Jakob Herman Smeds

Jakob Herman Smeds, eldest child of Jakob Herman Mattsson

Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs, was born 9 August 1881 on Section 1 of the ancestral Smeds

estate in Soklot, Finland. He grew up on that property. In mid-childhood his mother died. In the

wake of that tragedy, his paternal grandmother Lisa Jakobsdotter Pörkenäs Smeds moved into the home

to help her widower son bring up his kids. Lisa died in 1897, ending her tenure as surrogate mother.

Herman would thereafter get by with the assistance of his brother Erik’s wife Brita, who lived next

door. Brita’s contribution was essential to complete the raising of Jakob’s five younger siblings,

but Jakob’s own case was a little different. Weeks before his grandmother had passed away, Jakob had

already launched into the first phase of his independent life. He had not quite turned sixteen at

the time this occurred, but his father permitted it because Jakob went into a supervised situation

in the small city of Jakobstad as the live-in apprentice of a Mr. Bjorkman -- who was quite possibly

a relative. The training Jakob received during this period, which lasted a year and ten months,

proved to be critical to the destiny of his entire immediate family.

Jakob Herman Smeds, eldest child of Jakob Herman Mattsson

Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs, was born 9 August 1881 on Section 1 of the ancestral Smeds

estate in Soklot, Finland. He grew up on that property. In mid-childhood his mother died. In the

wake of that tragedy, his paternal grandmother Lisa Jakobsdotter Pörkenäs Smeds moved into the home

to help her widower son bring up his kids. Lisa died in 1897, ending her tenure as surrogate mother.

Herman would thereafter get by with the assistance of his brother Erik’s wife Brita, who lived next

door. Brita’s contribution was essential to complete the raising of Jakob’s five younger siblings,

but Jakob’s own case was a little different. Weeks before his grandmother had passed away, Jakob had

already launched into the first phase of his independent life. He had not quite turned sixteen at

the time this occurred, but his father permitted it because Jakob went into a supervised situation

in the small city of Jakobstad as the live-in apprentice of a Mr. Bjorkman -- who was quite possibly

a relative. The training Jakob received during this period, which lasted a year and ten months,

proved to be critical to the destiny of his entire immediate family.

As the 20th Century dawned, young Finnish men found themselves being conscripted into the Russian

Army and sent across Siberia to desolate outposts where many of them perished of the harsh

conditions. To escape that fate, and as a means of civil disobedience against the occupation of

Finland by the Tsarist regime, large numbers of these youths fled to America. Many of them did so

right before turning eighteen, the age when they would begin to be at risk of being seized by the

recruitment forces. However, when Jakob reached eighteen in 1899, the political climate was not as

dire, permitting him to linger in Finland until he was twenty (or nearly so). He either made the

journey across the Atlantic in the latter part of the year 1900, or he did went in 1901. He chose

California as his destination. He would reside in the state for the remainder of his long life. As

he spent more and more time among English-speaking companions, he became increasingly known as

Jack Smeds.

Jack was a wizard with languages and eventually had at least some fluency in five -- his native

Swedish, of course, but also Finnish, German, Russian, and English. It may seem obvious that he

spoke Finnish, but in fact Swedish was the majority language in the region Jack sprang from, and

much or all of his understanding of Finnish probably came after he reached the U.S. and began

associating with Finns from the interior and southern portions of the nation. As a brand-new

immigrant, his command of English was rudimentary, and he was confronted by the same challenges

finding an employer as any foreigner had to endure. His first great strides in learning English

occurred during his early years in the U.S. as he worked as a common laborer in the redwood

forests of northern coastal California near Eureka.

By the time Jack and all of his generation were deceased, the surviving members of the Smeds clan

could not point to any particular reason why Jack chose Eureka as the spot where he would begin to

know America. Descendants conjectured he had ended up there for no reason other than the availability

of a job. However, the choice may not have been as random as that. Various clues found in the course

of research undertaken from 2010 onward imply he came to Humboldt County because he had kinfolk there.

These would have been relatives on his mother’s side, with names like Wickman, Beck (or Bäck), Jacobson,

and of course, Fagernäs. Unfortunately, Jack and all of his generation hated to talk about themselves.

