that destroyed orchards and vineyards that had stood for generations, the prospect of starting

over elsewhere did not seem so daunting given that the families were going to have to replant

fields and rebuild homes and barns and shops anyway. Moreover, even in peaceful times the

Palatinate was too crowded, leaving few opportunities for the younger generations of

agricultural families to obtain acreage sufficient to support a household. Soon pamphlets extolling

the virtues of the colonies of Pennsylvania and North Carolina began circulating in editions in the

tens of thousands of copies. Queen Anne of England, eager to help what she perceived as victims of

religious persecution, and Parliament, eager to fill the American possessions with white, Protestant

settlers but not wanting to deplete England to do so, approved a policy in 1709 that

granted free passage to any “citizens of foreign nations” that wished to settle there, provided

they swore allegiance to the Colonies when they arrived. Some, particularly a large surge of

Lutherans, immediately took advantage of this offer. From 1709 through the early 1750s, as the queen

continued to subsidize the voyages, many more followed, and the phenomenon began to draw more and

more Germans from beyond the Palatinate as well.

One of the key groups in this mass exodus consisted of families who had at first sought asylum

in the Netherlands. Perhaps some of them were biding their time hoping for the opportunity to

reclaim their homes in Germany, but political unrest prevailed in the France/Germany border

area for the remainder of the century. Eventually these families crossed the Atlantic. However,

having spent as much as thirty or forty years in Holland, they had become “Dutchified” in speech

and customs. As these later refugees crossed the Atlantic, many landed in Philadelphia and settled

in eastern Pennsylvania. This is the group famous today as the “Pennsylvania Dutch.” Hannah’s

forebears have been described as such here; however, strictly speaking the label only lightly

applies, because the relevant individuals spent at most a dozen years, and some probably only

a matter of weeks, within the bounds of Pennsylvania.

Hannah’s ancestors may well have rejected Pennsylvania as a long-term home because they were of

somewhat different character than their co-travellers. Many of the latter, thanks to the decades

spent in the Netherlands, had shifted their Lutheran or German Reformed religious affiliation to the

Dutch Reformed Church. Hannah’s people had resisted this change. The sub-group naturally felt more

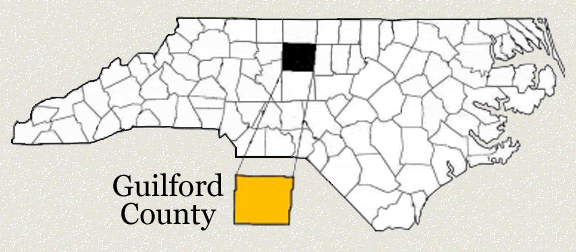

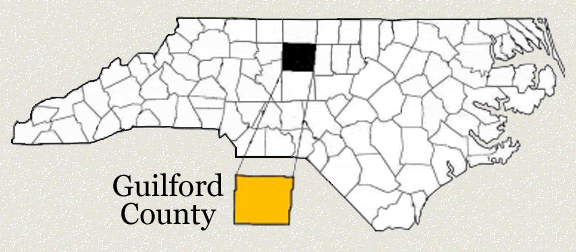

comfortable cleaving to others like themselves, and one of the places they chose to gather was Guilford

County, NC, where they were better able to preserve their way of life with less pressure to assimilate.

Becoming speakers of English and having to use Anglicized versions of their names already represented

a sea change in their identities; they didn’t want to give up all they had stood for. So down the

famous Emigrant Trail came Johann Heinrich Strader, John Jacob Starr, and Heinrich Weitzel and the

women who were, or soon would be, their wives.

Johann Heinrich Strader

Johann Heinrich Strader was a great great grandfather of Hannah. He is one of only two of that

generation that has so far been identified by name, the other one being his son Henry’s

father-in-law Nicholas Holstein. The rest of the immigrants who will be discussed below, including

John Jacob Starr and Heinrich Weitzel, were one generation more recent -- great grandparents of Hannah.

Johann Heinrich was probably born in the early 1720s, though this is only an estimate. His

birthplace was probably the Netherlands because he used Johann (sometimes rendered as Johannes) rather

than Hans -- Hans being a “more German” variation of the name, which in English would be rendered as

John, Jack, or Johnny. Having this first name does not

mean he went by Johann, though. Many Palatinate households used naming traditions as an expression

of religious faith. The name honors John the Baptist and/or the Apostle John. The practice was so

common that -- as will be discussed below in the section dealing with John Jacob Starr -- the same

immediate family might contain more than one son with the first name Hans/Johann/Johannes/John. You

might think this would lead to confusion, but in that time and place, there was no problem, because

the person would be identified by his middle name. The same phenomenon occurred with girl children named after

the Virgin Mary. Sisters living in the same home might be named Maria Sofia, Maria Katarina, and

Maria Anna. They would be called Sofia, Katarina, and Anna by everyone they knew. They would

be expected to use the first name only on extremely formal occasions. This has bearing on genealogical

research because the “formal occasions” protocol was often applied in cases of marriage records,

censuses, deeds, and ships’ passenger lists.

The name Johann Heinrich Strader (rendered as Johann Henrich Ströder) appears on the ship

captain’s list of the Ranier, sailing out of Rotterdam and arriving in Philadelphia on 26

September 1749. The same day, a “John Henry Streader” is listed as having made his oath of

allegiance to the Colonies. The ship’s captain’s list also includes a Casper Streader

and a “Johannes Ströder junge” or Johann Jr.

It seems probable that Johann Heinrich Strader of the Ranier is the same man who was

Hannah’s great great grandfather, and that “Junior” was his son, who will henceforth be referred

to in this essay as Henry Strader. If so, it would make sense that Henry was a child at the time,

but the Ranier information does indicate that Junior signed his name, which implies he was old

enough to write. The two Johanns might have been cousins or even brothers, or an uncle and nephew;

the repetition of Johann as a first name doesn’t preclude any of these possibilities.

It is also possible there was some sort of relationship to Casper Streader. People

with names that are the same phonetically, travelling on the same voyage of the same ship? It is

tempting to connect those dots. However, no other evidence links Casper and Johann Heinrich. A

Casper Stratter of Alsace Township, Pennsylvania -- very likely to be the Casper Streader who

came on the Ranier -- left a will dated 1778 whose text survives, and that text makes no

mention of Johann Heinrich or of any relatives living in North Carolina, where Johann

Heinrich settled.

Deeds and other records from Guilford County establish that a Johann Heinrich Strader was living

there from about 1750 onward. Whether this was the individual who sailed on the Ranier in 1849

has yet to be conclusively proven, but if “our” Johann Heinrich did not come on that particular ship,

he came on one much like it, and was then part of a large migration of people like himself southward

from Pennsylvania. It is generally known that Palatinate families with the surnames Albright, Clapp, Faust,

Holt, Sharp (Scherb), Cortner (Goertner), Ingold, Brower, Keim, Staley, May, Amick (Ewigs), Smith,

Stack, Nease, Ingles, Leinberger, Strader, and Wyrick established a colony of their folk in the

period between 1745 and 1760 in the counties of Alamance, Granville, Guilford, Orange, and Caswell,

NC. These were families who had kept to the German Reformed and Lutheran sects. Where genealogical

uncertainty arises is in which deeds, tax lists, and church records refer to Johann Heinrich, and which

refer to his son. On this webpage, the father and son pair are called Johann Heinrich and Henry for

ease of identification, but in the records from the 1700s North Carolina, they would both have been

Henry Strader -- Strader being rendered phonetically in most cases, by clerks who had to decide

on the spot what spelling to use, clerks who perhaps were not entirely literate themselves. And to

complicate matters further, spelling was not a standarized sort of thing in the first place in those

pre-Noah Webster days.

When Johann Heinrich died is conjecture, because it is so impossible to distinguish him from his

son in the extant records. We will leave that as a mystery and discuss Henry, the son, because

some of the documentation from the later decades of the 1700s unquestionably refers to him and not

to his father. Among those documents are various Granville County, NC court records. These

include: 1) The will of John Holstein, dated May 1790, which granted “to brother-in-law Henry Streider

land in Granville on Adock Creek.” Henry is also mentioned as one of two executors of that will, the

other being Jacob Holstein, a brother of the author of the will. 2) A wedding record that links Henry

Straiter (yet another spelling) to Catherine Holstein and gives a wedding date of 31 May 1773. John,

Jacob, and Catherine Holstein were likely three of the children of one Nicholas Holstein (Hostine),

whose own will is recorded in Granville County.