They were reserved and private. This aspect of their character is undoubtedly why the story-behind-the-story

has been lost. “Resisting Tsarist oppression” sounds grand and is the sort of legend that would persist.

“Following Mama’s relatives” is not dramatic, and inasmuch as Jack’s children and grandchildren never

knew any of those relatives (who may have become established in Humboldt County as early as the 1880s),

the connection was forgotten. Unfortunately, because it was forgotten, it has so far been impossible to

definitively say who these relatives were and just how they were related. (For more about this, see the

essay “From Finland to Reedley: The Smeds Family Journey” elsewhere on this website.)

Thanks to his trade skills, Jack was able within two or

three years to shift to a better-paying situation in San Francisco. His new employer was Shreve and

Company, a jewelry firm that had been founded during the Gold Rush (and still exists today). Shreve &

Company was a large-scale full-service company, fashioning not only decorative jewelry but silverware

and other household items, and Jack was tasked with generating a wide variety of merchandise. He was in

place by 1904. That was the year his brother Vilhelm (Billy) and sister Augusta

arrived. They would end up in Eureka, but it is unclear whether they joined Jack in Eureka, and then

Jack moved south, or if they joined Jack in San Francisco and, after a good visit with him there,

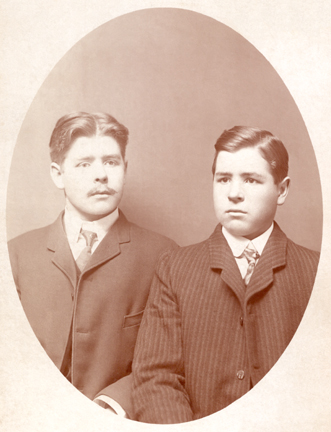

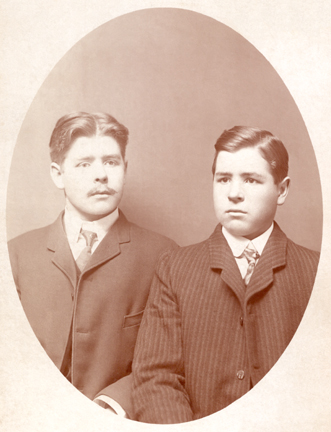

proceeded north to Eureka. (At right is a photograph of Jack and Billy taken in 1904-1906 at Shew’s

Pioneer Gallery, 520 Kearney Street, San Francisco. It may well have been taken in 1904 and suggests Jack

had in fact moved before Billy and Augusta arrived in the country. Having photographs taken upon arrival

to send back to relatives in Finland would have been a natural thing to do. The studio they chose had

quite a history. It had been founded by upstate New York native William Shew early in the Gold Rush --

about the same time, in fact, that Shreve & Company had been founded. Shew

had gone on to operate it for fifty years. By the time Jack and Billy posed, William Shew was recently

deceased and his young widow Anna Katherine Shew had inherited the business. An active photographer

herself, she may have been the very person who took this picture.)

Thanks to his trade skills, Jack was able within two or

three years to shift to a better-paying situation in San Francisco. His new employer was Shreve and

Company, a jewelry firm that had been founded during the Gold Rush (and still exists today). Shreve &

Company was a large-scale full-service company, fashioning not only decorative jewelry but silverware

and other household items, and Jack was tasked with generating a wide variety of merchandise. He was in

place by 1904. That was the year his brother Vilhelm (Billy) and sister Augusta

arrived. They would end up in Eureka, but it is unclear whether they joined Jack in Eureka, and then

Jack moved south, or if they joined Jack in San Francisco and, after a good visit with him there,

proceeded north to Eureka. (At right is a photograph of Jack and Billy taken in 1904-1906 at Shew’s

Pioneer Gallery, 520 Kearney Street, San Francisco. It may well have been taken in 1904 and suggests Jack

had in fact moved before Billy and Augusta arrived in the country. Having photographs taken upon arrival

to send back to relatives in Finland would have been a natural thing to do. The studio they chose had

quite a history. It had been founded by upstate New York native William Shew early in the Gold Rush --

about the same time, in fact, that Shreve & Company had been founded. Shew

had gone on to operate it for fifty years. By the time Jack and Billy posed, William Shew was recently

deceased and his young widow Anna Katherine Shew had inherited the business. An active photographer

herself, she may have been the very person who took this picture.)