Neither Henry Strader nor Catherine Holstein were mentioned by name in the within-the-family

records that survived into the 20th Century. Those records begin with the family Bible of Henry’s

grandson, Jacob Strader, whose contents do not include details on Henry’s generation. The earliest

forebears in that source are Daniel Strader -- son of Henry and father of Jacob -- and his

wife, Elizabeth Wensck. However, public-source records establish that Henry and Catherine did exist,

and they dwelled in the right place and right time -- and obviously had the right surname -- to have

been Daniel’s parents. Henry and Catherine definitely had a son named Daniel, and only the strictest

of genealogists would argue that it might be some other Daniel than the one who was Hannah’s grandfather.

In addition to Daniel, the names of three other children of Henry and Catherine have surfaced. Those three

were Henry, Adam, and Katy, with Daniel falling between Adam and Katy in the birth sequence. Three

other children, all younger, are listed in the 1790 census, but their names are not mentioned in

that source, only their genders (a girl then a boy then another girl) and age ranges. Henry was the eldest,

born in 1774. More children may have been born after 1790.

One date mentioned for Henry’s death is 1792, but this does not agree with land transaction

records. Again, the possible confusion with other Henry Straders is a factor, but it seems likely

the “right” Henry bought and sold Orange County, NC land between 1787 and 1801, one tract deeded to Jacob

Holstein in 1787 and another tract to his son Henry in 1794. The place of death for both Henry

and Catherine is also unclear. By the end of their lives, a new migration had begun. North Carolina was

now the “old country.” The “land of promise,” now that the Indian tribes were being pushed out of the

region beyond the Appalachians, was Ohio. Henry and Catherine may have been content with the homes they

had founded when young, and/or they may have died before the uprooting began. Their son Daniel, however,

heeded the call westward.

Daniel’s life is firmly documented, and so we know his birth occurred 7 April 1777 in Guilford County.

He was raised there as well. Six days after he turned twenty-one (i.e. 13 April 1798), he married

Elizabeth Wensck, who had been born 22 August 1776, also in Guilford County. The bondsmen mentioned

in the county marriage records is George Strader (rendered as George Steador), who was probably

Daniel’s first cousin, son of the George Strader who fought in the Revolutionary War.

The first of Daniel and Elizabeth’s children, Jacob, was born 26 February 1799, about ten months after

the wedding. Daniel and Elizabeth would go on to have many more offspring. The names of eleven children

have surfaced. This may not be the full count, because these eleven names refer to children who reached

adulthood. There may have been others who perished in infancy or in early childhood whose identities have

been lost. Eleven may also be one too many names (see below).

Daniel and Elizabeth left North Carolina some time after the birth of their first four children -- Jacob,

Polly, Susannah, and Mary, the latter born in 1804. Later census records of relatives hint that perhaps

the family went next to Kentucky, but if so, it was a stopover of at most two or three years. Then

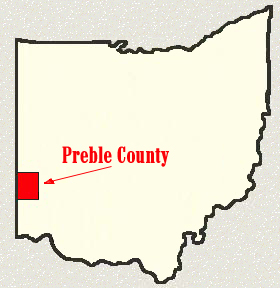

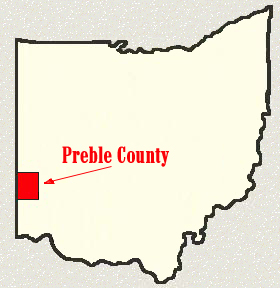

it was on to Preble County, OH. According to the reference work History of Preble County, Ohio,

1798-1881, Daniel and Elizabeth arrived in 1809, but this does not agree with birth information

concerning fifth child, named Elizabeth after her mother. She was born 25 March 1808 and her

birthplace is listed as Preble County in a number of sources. Most likely the family had reached

Ohio by the end of 1807. Their precise living place for the first few years -- during which time

sixth and seventh children Daniel Jr. and Rosannah came into the world -- is unknown, but a county

property transaction record reveals that Daniel purchased approximately 170 acres of land on 26 March

1813 from a Henry Strader -- this Henry probably being Daniel’s brother. The parcel, consisting of

“the West half of fractional Section of No. 18 Town 8 Range 2 East,” was home to Daniel and Elizabeth

for the rest of their long lives.

Daniel did not get to enjoy the experience of caring for and harvesting

the first crop off his

new land, though, because he left to fight in the War of 1812. The roll of Captain David E. Hendrick’s

Company shows Daniel as serving May 1 to November 18, 1813. He had put in a tour of duty the previous

year as well, and appears on the Roster of Ohio Soldiers of 1812, along with three other Straders.

Daniel did not get to enjoy the experience of caring for and harvesting

the first crop off his

new land, though, because he left to fight in the War of 1812. The roll of Captain David E. Hendrick’s

Company shows Daniel as serving May 1 to November 18, 1813. He had put in a tour of duty the previous

year as well, and appears on the Roster of Ohio Soldiers of 1812, along with three other Straders.

Daniel survived the war and spent the next forty years as a leading citizen and prominent landowner

of Preble County. The final four children, William, John, Levi, and Jane, were born by 1820 or not

long after. The majority of the eleven kids lived in Preble County lifelong. Most were still local

residents when Daniel passed away 11 February 1853. Elizabeth survived him only a brief while,

expiring 30 August 1855. Husband and wife were both laid to rest in the Sherer Cemetery, Washington

Township, Preble County. Sherer Cemetery had been established as a private graveyard of the Sherer

family and then was expanded to include neighbors and in-laws. Two of Daniel and Elizabeth’s daughters

had married Sherer men.

One of those Sherer/Strader marriages was that of Levi Sherer and Jane Strader. The best

public-source evidence of the composition of the Daniel Strader/Elizabeth Wensck family happens to

take the form of the records of the suit filed by Levi and Jane to force a partition of the

family estate, described as 167 acres, so that the various heirs or their descendants would be able

to get either get their fair share of the money or be able to obtain separate deeds to portions of

the acreage, according to their wishes. Jane was the youngest daughter, and no doubt a suit was the

only way she could get contrary older siblings to do right by her.

One puzzle brought up by the text of Levi and Jane’s petition is its reference to William Strader.

This child of Daniel and Elizabeth does not appear in any other source. The most logical explanation

is that William was an alternate name for John, who is known from other sources, and whose

name does not appear in the petition. This would mean there were only ten known children of

Daniel and Elizabeth, not eleven.

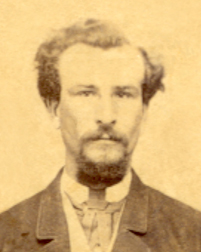

As mentioned, Daniel and Elizabeth’s eldest child was Jacob Strader, born in Guilford County before the

migration, then raised in Preble County from the age of seven or eight onward. He would eventually

become Hannah’s father. The first major step toward that development came with his marriage to Rachel

Starr, daughter of John Starr and Catharine Weitzel. The wedding occurred 1 October 1818 in Preble

County. Groom and bride were both eighteen years old and therefore had

many decades together to look forward to. Before discussing length and breadth of that union, let’s

shift back to the days when Guilford County was first being populated with its Palatinate settlers, and

describe the lives of the grandparents and parents of Rachel Starr.

John Jacob Starr

This individual’s life and identity are sketchy. His sons Adam, Jacob, and John -- all of whom

married women of the same Weitzel family in Guilford County, must have had a father. The naming conventions

of Palatinate families and the continuing use of the name Jacob in subsequent generations gives us the

name John Jacob Starr by inference. The actual form of his name used in source material ranges from

John Jacob to Jacob Starr to John Jacob Stohr -- Stohr probably being the “correct,” non-Americanized

version of the surname.

John Jacob Starr’s father may have been Johannes Starr, age 38, a man who arrived 16 September 1738

in Philadelphia aboard the ship Elizabeth, which had sailed from Rotterdam via Deal, England.

The passenger manifest of heads-of-families includes Johannes as well as three heads of Weitzel

families -- Johann Werner Weitzel (or Weinard Weisell, age 27), Martin Weizel (or Weisell, age 30),

and Henrich Weutsel (or Weitzel or Weisell, age 38). This is persuasive documentation that Johannes

Starr might be the patriarch of the Starrs who settled in Guilford County, because these subsequent

Starrs maintained a close association with the Weitzel clan. If the theory is correct, then Johannes was

among the group of Palatinate German immigrants who stayed in the area of Berks, Lebanon, Schuylkill,

or Lancaster Counties in Pennsylvania until about 1750, then travelled down the Emigrant Trail to

North Carolina. However, whether Johannes personally made it to that destination is unknown. His

name does not appear in North Carolina court records. Perhaps he was dead by 1750. Perhaps he stayed

in Pennsylvania. Given the uncertainties, Johannes is regarded as a “maybe” ancestor at this time.