In San Francisco, Jack came to know the local Finns. The immigrant community from the mother

country had become well-organized within the city and other parts of the Bay Area, keeping each other

informed and giving each other mutual support through the activities of the fraternal society, the

United Finnish Kaleva Brothers and Sisters, or simply, the Finnish Brotherhood. San Francisco was home

to Lodge No. 1. The reason why Jack had been able to land such a good job was due to these

connections, specifically in the person of Fred Tenhunen, a Finn about nine years Jack’s senior who had

been working for Shreve and Company for a number of years and was able to put in a good word for his

countryman. Jack spent most of his social hours at gatherings of Lodge No. 1, and was active within

the subsidiary organization, the Finnish Temperance Society, as he was one of those Finns who felt that

his countrymen had too much affection for alcohol.

Toward the end of 1904, a guest speaker made a presentation to the Brotherhood chapter. The man was

Axel Wahren, a prominent Finn who had been active in the nation’s politics and had been exiled by

the Tsar’s governor during the preceding year. In his youth, Wahren had attended university in the

United States. While there, he had gained an understanding of cutting-edge farming methods. It was

only natural that when he was forced to leave his homeland, America was his destination of choice,

and given his education and the contacts he had within the U.S. Department of Agriculture, he hatched

a plan to found an agricultural colony made up of Finns. He and a friend, Ernest Rindell, scouted

prospective locations and determined that the area just north and west of the small town of Reedley,

Fresno County, CA would be eminently suitable for that purpose. Accordingly, Wahren wrote up the

details of his plan in a pamphlet, “The Possibilities for a Finnish Agricultural Colony in

California.” The pamphlet met with considerable interest among the Finns of San Francisco, who invited

him to speak to them in person. His listeners found him to be persuasive. Jack and eight other Finns

accompanied Wahren down to the San Joaquin Valley to see the fields of the Reedley area for

themselves.

Ironically, Wahren himself would return to Finland in 1905 when his exile was rescinded, and his

partner Rindell would go on to become a druggist in Astoria, OR. But the plan for “New Finland”

caught fire. Dozens of Finns took Wahren’s advice -- even some who were still in the old country when

they heard about the opportunity -- and over the next fifteen years more and more individuals and

families followed suit, shaping the character of Reedley for good. (Though it must be said, the town

saw equally robust influxes of Russian Mennonites, Japanese, Armenians, and Mexicans during the first

few decades of the Twentieth Century, along with a wave of poverty-stricken Americans fleeing Oklahoma

and northern Texas during the Dust Bowl era.) Some of the new arrivals set up homes right in the

midst of existing neighborhoods and farms, but concentrations of Finns at specific sites resulted in

colonies much like the one Wahren had imagined, only on a smaller scale. These would never be large

enough to result in villages and all faded away as the kids of those households grew up speaking

English, but in the meantime their existence helped many of the immigrants finish their assimilation.

The main clusters included Riverside along the Kings River near the bridge just west of Reedley

proper, Merritt about a mile north of town, and Lac Jac on the western side of the river extending

northward.

Shreve and Company silvermiths at work in 1904. Jack is on the right, fourth man up from

the bottom of the image.

Jack might well have decided to set himself up within one of the aforementioned boroughs if not for a

mitigating factor. Most of the Finns descending upon Reedley were Finnish-speaking Finns, not

Swedish-Finns (or as they often called themselves in America, Finland Swedes) like Jack. In the old

country the two types were separate ethnic groups. The enmity between the two was not as severe as

the distrust found between culturally-different neighbors in other parts of the world, but the two

groups preferred to keep to themselves. Within the melting-pot society of America, Jack felt a kinship

with all Finns, no matter which of the nation’s two official languages they spoke, no matter which part

of Finland they may have come from, but it was another thing entirely to end up in a colony situation

where he was a member of the minority, surrounded by others who might look sideways at him. Fortunately

there were others who shared his concern. They agreed to form a mini-colony made up of “their kind.”