As for “definite” ancestors, the best available within-the-family source for the history of the Starr

family is the material written by his great great granddaughter Mary Rachel Frame Webb, whom we will

call “Rachel Webb” (the name she went by at the end of her life, Webb being the surname of her final

husband) from here to the end of this document. Unfortunately, her account is not particularly

reliable in the matter of John Jacob Starr. In fact, it serves to confuse matters. Rachel Webb

states that Rachel Starr’s maternal grandmother -- this would be Anna Margaret Low, wife of John

Jacob Starr -- arrived in America from Germany as a widow with four boys, landing at

Baltimore. This would mean John Jacob Starr died young. This scenario does not agree with the timing of the

children’s birthdates. An early death also contradicts a theory in the volume Fox Family History

1703-1976 by John F. Vallentine, a reference work that touches repeatedly upon Hannah’s Guilford

County forebears and was used as a guide by Howard Frame in his research. This book points to a record

of the baptism of Adam Starr’s son John Jacob Starr, performed at the Brick Reformed Church in

approximately 1779. The baby’s “sponsors” were his grandparents John Jacob Starr and Anna Margaret Starr.

This implies John Jacob was in attendance to participate in the baptism of his grandson, and therefore

was alive in 1779. However, it is also possible the sponsorship was honorary, a token of respect for a

deceased family patriarch.

Boiling down the available references gives us a birthdate for John Jacob at the end of the 1720s,

probably in Germany rather than the Netherlands. Both he and Anna Margaret Low, who is believed to

have been born in about 1731, came to North Carolina well before 1750, perhaps with the first influx

of their people from Pennsylvania to Guilford County, which dates from 1744. Their wedding must have

occurred in 1749, about a year before the birth of their first child, Adam. These nuptials probably

took place in Guilford County. Altogether five children are known, the youngest born about 1760. Those

five were John Adam Starr (known as Adam), Jacob Starr, John Starr (known as John), Barbara Starr, and

Anna Maria Starr.

You will note that these five include only three boys, not the “four boys” referred to by

Rachel Webb. Webb also stated that the “widow” caused two of her sons to learn the tailor

trade, and two the blacksmith trade. This much may have been somewhat accurate. John Starr

is known to have been a tailor.

These three Starr brothers came of age in North Carolina and appear to have played a meaningful

role in their communities as young men, and are mentioned in various local records of the 1770s through

the early 1800s. In genealogical terms their most noteworthy

accomplishment was that they all, as mentioned above, married daughters of the same family, named

Weitzel. (1) Adam Starr married Margaret Weitzel. They had at least eleven children. Many of this brood

would be part of the migrations from Ohio into Vermilion County, IL. A few went on to Green County, WI.

For example, Adam’s namesake son Adam Starr,

spent the last years of life in Clarno, Green County, WI, no more than a few miles from the home of

his cousin, Rachel Starr Strader. (2) Jacob Starr married Anna Maria Weitzel. They had at least two

children. Jacob is thought to have left Guilford County about 1790, but

his later life has not yet been tracked. (3) John Starr would marry Catharine Weitzel.

This pair would become the parents of Rachel Starr. But before elaborating on their lives, let’s take

one more short step backward, and examine the life of the man who was the father to those three

Weitzel daughters, and father-in-law to the three Starr brothers, the man we will refer to at first

as Heinrich Weitzel:

Heinrich Weitzel

This man was probably the son of the “Henrich Weutsel” who travelled on the H.M.S. Elizabeth and

would probably, as a child, have also been a passenger on that voyage. That was probably the very day he

Americanized his name to Henry. From here on down he will be referred to as Henry Weitzel because it is

more in keeping

with the public records. Those records, from Guilford and nearby counties through 1800, variously

render the surname as Witzel, Wetzel, Weitzell, Whitsel, Whitzel, Whitzell, Whitesell,

Whetsel -- as well as Whitesell and Weitzel. This applies not just to Henry but to many

residents of those counties, most or all of whom were likely to have been members of the same extended

clan. What version Henry himself would give us were he alive to be interviewed today is hard to say.

Weitzel has been arbitrarily chosen as “official” here, though in fact a number of his children

appear to have endorsed the idea that they should make themselves appear more English than German and

were strongly tending to use Whitesell in their later years.

A Brief History of Alamance County reports that the Weitzel family of that region came

from between Nurnberg and Dusseldorf in Germany, resided for about five years in Pennsylvania,

moved to North Carolina in 1750, and settled on Gun Creek. This source (quoted in turn in the

Fox Family History, published by the Fox Family Reunion, Ashland, KS, 1976) goes on to say that,

“This history also confirms (Fox) family tradition in that Adam Weitzel of Orange County (now

Alamance County) was a brother of Henry Weitzel of Guilford County, the two actually residing

only a few miles apart. This relationship for them is probably correct, even though it appears

Adam was probably as much as ten to fifteen years younger than Henry. The area along both sides

of the present Guilford/Alamance County line was settled beginning about 1745 almost exclusively

by Germans. Alamance County was created in 1848, mostly from Orange County, but with a small

portion coming from eastern Guilford County, with later additions from northeastern Chatham

County.”

The above excerpt is the first of many that place Henry (or perhaps his namesake father) in this

particular part of North Carolina.

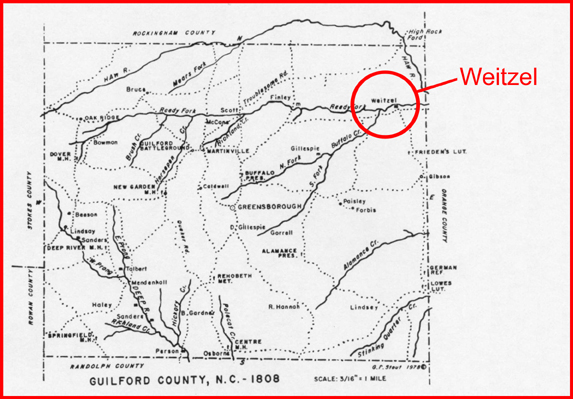

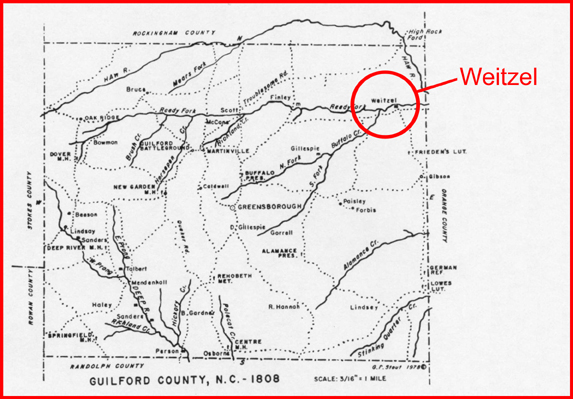

Below is a map from 1808 that is helpful. Note the place name Weitzel in the upper right, circled

and highlighted in red. This may well have been Henry’s precise place of residence for much of

his life, and if not, was the place other members of his family were living, and he resided close by,

probably just to the east in what was at that time known as Orange County.

As Henry Whitsel, Henry appears on the 1755 tax list of Orange County, which at that time included

an area extending several miles inside present-day Guilford County. By 1762 he was a property owner

along the waters of Alamance in what is now Guilford County. On 22 September 1770 Henry

Weitzel took the oath prescribed by Parliament for naturalization at Hillsborough, Orange

County. Henry (name spelled Weitzell) is recorded in the Brick Reformed Church records as a

donor and collector of monies for the church in 1772. In Guilford County records, Henry is mentioned

at least two dozen more times, including as a juror (1783), an assessor (1783), a purchaser of

land (1762, 1763, twice in 1784, 1787), a recipient of land grants (1779, 1780, 1784, 1787,

1790, 1794), a seller of land (1773, 1785, twice in 1788, 1791, 1792, 1793, 1795), road overseer

(1788), an executor (1791), and as a deceased owner (1797, 1798, 1806). All three Starr sons-in-law

appear in these records, especially Adam Starr. In particular, Adam’s name appears as administrator

of Henry’s estate. The names of Henry’s sons Tobias Weitzel and Henry Weitzel, Jr. also appear

more than once.