Jack and three companions -- Gust Laine, Fred

Tenhunen, and Karl Nordell -- identified a spot to their liking. About three miles north of

Reedley near the Kings River was a stretch where the soil contained enough clay (that is to say, it

contained an annoying layer of hardpan) that it had not been

developed much in previous decades, being used for little more than hayfields. The price was therefore

low. However, as Axel Wahren pointed out, these parcels could be transformed into highly productive

permanent-crop acreage because the new irrigation project, the Wahtoke Canal, would deliver water via

ditch at intervals all summer long. Jack, Gust, Fred, and Karl agreed to buy farms there. Others would

soon follow suit. Many of them were Finland Swedes -- though not all. In fact, of the original four,

two were not. Karl Nordell was Norwegian and Fred Tenhunen was in fact a Finnish Finn. Friendship

trumped these particulars. The second wave included Abraham Andrew Westerlund. The

latter, in part because he remained a lifelong bachelor, became an honorary member of the Smeds family,

and was known to the younger generations as “Uncle Westerlund” or even as just “Uncle West.”

In January, 1905, Laine and Nordell moved to Reedley,

hurriedly erecting a small cabin (shown at left) on Laine’s land that they would share while

developing their respective parcels. Others would arrive on the farms nearby and soon actual houses

started to appear. Jack, however, did not make his own move during this early period. He took a different

approach. He was earning steady money as a silversmith. As a farmer of undeveloped land, he knew he would

make nothing at all for at least a year. It is believed that he bought his first parcel at the same time

the others did, i.e. at the very end of 1904 or the very beginning of 1905 -- property records need to be

researched to be certain this is true -- but it would be another decade before he became an actual

resident of Reedley. He visited when he could. Otherwise he was to be found in in San Francisco, where

he continued to work at Shreve & Company, earning the funds he needed to pay down the mortgage. If he

did buy early, he probably did nothing during the first three calendar years of ownership beyond planting

alfalfa. This was a step Axel Wahren recommended as a way of fixing nitrogen in the soil and as a means

of generating some quick cash. Wahren had cautioned that skipping such a step and immediately planting

vineyards or orchards would leave impatient farmers with empty pockets just when they needed to make

capital improvements, and in the long run harm the vitality of their trees and vines. Alfalfa was a simple

crop suitable for an absentee farmer to grow. When hay-cutting time rolled around, hired workers could

handle the job just fine. Jack knew he could depend on the good will of neighbors like Nordell, Laine,

and Westerlund to serve as his intermediaries in finding customers for his crop, and keep him from being

cheated. Fred Tenhunen did the same, remaining in Berkeley until 1913. (And then Fred, as it turns out,

decided he wasn’t cut out to be a farmer after all. He and his family stayed in Reedley only seven or

eight years. They left in the early 1920s for Oakland, where Fred resumed his jewelry career. He

sold his farm to Billy Smeds in 1930.)

In January, 1905, Laine and Nordell moved to Reedley,

hurriedly erecting a small cabin (shown at left) on Laine’s land that they would share while

developing their respective parcels. Others would arrive on the farms nearby and soon actual houses

started to appear. Jack, however, did not make his own move during this early period. He took a different

approach. He was earning steady money as a silversmith. As a farmer of undeveloped land, he knew he would

make nothing at all for at least a year. It is believed that he bought his first parcel at the same time

the others did, i.e. at the very end of 1904 or the very beginning of 1905 -- property records need to be

researched to be certain this is true -- but it would be another decade before he became an actual

resident of Reedley. He visited when he could. Otherwise he was to be found in in San Francisco, where

he continued to work at Shreve & Company, earning the funds he needed to pay down the mortgage. If he

did buy early, he probably did nothing during the first three calendar years of ownership beyond planting

alfalfa. This was a step Axel Wahren recommended as a way of fixing nitrogen in the soil and as a means

of generating some quick cash. Wahren had cautioned that skipping such a step and immediately planting

vineyards or orchards would leave impatient farmers with empty pockets just when they needed to make

capital improvements, and in the long run harm the vitality of their trees and vines. Alfalfa was a simple

crop suitable for an absentee farmer to grow. When hay-cutting time rolled around, hired workers could

handle the job just fine. Jack knew he could depend on the good will of neighbors like Nordell, Laine,

and Westerlund to serve as his intermediaries in finding customers for his crop, and keep him from being

cheated. Fred Tenhunen did the same, remaining in Berkeley until 1913. (And then Fred, as it turns out,

decided he wasn’t cut out to be a farmer after all. He and his family stayed in Reedley only seven or

eight years. They left in the early 1920s for Oakland, where Fred resumed his jewelry career. He

sold his farm to Billy Smeds in 1930.)