Many of the records cited above confirm that Henry was the owner

and operator of a mill along the Reedy Fork of the Haw River, and that he was a property owner along

Beaver Creek. This means he may well have been the owner of the 1770s version of the mill shown at left,

which is located on the Reedy Fork near Beaver Creek. The photo is a modern-day picture of an existing

structure, still in operation and selling its flour not only to the local community but to the tourist

trade. The website of this business does not specifically mention Henry by name in the brief summary it

provides of the mill’s history. (Click here

to visit said website.) However, the possibility this is “the” mill -- rebuilt and slightly relocated --

is too tantalizing to neglect to include the photo here. That possibility aside, it is a fact that Henry's

mill was the site of a colorful historical incident. A minor skirmish of the Revolutionary War, to

become known as the Battle of Whitsell’s Mill, took place in 1781 on Reedy Fork, Guilford County.

British troops decided to occupy and make use of the mill, and local men briefly -- and unsuccessfully --

tried to prevent the seizure of the premises.

Many of the records cited above confirm that Henry was the owner

and operator of a mill along the Reedy Fork of the Haw River, and that he was a property owner along

Beaver Creek. This means he may well have been the owner of the 1770s version of the mill shown at left,

which is located on the Reedy Fork near Beaver Creek. The photo is a modern-day picture of an existing

structure, still in operation and selling its flour not only to the local community but to the tourist

trade. The website of this business does not specifically mention Henry by name in the brief summary it

provides of the mill’s history. (Click here

to visit said website.) However, the possibility this is “the” mill -- rebuilt and slightly relocated --

is too tantalizing to neglect to include the photo here. That possibility aside, it is a fact that Henry's

mill was the site of a colorful historical incident. A minor skirmish of the Revolutionary War, to

become known as the Battle of Whitsell’s Mill, took place in 1781 on Reedy Fork, Guilford County.

British troops decided to occupy and make use of the mill, and local men briefly -- and unsuccessfully --

tried to prevent the seizure of the premises.

None of the available references provide precise birth and death dates for Henry and his wife, nor

the birthdates for the majority of their children, but the following stats seem to be accurate: Henry was

born about 1728, probably in Germany. His wife was Anna Maria Fronich. Some references include the

name Sophronia but this is probably a misrendering of Fronich. She was born about 1729. Whether

she came from the same part of Germany as Henry is unknown. The couple were wed about 1748 in Guilford

County. Their ten children, born from 1749 to 1762, were Petrus, John, Heinrich (Henry, Jr.), Margaret,

Samuel, Catharine, Anna Maria, Elizabeth, Phillip, and Tobias. This is believed to be the birth order.

Intriguingly, Anna Maria Fronich’s name appears on some of the property transaction records mentioned

above. Furthermore it is her maiden name -- or variations of it, usually the Americanized version,

Mary Froney. These documents date from late in the marriage, and do not seem to involve property

that came as part of her dowry, nor can it be explained by widowhood, because she pre-deceased Henry.

Perhaps she took charge of her life more than the typical woman of her era.

Henry and Anna Maria finished their lives in Guilford County. She died in the early 1790s. Henry’s

death can best be determined by letters of administration on the estate of Henry

Whitezel, deceased, issued to Adam Starr, Esquire, in 1797. An estate sale was held and was

reported to the February 1798 court.

The three Starr/Weitzel marriages occurred in the mid-1770s, during Henry’s prime as a landowner,

miller, and man of his community. Adam and Margaret were married 22 April 1773. Jacob and Anna Maria

were next, wed on 5 January 1776, followed less than three weeks later by John and Catharine on 25

January 1776. All three weddings took place in Guilford County. All three couples began having children

immediately, and those offspring arrived at frequent intervals.

John and Catharine were said by Rachel Webb to have had twelve children, but Rachel Webb gave the names of

only seven in her notes, and only three others have been identified from other sources. The missing

two were probably lost at birth or while they were very young. The ten whose identities are known are:

John Henry Starr, Mary Elizabeth Starr, John Barnhart Starr, followed by Sophia, Catherine, Naomi,

Daniel, Margaret, Absalom, and finally Rachel. More than one source agrees that Rachel was the

very youngest, born 23 June 1799.

Rachel was born before her family left Guilford County, but she was not more than ten years old

by the time the household was reestablished in Preble County, OH. It was probably only after getting to

Ohio that she became acquainted with

Jacob Strader. Though both the Strader Family and the Starr and Weitzel families originated in Guilford

County, they seem to have lived in slightly different areas and may not have directly known one another.

In Preble County, however, they were in fairly close proximity. Jacob and Rachel probably met when they

were nine or ten years old. As mentioned above, they wed at age eighteen.

Jacob and Rachel had ten children, the first born nine months after

the wedding and the last coming when Rachel was at the extreme end of her fertile years. These ten, as

they appear in the Jacob Strader family Bible, were Mary Ann Marie (“Polly”) Strader, (b. 20 June 1819),

Susan Anna Strader (b. 29 July 1821), Elizabeth Strader (b. 25 Jan 1824), Anna Catherine Strader (b. 11

May 1826), Hannah Strader (b. 30 June 1829), Margaret Ellen Strader (b. 12 March 1831), Daniel Strader

(b. 11 March 1835), John S. Strader, (b. 22 January 1838), Rhoda Carolyn Strader (b. 25 March 1842), and

Jacob Strader, Jr. (b. 15 November 1844).

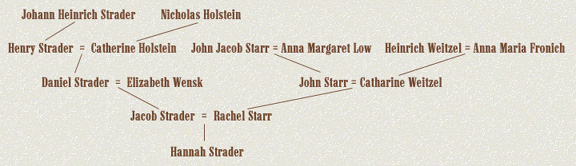

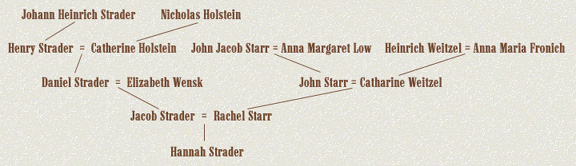

Hannah’s known ancestry tree therefore looks like so:

The Birth Family of Hannah Strader

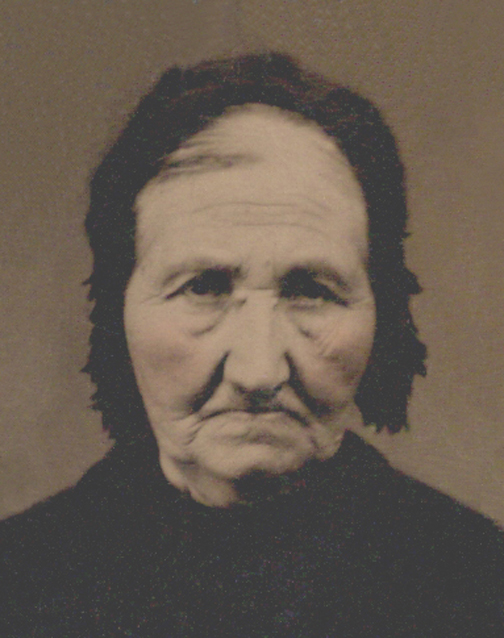

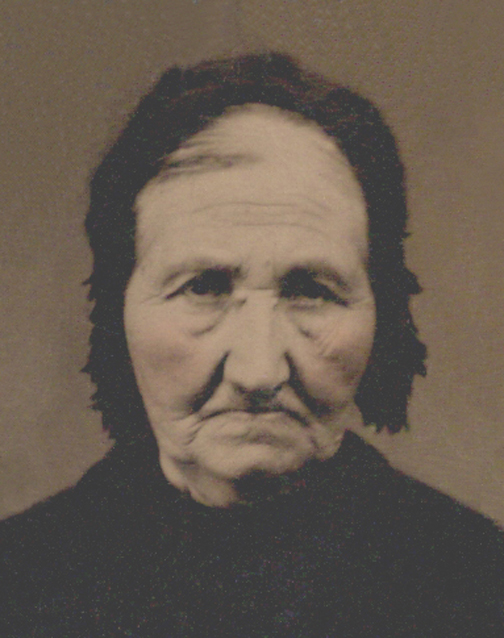

Hannah’s mother Mrs. Rachel Starr Strader in old age

In Preble County, the families mentioned above -- the Straders, the Weitzels, the Starrs, etc. --

began to give in to the great American melting-pot phenomenon. The spouses chosen by the new generations

of the family were often not of German and/or Pennylvania-Dutch extraction. However, this mingling

continued to obey a familiar pattern. The weddings were not just unions of a given man and a given

woman. They were examples of a whole community blending together. Whether the

groom’s forebears had come from the fens of Ireland and the bride’s from the Rhine Valley farmlands of

Germany, the two of them were most likely to have been neighbors for most or all of their lives. Their

families probably all attended the same church. They were almost all dependent on agriculture for

their livelihoods. They were all pioneer,

frontier-dwelling settlers. Often multiple individuals of one immediate family would chose to marry

members of another immediate family, just as the three Starr boys had married the three Weitzel girls. It

was with this Preble County phase that a mingling began between the Strader and the Frame clan. The Frames

had arrived in Preble County in the mid-1810s from Kentucky. The first instance of a wedding occurred when

acob Strader’s sister Polly married Silas Frame in

1821. Twenty-two years later John Strader (who was much younger than Jacob and Polly) would marry Rachel

Frame. By then, the next generation had started to get in on the act, as will be described below. It

is accurate to say that all these people were on a single journey. It was not individuals, but an

entire community, that moved from the Palatinate to the Netherlands in the early 1700s. It was a

mass migration from Europe to North Carolina in the mid-1700s, a common destiny driving the North

Carolina-born generation into Ohio. And the journey was not done. By the late 1820s and early 1830s,

the new generations of these interconnected families would head on Vermilion County, IL. Many would,

in the 1840s and early 1850s, proceed north to the Pecatonica River region -- Stephenson County, IL,

Green County, WI, and Lafayette County, WI.