Back in San Francisco, armed with a plan for the future, Jack’s thoughts turned to the matter of finding

someone with whom to share that future. His attentions fixed upon seventeen-year-old Anna Gustava

Rautiainen. She was also from northern Finland, having grown up in Oulu province in towns and villages

only a few hundred miles northeast of Soklot. He had balked at the idea of becoming surrounded by

Finnish-speaking Finns, but he decided he didn’t want to keep her at a distance at all. The fact

is, the pair were perfect for one another. She was pretty. She was the ideal marriage age by the standards

of the time. The two shared a national background. They had similar values -- for example, their mutual

distrust of alcohol, which had led to them first encountering one another at the temperance hall. He was

a handsome young man with a steady job and a domestic goal in

mind that any prospective wife would adore. And yet they deserve credit for recognizing how well-matched

they were. In the old country, they would not have taken each other seriously as marriage material. Both

were able to let the positive influence of their context take root, and set aside their prejudices. The

result was a til-death-them-do-part union. They were wed 27 May 1905 in San Francisco by Rev. O.

Groensberg. By the end of the year they were parents of their first child, Sylvia Alice Smeds.

Jack and Annie and their two girls in late 1907 or early 1908

The family was living in San Francisco in 1906 when the great earthquake struck. With little more than

their baby, her perambulator, and the clothes on their bodies, Jack and Annie fled the devastation by

ferry, going across the bay to take shelter with friends in Berkeley (which probably means they were

taken in by Fred and Katherine Tenhunen). In so doing they escaped the Great Fire, but their residence

was destroyed. Jack recovered only a

handful of possessions, such as a plate and one of the spoons he had made, which remained in the

family as mementoes and conversation pieces. One of the items saved by carrying it with them on

the ferry trip was a silver coffee pot that had been a wedding gift from Shreve and Company. This

remains within the family today, passed down to Sylvia and then to her daughter Diane Heagerty and

then to Diane’s eldest daughter.

Shreve and Company’s newly-constructed skyscraper on Union Square survived the quake and the fire, but

needed quite a bit of repair. Jack had carpentry skills, so he was among the laborers that got the

structure back in shape. The demand for construction workers continued to be high during the rebuilding

of the burned-out neighborhoods. As a result, for quite some time Jack made his livelihood more as a

carpenter than as a silversmith, and continued to take part-time carpentry gigs as late as 1908. Shreve

and Company cooperated, knowing their long-term prosperity depended on the city getting rebuilt and its

economy back to normal.

Throughout their years in the Bay Area, Jack and Annie

always rented their living quarters -- the Fresno County farm being the only real estate they owned -- but

probably no period was as tenuous in terms of personal circumstances as what they experienced during 1906.

Years later Annie would sometimes mention that they lived in a tent during this time. Whether this was

while they were in Berkeley, or refers to their time in San Francisco after their move back, is not

clear. However, by the end of the calendar year their situation was again secure. And

just in time, too, because they had visitors. Jack was now a naturalized citizen, having wasted no time

in taking that step. He was able to serve as a sponsor for those immediate family members who had yet to

come over from Finland. By now there were only three left -- his father and his youngest siblings Axel and

Amanda, his sister Maria having already crossed the Atlantic in 1905, only to meet a man on the voyage

who proposed to her and took her to live as his wife in New Hampshire. Herman, Axel, and Amanda are known

to have disembarked from the liner Ivernia 20 December 1906 in Boston. A long cross-continental

train trip followed, which probably chewed up the remainder of December. But in early 1907, Jack and

Annie welcomed the travellers at their apartment on 28th Street, just down the hill to the immediate

west of Bernal Heights, not far from the place they had occupied before the earthquake. The newcomers may

have lingered as late as January 17th, in which case they were on hand to witness the arrival of Jack and

Annie’s second child, their daughter Lillian Anna Smeds. Soon, though, Herman, Axel, and Amanda went on

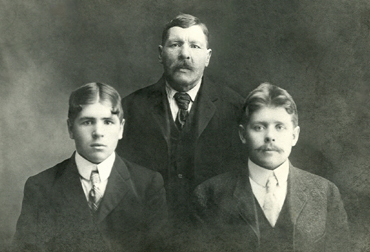

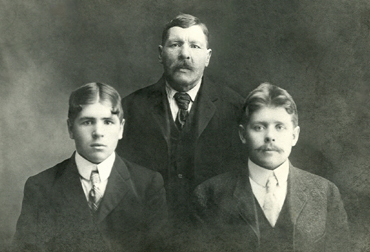

to Eureka, just as Billy and Augusta had done in 1904. (In the image at right, Billy is on the left,

Jack on the right, and their father is in the middle. This picture may have been taken shortly before

Jack left Finland. If not, it was taken in early 1907. Judging by how adolescent Billy appears, the earlier

date is probably the correct one.)

Throughout their years in the Bay Area, Jack and Annie

always rented their living quarters -- the Fresno County farm being the only real estate they owned -- but

probably no period was as tenuous in terms of personal circumstances as what they experienced during 1906.

Years later Annie would sometimes mention that they lived in a tent during this time. Whether this was

while they were in Berkeley, or refers to their time in San Francisco after their move back, is not

clear. However, by the end of the calendar year their situation was again secure. And

just in time, too, because they had visitors. Jack was now a naturalized citizen, having wasted no time

in taking that step. He was able to serve as a sponsor for those immediate family members who had yet to

come over from Finland. By now there were only three left -- his father and his youngest siblings Axel and

Amanda, his sister Maria having already crossed the Atlantic in 1905, only to meet a man on the voyage

who proposed to her and took her to live as his wife in New Hampshire. Herman, Axel, and Amanda are known

to have disembarked from the liner Ivernia 20 December 1906 in Boston. A long cross-continental

train trip followed, which probably chewed up the remainder of December. But in early 1907, Jack and

Annie welcomed the travellers at their apartment on 28th Street, just down the hill to the immediate

west of Bernal Heights, not far from the place they had occupied before the earthquake. The newcomers may

have lingered as late as January 17th, in which case they were on hand to witness the arrival of Jack and

Annie’s second child, their daughter Lillian Anna Smeds. Soon, though, Herman, Axel, and Amanda went on

to Eureka, just as Billy and Augusta had done in 1904. (In the image at right, Billy is on the left,

Jack on the right, and their father is in the middle. This picture may have been taken shortly before

Jack left Finland. If not, it was taken in early 1907. Judging by how adolescent Billy appears, the earlier

date is probably the correct one.)

Jack and Annie again played host to a gathering for the Christmas and New Year holiday season as

1907 turned into 1908. Those present probably included all of the California-based members of the Smeds

family, i.e. Jack, Annie, Sylvia, and baby Lillian, along with his father, his siblings Billy, Axel,

Amanda, and Augusta, and Augusta’s new husband Fred Malm, the visitors arriving by train from Eureka.

At the very least, the guests are known to have included Herman and Billy, because it was during that

holiday visit that Jack and his father and brother worked out the details of an arrangement that would

go on to have a profound impact on the destiny of the extended family: Herman and Billy agreed to move to

the farm and develop it on Jack’s behalf. Jack would pay their living expenses and do what he could to

help Billy acquire adjacent land. No longer would Jack and Annie’s acreage be left in the form of

alfalfa fields. Jack wanted it to become vineyard land, and that required a new level of commitment.

When the visit was over, Billy and Herman did not return north. They headed down to to Fresno County.

(For more about this, see Billy’s biography on this website.)

One of the improvements Billy and Herman

made in Reedley was to build a house. This meant Jack and Annie and their kids had a place to stay

whenever they visited their farm. Meanwhile in San Francisco their next dwelling was not actually a

house at all. Instead they lived on-site as resident caretakers of the Finnish Temperance Society Hall

at 425 Hoffman Avenue in the Noe Valley neighborhood, not far from the Upper-Market/Twin Peaks

neighborhood. (Shown at left are the caretakers’ quarters as they looked on the morning of 7 June

2013. Though more than a hundred years have passed since Jack and Annie lived there, the building is

still standing, if a bit worse for wear. The hall, which by contrast is in excellent condition, is

now the Latvian Lutheran Church of Northern California, the Finns having sold the structure to the