Jacob Strader and Rachel Starr made the move to

Vermilion County in 1822, joining her sister (Mary) Elizabeth and brother-in-law Henry Johnson and

acquiring a homestead nearby amid a mini-colony of Starr relatives that included not only Lizzy and

Henry, but additional siblings Margaret Marsh (now a widow) and Absalom Starr, and soon to be joined

by Naomi (“Polly”) Jordon and husband John. Coming along with the latter in 1824 were Rachel’s elderly

parents, John Starr and Catharine Weitzel. Twenty-four-year-old Esau Johnson, eldest son of Lizzy and

Henry, served as their guide. The mini-colony may have been the very first settlement in all of what

is now Vermilion County, given that Elizabeth and Henry first occupied their log cabin in 1815. The

locale was known as Johnson’s Point in honor of Henry. That name ceased to be used after the 1830s,

but various sources confirm the cluster of farms lay two miles west of where the village of

Georgetown would eventually rise. All the children from Elizabeth to Daniel were born on the homestead

at Johnson’s Point, and possibly John as well.

Jacob Strader and Rachel Starr made the move to

Vermilion County in 1822, joining her sister (Mary) Elizabeth and brother-in-law Henry Johnson and

acquiring a homestead nearby amid a mini-colony of Starr relatives that included not only Lizzy and

Henry, but additional siblings Margaret Marsh (now a widow) and Absalom Starr, and soon to be joined

by Naomi (“Polly”) Jordon and husband John. Coming along with the latter in 1824 were Rachel’s elderly

parents, John Starr and Catharine Weitzel. Twenty-four-year-old Esau Johnson, eldest son of Lizzy and

Henry, served as their guide. The mini-colony may have been the very first settlement in all of what

is now Vermilion County, given that Elizabeth and Henry first occupied their log cabin in 1815. The

locale was known as Johnson’s Point in honor of Henry. That name ceased to be used after the 1830s,

but various sources confirm the cluster of farms lay two miles west of where the village of

Georgetown would eventually rise. All the children from Elizabeth to Daniel were born on the homestead

at Johnson’s Point, and possibly John as well.

After fifteen years, the family gave in to the temptation to go north. In the wake of the Black Hawk

Wars of the early 1830s, northern Illinois and southern Wisconsin were free of Indian aggression and there

were plentiful opportunities to homestead farmland or dig for lead in the mines of Lafayette County. Jacob

and Rachel again journeyed in the wake of Elizabeth and Henry Johnson, proceeding in a large convoy of

oxen-drawn wagons and livestock in the company of various relatives and neighbors. Rachel Webb’s history

provides us with elderly John Starr’s comment to his son-in-law as they were setting out: “Jake, if I

thought you could get coffee in the new country, I’d go with you.”

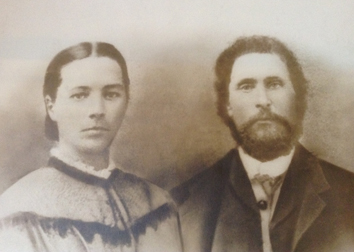

(It is useful to compare the two images of Rachel Starr Strader you see in this section. The

large one is better quality, scanned from an original tintype in the possession of great great great

grandson Dave Smeds, but the exposure was not the best it could have been. The contrast is so high that

the black lace bonnet Rachel was wearing looks more like a black wig. The details of the bonnet are more

apparent in the image at right. Unfortunately the latter had to be scanned from a snapshot taken in the

early 1970s by Leah Hastings Schumacher of a framed print hanging on the wall of a now-unidentified

relative’s home and not from an original -- note the glare from the flashbulb on the glass. With luck,

the original will someday be located and a better scan made.)

Jacob and Rachel, along with many of the other members of their travelling party, settled at first in

Stephenson County at Waddams Grove. (In the 1884 History of Green County, Wisconsin, the

Straders were said to have first come to the place known as Richland Timber, but this is unfortunately

no longer a useful place reference, as the term has fallen completely out of use, and seems to have

applied to a long stretch of woodland, rather than an individual settlement.) Jacob and Rachel’s

immediate neighbors there included Lizzy and Henry Johnson, and two of Rachel’s double first cousin

Adam Starr’s grown sons, Henry Starr and Levi Starr. The latter were brothers-in-law of Esau Johnson,

Esau having married his double second cousin Saloma (“Sally”) Starr.

In about 1845, not long after the birth of Jacob, Jr.,

the family established a new farm over the border in Green County, WI in Jordan Township. Among the

bachelors frequenting Stephenson and Green Counties in the late 1840s was Nathaniel

Martin, who would soon take notice of Hannah, or vice versa. (For more on that, proceed to Hannah’s

biography page. Click here to go straight there.)

In about 1845, not long after the birth of Jacob, Jr.,

the family established a new farm over the border in Green County, WI in Jordan Township. Among the

bachelors frequenting Stephenson and Green Counties in the late 1840s was Nathaniel

Martin, who would soon take notice of Hannah, or vice versa. (For more on that, proceed to Hannah’s

biography page. Click here to go straight there.)

Because Jacob and Rachel and their children established themselves in Wisconsin as a unit, Hannah’s

kin were around her as an adult to a greater degree than her husband’s kin were around him. Several

of Nathaniel’s siblings never came west from Virginia at all, and his parents only arrived when they

were elderly. By contrast, all of Hannah’s siblings spent years in or near Green County. Some

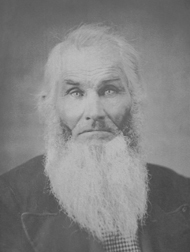

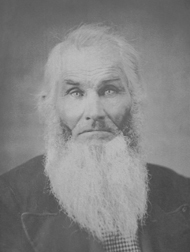

finished their lives there. Parents Jacob and Rachel passed away in Green County as well, beginning

with Jacob 28 February 1865. Jacob was buried in Kelly Cemetery (sometimes called Kelly/Franklin

Cemetery) in Cadiz Township. Rachel thereafter lived with one or another of her children. The 1870

census shows her in the household of son John and his young family on his farm in Clarno Township. In

1880, she is with widowed daughter Rhoda and Rhoda’s two daughters in Cadiz Township a bit north of

Martintown. Her nephew Esau Johnson wrote of visiting her there in May, 1880 -- as he put it, it was

the first time he had seen his aunt (who was only one year older than Esau) in 53 years. Esau had

left Vermilion County for good in 1827. Rachel survived her husband

by more than two dozen years, finally passing away in Martintown 8 March 1889 at just under ninety

years of age. Her remains were also laid to rest at Kelly Cemetery. Jacob and Rachel share a grave

and a tombstone. (The gravemarker is shown at left. Photo taken by Robert Carpenter 1993. Note that

this gravemarker is relatively new. The original marker is nearby. It is not in good condition and

some descendant -- probably Florence Mauermann Behrens -- must have been motivated to commission a

replacement that would remain legible into the 21st Century and beyond.)

While it is not possible to describe the entire line of descent of Jacob Strader and Rachel Starr with

the sort of attention that has been devoted to Hannah’s family, what you see below is hopefully a good

start. Hannah survived until 1919 so she would have been aware of much of the information, and it feels

right to have it here. Please be aware that this section is a work-in-progress. From 2005 to the end of

2014, each of Hannah’s siblings only received a paragraph or two of coverage. Now there is more, with

the added goal of saying at least something about each of her nieces and nephews. Eventually this

material will be more than just a section on the page about her ancestry, and will have its own

dedicated page. However, that will take some time to complete. As of now (March, 2016), you will not

see the expanded coverage about the children of Hannah’s sisters Elizabeth, Anna Catherine, and

Margaret. That will come later. Meanwhile it didn’t seem right to hold the rest back.

Mary Ann Marie “Polly” Strader

Mary Ann Marie “Polly” Strader was perhaps the

sibling who had the most impact on Hannah’s life. In a way this is surprising because Polly was a full ten

years older than Hannah and was gone from the bevy of the family home by the time Hannah was seven to eight

years old. The two siblings did not get the chance to spend much time together as adults until the mid-1850s

when Polly settled on a farm less than ten miles from Martintown. After that, though, Polly and/or her

family members maintained regular and extended contact. A number of

Polly’s children and grandchildren would go on to have a week-by-week presence in Hannah’s life. Of all the

lines that spring from Jacob Strader and Rachel Starr, it is Polly’s clan that today is represented in

the greatest proportion in Green County, WI or spots nearby -- and this was the case to an even greater

degree during Hannah’s lifetime. (By contrast, Hannah probably never again laid eyes on her sister Susanna

or any member of Susanna’s family from 1853 onward.) Polly was also one of the longest-lived of the

Strader/Starr offspring and therefore Hannah was able to spend time with her oldest sister

right up into the 20th Century, something true of only two other siblings, both much younger than Hannah.

Mary Ann Marie “Polly” Strader was perhaps the

sibling who had the most impact on Hannah’s life. In a way this is surprising because Polly was a full ten

years older than Hannah and was gone from the bevy of the family home by the time Hannah was seven to eight

years old. The two siblings did not get the chance to spend much time together as adults until the mid-1850s

when Polly settled on a farm less than ten miles from Martintown. After that, though, Polly and/or her

family members maintained regular and extended contact. A number of

Polly’s children and grandchildren would go on to have a week-by-week presence in Hannah’s life. Of all the

lines that spring from Jacob Strader and Rachel Starr, it is Polly’s clan that today is represented in

the greatest proportion in Green County, WI or spots nearby -- and this was the case to an even greater

degree during Hannah’s lifetime. (By contrast, Hannah probably never again laid eyes on her sister Susanna

or any member of Susanna’s family from 1853 onward.) Polly was also one of the longest-lived of the

Strader/Starr offspring and therefore Hannah was able to spend time with her oldest sister

right up into the 20th Century, something true of only two other siblings, both much younger than Hannah.

Frustratingly, even though Polly and her descendants were so well known to Hannah herself, a number of

questions have developed in the past hundred years about Polly and her story. One uncertainly is to what

degree Polly embraced her nickname. She is called Polly in old family notes and is described as Polly in

the probate file paperwork created in 1852 and 1853 during the interval when her late first husband’s

estate was being settled. But she appears in virtually all other documents under an array of other names

including Mary, Mary Ann, Anna, and Marie. We will continue to call her Polly here, but this is not to be

taken as a declaration of her “true” identity.

One of the most authoritative sources about Polly in recent years was her great-granddaughter Florence

Mauermann Behrens (1910-2000). Florence, a former schoolteacher, became a dedicated historian and family

researcher. She served the town of Brodhead, Green County, WI as chair of the mayor’s historical

preservation committee and she oversaw the efforts of the Brodhead library history room even in the 1990s

when she was quite elderly. This means Florence was skilled as a genealogist and succeeded in finding out

facts about Polly that eluded others. Moreoever, Florence had access to Polly’s own personal

papers, which at the time Florence studied them were owned by her aunt, Blanch Sophia Whitehead Roderick,

who had them from her mother Rhoda Cathryn Frame Whitehead. Unfortunately, even Florence did not have all

the answers about Polly and her life. And even more unfortunate, Florence did not survive long enough to

serve as a direct consultant when this website began to be assembled in 2005. Compounding this is the loss

decades ago of most of the original trove, including Jacob and Rachel’s Bible, which Blanch’s grandchildren

did not preserve.

Polly was already in her late teens by the time of the big family migration from Vermilion County to

Stephenson County. She came along on the trip, but in fact she may not have done so as a daughter of Jacob

and Rachel, but as a wife of William Swearingen. The latter may even have been one of the influences that

caused Jacob and Rachel to move. Jacob and Rachel knew they could depend once again on the

anchoring presence of Elizabeth and Henry Johnson, but their new son-in-law William had already visited

Stephenson County. William, a son of Daniel Swearingen and Lydia Peters born to that couple in Kentucky

30 September 1816, was a river trader. During the early to mid-1830s as a teenager and young man,

he had made a number of runs between the more settled parts of southeastern Illinois and the

newly-opened-for-settlement lands in northwestern Illinois and southern Wisconsin Territory. (The latter

did not actually exist in the jurisdictional sense when William began these journeys; it was part of Michigan

Territory through 1836.) Assuming

William recommended the Pecatonica River region as a fresh place for his new parents-in-law to live, that

may have been the final endorsement Jacob and Rachel needed in order to make up their minds.

Florence Behrens’s notes say Polly and William were wed 24 September 1837 in Stephenson County. This date

and place seem credible, but there is a statistical conflict that must be taken into account. Florence

lists the couple’s first child as Susannah Swearingen, born 7 February 1837, died 12 March 1844 in Vermilion

County. This birthdate is before the wedding date. Perhaps the wedding actually took place 24 September

1836, a date which would imply the ceremony occurred in Vermilion County, not in Stephenson. Perhaps the

birthdate was actually 7 February 1838. Either of those changes would put the wedding before the birth. Four

and a half months prior, actually. This would have meant Polly was pregnant as a bride. This is believable.

What is not as credible is the idea that Susannah was born out of wedlock. The Straders were religious

enough that this would not have been an acceptable scenario and it is not likely things happened that way.

There are two other possibilities: 1) William may have been a recent widower when he married Polly, with

Susannah being the product of a brief marriage to a woman who died in childbirth. However, this theory has

no evidence to support it. 2) Susannah may not have existed. Florence may have found records of a Susannah

Swearingen with that birthdate and death date in cemetery records of Fischer Graveyard in Covington,

Vermilion County, IL and decided she must have been Polly and William’s daughter. It is possible Polly and

William only had five children. Florence is pretty much the only source for the extra pair. The five whose

existence is unquestioned consist of Mary Jane, born in 1838 or 1839, Lydia Elizabeth, born

13 December 1842, Rachael, born 25 December 1844, Sarah Jane, born about 1846, and William Henry Swearingen

(possibly a Junior), born 23 June 1848. Florence included Susannah and one other

child who died before reaching adulthood. She names that last child as Isaac, born about 1848, and Florence

says he died at the age of twelve or thirteen of an intestinal complaint caused by “green apples.”

While traces of Susannah can be found -- an example being the 1840 census which shows the William Swearingen

household contained two little girls who would correspond to Susannah and Mary Jane -- there is no

confirmation Isaac ever existed. He is not in the household in the 1850 census, for example.

The children, whether there were five or seven, were not all born in the same home. William’s occupation

must have required him to keep seeking new opportunities. Mary Jane was born somewhere in Wisconsin. In

1840, as shown by the census, the family home was in Stephenson County near the Strader homestead. Once

the children were more numerous and more mobile,

though, a steadier arrangement would have become vital, and it would appear that Polly and William chose

Vermilion County as their base of operations -- or at least, they were there more often than anywhere else.

They were enumerated there in the 1850 census. Polly is unique among the children of Jacob Strader and

Rachel Starr in coming back to the family’s former stomping grounds. Her parents and siblings never resided

there after the 1836-37 exodus.

William Swearingen died 8 June 1852 in Vermilion County. Now a single mother, Polly did the natural thing

and sought the company and support of her parents in Green County. This brought her back into the same social

circle as her siblings. Her need for another husband and breadwinner was obvious and she did not remain a widow

long. However, her second marriage was not successful. Her niece Juliette Martin Savage wrote in 1947 that

Polly “only lived with her second husband a short time.” Florence Behrens notes this marriage was to a man

named Starr or Blair, but apparently Florence was unable to learn anything more about the fellow than these

two possible surnames. Both names are intriguing and are cause to wonder if Florence got her facts right.

The name Starr suggests Polly married a Starr cousin. Certainly there a great many Starr cousins in the area

who might have been the source of such a groom. The name Blair suggests she may have wed an uncle of

Adelaide Blair, the eventual bride of Polly’s brother John Starr Strader. There is a possible date and place

for this wedding -- 24 November 1853 in Cadiz Township (probably in Martintown). In some family notes

this date and place is used in association with William Swearingen’s death, but the 1852/Vermilion County

stats seem to be accurate, meaning the 24 November 1853 date must have some other reason to have been

jotted down. The timing and place sound right for Polly’s second set of nuptials. All that can be said for

sure about the second marriage is that it was brief. It seems likely that it ended with an annulment

rather than a divorce.

Polly went on to marry Silas Frame 31 October 1855 in Argyle Township, Lafayette County, WI. When she had

been born back in 1819 in Preble County, Silas had been an eleven-month-old baby on a neighboring farm, so it

could be said their connection “went way back.” The union was

one of the six Strader/Frame marriages referred to at the top of this page, and part of a trio involving three

of Hannah’s sisters and a set of three Frame brothers. The marriage of Polly and Silas is not to be

confused with one that occurred a generation earlier when Silas Frame, an uncle of the three Frame

brothers, became the husband of Jacob Strader’s sister Polly Strader. Yes, that means that for two

generations in a row, a Silas Frame married a Polly Strader! Sorting out which is which is a

genealogical challenge unless one pays attention to the dates and places. The older Silas Frame/Polly

Strader pair lived out their lives in Preble County, OH. The younger pair established themselves as

newlyweds on a farm in Clarno Township, Green County, WI and stayed put. Silas in fact died on that

farm in 1894, after which Polly spent most of her final years there.

Though Polly came to her marriage to Silas at over thirty-five years of age, she had an additional four

children. They were Jacob Strader, born in 1856, Rhoda Cathryn, born 10 January 1858, Ellen, born in the

spring of 1860, and Emma Frame, born 22 November 1861. That means Polly was the mother of at least nine,

and possibly eleven, biological children. Impressive as that is, it is only a fraction of the mothering

she did. She was the foster mother of several of her grandchildren. Her daughter Mary Jane died in the

early 1870s. Within a dozen years four more such tragedies would follow. Lydia, Sarah, and William

Swearingen would perish in their thirties, and Jacob Frame in his twenties. In her 1947 letter, Juliette

Savage stated that all of these first cousins of hers died of tuberculosis. All these five except Jacob

produced children before they expired. Polly and Silas came to the rescue

time and time again. They accepted full custody of grandsons Silas Edward Trickle and Ashford Lewis

Trickle. Several other grandchildren spent substantial periods in their home until their surviving

parents had remarried and were able to handle the responsibility.

Polly was widowed again by the death of Silas in 1894. She stayed put in her home for a few years,

then spent the last fragment of her life residing with her daughter Rhoda and son-in-law Charles E.

Whitehead on their Clarno Township farm, and perished there at ten o’clock in the morning of 27 June

1905 about four weeks after a severe collapse of health brought on by old age. She was eighty-six years

old. Of her siblings, only Hannah would surpass that mark. She was buried with Silas in Kelly/Franklin

Cemetery. (Gravemarker shown above left.)

Polly’s offspring were, as a group, probably more a part of Hannah’s life than any other set of nieces and

nephews. Here is a summary of each of their lives (not counting Susannah and Isaac Swearingen, in view of

the fact that they may not have existed):

Mary Jane Swearingen married Loren Brewster Devoe 4 April 1861 in Clarno Township. They became

parents of three children -- William Carlos, Charles Henry, and Cordella (aka Della) -- in the 1860s. In

the early 1870s the couple moved to a farm in Cadiz Township in the vicinity of Martintown, where Mary

Jane soon passed away, becoming the first of Polly’s children to be taken by tuberculosis. Loren lingered

in and/or near Martintown for many years to come,

marrying a second and then a third wife and siring a son with each. Hannah was particularly well acquainted

with her grand nephew Charles Henry Devoe, who made Martintown his base for nearly the whole of the span

during which he and his wife Fannie Long raised their eleven children. (And when they weren’t based in

Martintown, they were only a few miles away in Browntown). The Swearingen-Devoe branch has tended to remain in

Wisconsin more than other parts of the Strader/Starr clan, many of the others having abandoned the area

quite early on. Even today Charles’s great-grandson Duane Devoe lives only a dozen miles from Martintown.

(Duane is one of the modern-day relatives who has contibuted information for this website.) Mary Jane’s

son William Carlos Devoe was an exception, leaving for Iowa as a young man and then spending his final

decades in Missouri. Loren Brewster Devoe survived until 1916, passing away in Waterloo, IA, having spent

his final few years with his youngest son (by third wife Ariel Howe) George Loren Devoe.

Lydia Swearingen married Robert Edward Trickle,

Jr. (aka Trickel). The couple spent their marriage farming in Green County. Lydia, too, would die of TB,

but she did not succumb until the latter part of the 1870s when she was almost forty years old, so hers

was a very substantial brood -- much more so than her siblings and half-siblings. She gave birth to ten

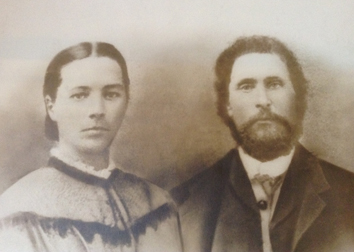

known children, having had an early start on marriage, becoming a wife in 1859 as a teenager. (Shown at

right is Lydia and Robert in what must be their wedding portrait -- and it is literally a portrait, as in

an artist’s rendering and not a photograph. In 1859 Green County, they would have found it easier to have

the image created by an artist than by a photographer.) Two of her elder sons, William and Perry,

married nieces of Loren Devoe. Another of Loren’s nieces married into the Lockman family of Martintown.

The Trickel/Devoe/Lockman clan has been robustly researched by modern-day descendants including Duane Devoe

and as a consequence much of the line of Polly Strader Swearingen Frame is unusually well defined in recent

genealogies. Once Lydia passed away, Robert found it impossible to care for all of such a large group of

children. He placed at least four of the younger kids into foster situations. The group includes the two

youngest boys, Silas Edward Trickle and Ashford Lewis Trickle, whose foster parents were none other than

their grandparents Polly and Silas. The youngest child of all, Nellie May, was taken in by E.C. and Eliza

Gillett, Clarno Township neighbors who were otherwise childless, and they raised Nellie to adulthood in

the village of Monroe. Nellie became known as a Gillett but was kept aware of her birth heritage. (She

probably was a regular visitor at her grandparents’ farm during family get-togethers.) Meanwhile Robert

moved as a widower to Delta County, CO accompanied by or soon joined by sons John, Perry, Andrew Jackson

(Jack), and William. Some did not go quite as far, ending up instead in Dodge City, Ford County, KS.

Younger members of the brood found the Colorado and Kansas options less compelling, perhaps feeling

(understandably so) that they had been left behind. Ashford, after coming of age back in Wisconsin, chose

to settle in Iowa instead. Nellie spent a few decades in Colorado, but finished her life in California.

Lydia Swearingen married Robert Edward Trickle,

Jr. (aka Trickel). The couple spent their marriage farming in Green County. Lydia, too, would die of TB,

but she did not succumb until the latter part of the 1870s when she was almost forty years old, so hers

was a very substantial brood -- much more so than her siblings and half-siblings. She gave birth to ten

known children, having had an early start on marriage, becoming a wife in 1859 as a teenager. (Shown at

right is Lydia and Robert in what must be their wedding portrait -- and it is literally a portrait, as in

an artist’s rendering and not a photograph. In 1859 Green County, they would have found it easier to have

the image created by an artist than by a photographer.) Two of her elder sons, William and Perry,

married nieces of Loren Devoe. Another of Loren’s nieces married into the Lockman family of Martintown.

The Trickel/Devoe/Lockman clan has been robustly researched by modern-day descendants including Duane Devoe

and as a consequence much of the line of Polly Strader Swearingen Frame is unusually well defined in recent

genealogies. Once Lydia passed away, Robert found it impossible to care for all of such a large group of

children. He placed at least four of the younger kids into foster situations. The group includes the two

youngest boys, Silas Edward Trickle and Ashford Lewis Trickle, whose foster parents were none other than

their grandparents Polly and Silas. The youngest child of all, Nellie May, was taken in by E.C. and Eliza

Gillett, Clarno Township neighbors who were otherwise childless, and they raised Nellie to adulthood in

the village of Monroe. Nellie became known as a Gillett but was kept aware of her birth heritage. (She

probably was a regular visitor at her grandparents’ farm during family get-togethers.) Meanwhile Robert

moved as a widower to Delta County, CO accompanied by or soon joined by sons John, Perry, Andrew Jackson

(Jack), and William. Some did not go quite as far, ending up instead in Dodge City, Ford County, KS.

Younger members of the brood found the Colorado and Kansas options less compelling, perhaps feeling

(understandably so) that they had been left behind. Ashford, after coming of age back in Wisconsin, chose

to settle in Iowa instead. Nellie spent a few decades in Colorado, but finished her life in California.

Rachael Swearingen married Carlos J. Wells in late 1861. He was a son of Warner Wells, part of a

clan that had come out of Otsego County, NY and become early-arriving settlers of Oneco Township, Stephenson

County. This same Wells clan ties into the Starr clan in multiple ways. For example, Carlos’s brother Orson

Wells (yes, no kidding -- but bear in mind the film-legend actor-director spelled his last name Welles with

an extra “e”) married Martha Ellen Starr. Carlos’s first cousin Thomas Jefferson Wells married Susan Emaline

Starr. Both Martha and Susan were daughters of Solomon Starr, one of Esau Johnson’s brothers-in-law. As

newlyweds, Rachael and Carlos settled down on a farm in Rock Grove Township, Stephenson County, IL, and that

was where they remained for good. They produced four children -- William Warner, John E., Cora Ellen, and Lura

Ann Wells -- at the sensible pace of about one child every five years. They also took in Olive Wolf, daughter

of Rachael’s late half-sister Emma Frame, when Olive was a teenager (perhaps simply to have a servant, as she

is described in the 1900 census, or perhaps to let the girl get out of her stepmother’s house). Carlos was

apparently popular within the clan. A number of Rachael’s nephews and grand-nephews were named Carlos (usually

as a middle name) and he seems to have been the source. Carlos died in 1917. Rachael lingered on the farm,

which was in the hands of daughter Cora and son-in-law David Rockey. She reached eighty years of age, making

her the only one of Polly’s kids to come close to matching the number of years Polly herself survived. By the

time of her death Rachael had been a fixture of Stephenson County for over sixty years. Her clan would carry

on that connection and even today descendants inhabit the area. As for her kids, John and Cora remained within

the county for life. William Warner Wells and family eventually relocated to DeKalb County, but in the grand

scheme of things this was not a big shift. He and his household ended up only thirty miles southeast of the

old farm in easy visiting distance. The only one who truly left was Lura Ann Wells, who with her husband Owen

Reed moved to South Dakota in the early 1900s. Her three Reed grandchildren were the only ones Rachael did not

get the chance to see on a regular basis. However, as it happened Rachael was visiting Lura Ann and Owen on

their farm in Brown County when she passed away 17 January 1925.

Sarah Jane Swearingen took a page from her mother’s book and went through a marriage that was over

so quickly it is difficult nowadays to confirm it happened. She wed neighbor Thomas Hackworth 12 March 1865

in Clarno Township. Divorce or annulment must have followed because both Sarah and Thomas appear in the 1870

census married to other people. In Sarah’s case, her second spouse was Stephen Decatur Black. (Called Dick

Black in Juliette Savage’s 1947 letter -- apparently he was nicknamed “Deck” and inevitably some people

started calling him Dick instead. Because of this nickname, a few pre-internet genealogies identified him

as Richard Black.) Sarah and Stephen were wed 19 September 1868 in Green County, WI. Precisely seven weeks

later, Sarah’s younger brother William H. Swearingen married Stephen’s younger sister Hulda D. Black. Stephen

and Hulda were children of David W. Black and Nancy Cable.

As newlyweds, Sarah and Stephen moved in with his parents in rural Cadiz Township near Martintown. David

and Nancy Black had founded their farm in the 1860s after the family had come out west from Tuscawaras

County, OH. Stephen was the eldest son (by quite a margin) and was his father’s right-hand man in caring for

the land, which he continued to do throughout the time Sarah was his wife. The couple produced three

children: Nancy Anna, Rachel Weltha, and Ernest Decatur Black, the first born in 1869 and the last in 1879.

It was while Ernest was an infant that Sarah’s case of tuberculosis manifested in full force. At that point,

in order to lessen the chance that members of her household would contract the disease from her, she retreated

to the sanctuary of her mother and stepfather’s farm in Clarno Township, bringing only young Ernest along and

leaving her husband to look after the girls at home. Sarah passed away in the spring of 1880. Stephen went on

to finish raising the kids back in Cadiz Township before he died in 1898. Because of the proximity, Hannah got

to know her niece’s offspring quite well. Nancy -- better known by her middle name and as Annie, married

Hannah’s nephew David Francis Eveland, which among other things means the genealogical line springing from

them is doubly descended from Rachel Starr and Jacob Strader. Annie and Dave established themselves in the

early 1890s on a farm in Wiota Township, Lafayette County, WI just outside Green County, remaining for good.

Rachel Weltha Black married Milton Whitehead of the same clan as her aunt Rhoda Frame’s husband Charles

Whitehead; they lived out their entire lives within Green County. Ernest Decatur Black moved away to Minnesota

just after the Turn of the Century. He and wife Naomi Roberts did not produce offspring.

William Henry Swearingen and Hulda Black spent the earliest years of their union farming in Clarno

Township, staying more-or-less within the sphere of Polly and Silas Frame. First child Anna was born in Clarno

Township. In the early 1870s the couple spent a short sojourn in Hardin County, IA. Second child William Carlos

was born there. By the middle of the decade (and possibly sooner) William and Hulda decided the Martintown area

appealed to them and they became based in Cadiz Township. The family lingered about twenty-five years, though

William did not live to see the end of that phase because he succumbed to tuberculosis 7 November 1883 at the

age of only thirty-five. By then the family had expanded to six, the four younger ones consisting of Stephen,

Elsie May, Cora Ellen, and Lee Henry (sometimes Henry Lee) Swearingen. Hulda went on to marry Orville Hubbard

in 1891. The ties to Martintown weakened with the late 1890s deaths of Hulda’s parents and her brother Stephen.

Older son William Carlos Swearingen had just become established in Mazomanie, Dane County, WI, so Hulda and

Orville -- who was eighteen years Hulda’s senior and was ready to retire -- also moved to Mazomanie. The two

would finish their lives there, Orville dying in 1927 and Hulda in 1933. Two of her other children, Elsie and

Lee, also put down roots in Mazomanie. Descendants can be found in Mazomanie to this day.

Jacob Strader Frame is not to be confused with his double first cousin of precisely the same name, born

the same year -- 1856 -- and in almost the same place. While his namesake would go on to settle in Nebraska and

then in California, this Jacob Strader Frame by contrast accompanied his brother-in-law Robert Trickle to Delta

County, CO in 1880. He was by then in his mid-twenties and as it happened, had only half a dozen years yet to

live. Jacob is not known to have left any descendants. One

family note states he married a woman named Sarah Curtis, but no corroboration of this has turned up. If this

detail has any truth to it, the union was brief, perhaps leaving him a young widower. Generally speaking very

little is known about him whatsoever. He is known to have carved pieces of wood and assembled them to make

picture frames that are still in the possession of one of his sister Rhoda’s great-granddaughters -- though the

artwork currently in those frames is from the Twentieth Century and no one can say what images Jacob created the

frames for. These artistic endeavors, along with a copy of the telegram about his death preserved in the same

cache of memorabilia preserved by Rhoda and her descendants, are among the only surviving physical items left

that commemorate his existence in any way other than as a name on genealogical lists. Said telegram was written

by Charles Bray, the coroner of Las Animas, CO. It reveals that Jacob drowned in or near Las Animas on Sunday,

22 August 1886. Apparently his companions knew only that he was J.S. Frame from Monroe, WI. On the 24th, Bray

sent his telegram to the postmaster of Monroe asking if any relatives might still live in that vicinity, and if

they existed, what they might want done with the cadaver. Soon the message was relayed to Silas and Polly. As

far as can be determined, the burial took place in Las Animas.

Rhoda Cathryn Frame was the child upon whom Polly came to lean at the end of her life. In some ways

this was inevitable. With the exception of Rachael Swearingen Wells, no other child of Polly survived past

the mid-1880s. Rhoda was born in 1858 and spent her whole upbringing on the Clarno Township farm. In 1877,

she wed Charles Edward Whitehead. The Whiteheads as a whole share a number of other genealogical ties

to the Martin/Strader clan, but this union was the most direct example of the connection. The pair settled

as newlyweds on a Clarno Township farm not too far from Polly and Silas’s property, though far enough away

to provide a bit of a cushion between them. This farm was to be their home for all of Rhoda’s remaining

forty-six years of life, after which Charles lingered there until retiring in his mid-seventies (in 1929 or

1930). Rhoda and Charles produced just three children, a son who died either at birth or in infancy, and two

daughters, Blanch and Naoma, the latter better known as Oma. Rhoda and Charles took in elderly Polly at

about the turn of the century, within half a dozen years after the death of Silas Frame. The old widow would

remain until death. In many ways, it is accurate to describe Rhoda as a chip off the old block. Her temperament