Latvians in the 1950s.) The couple would remain there into calendar year 1911,

making it one of their longest-term living situations in the city. They were undoubtedly already in

place by mid-1909, meaning that was where they were when Annie gave birth on the thirteenth of July to

Roy William Smeds. This was quite the celebratory event. Not only was there a new baby to brighten the

household, but he was the first grandson of Herman Smeds, the previous five grandchildren having all been

girls. The happy mood soon deteriorated into bleakness. To the horror of Jack and Annie, their little boy

suffered from a condition that make it next to impossible to keep his milk down. This is almost certain to

have been pyloric stenosis. This was an affliction that had Roy been born later in the century could have

been permanently corrected with surgery. In 1909, no dependable treatment was available. The baby was

unable to thrive. He died 4 October 1909 at less than three months of age.

One of the improvements Billy and Herman

made in Reedley was to build a house. This meant Jack and Annie and their kids had a place to stay

whenever they visited their farm. Meanwhile in San Francisco their next dwelling was not actually a

house at all. Instead they lived on-site as resident caretakers of the Finnish Temperance Society Hall

at 425 Hoffman Avenue in the Noe Valley neighborhood, not far from the Upper-Market/Twin Peaks

neighborhood. (Shown at left are the caretakers’ quarters as they looked on the morning of 7 June

2013. Though more than a hundred years have passed since Jack and Annie lived there, the building is

still standing, if a bit worse for wear. The hall, which by contrast is in excellent condition, is

now the Latvian Lutheran Church of Northern California, the Finns having sold the structure to the

Latvians in the 1950s.) The couple would remain there into calendar year 1911,

making it one of their longest-term living situations in the city. They were undoubtedly already in

place by mid-1909, meaning that was where they were when Annie gave birth on the thirteenth of July to

Roy William Smeds. This was quite the celebratory event. Not only was there a new baby to brighten the

household, but he was the first grandson of Herman Smeds, the previous five grandchildren having all been

girls. The happy mood soon deteriorated into bleakness. To the horror of Jack and Annie, their little boy

suffered from a condition that make it next to impossible to keep his milk down. This is almost certain to

have been pyloric stenosis. This was an affliction that had Roy been born later in the century could have

been permanently corrected with surgery. In 1909, no dependable treatment was available. The baby was

unable to thrive. He died 4 October 1909 at less than three months of age.

Jack had helped his siblings and father make it to America. Now came the time to do something for

Annie’s kin. In 1910, she and Jack offered fare and sponsorship to her sister Maria, who was then

seventeen. Maria warmed at once to the idea of immigrating, and in September she arrived. She lodged

briefly with Jack and Annie at the Temperance Society Hall, then found work as a live-in maid in the

city. Soon Annie was match-making, thinking Maria -- becoming known as Mary in the U.S. -- and Billy

Smeds would make a good pair. It took a year or so of persuasion, but her efforts were rewarded. A

wedding was held in January, 1912 at Jack and Annie’s home, which was by then in the Glen Park

neighborhood at 2 Mizpah Street. Soon Maria headed off to become a farm wife in Reedley.

That same year -- 1912 -- the vines on Jack and Annie’s land were mature enough to produce a

harvestable amount of fruit. Jack entered into a contractual agreement with Sun-Maid Raisin Company.

Billy followed suit. Payments from Sun-Maid made up a huge portion of the income both Smeds men and

their families earned for decades to come. As income from the land increased, Jack and Annie could

finally see the point looming when they would be able to leave San Francisco. In the meantime, they

moved one more time, the 2 Mizpah Street place being only a brief haven. They spent their final stretch

at 92 Eureka Street in the upper Castro near the Corona Heights neighborhood.

Jack (in center) and Annie (far left) in front of their Reedley house with neighbors Gust and

Sanna Laine and their young son Ruuno. The latter was born in the autumn of 1908, so clearly this is a

photograph captured some time in the early 1910s. Sadly, Ruuno would only survive to age thirteen.

In 1915, Jack and Annie settled in Reedley year-round. At about the same time, Karl Nordell sold his farm

at the corner of Holbrook Avenue and Peter Avenue to Jack and Annie. These developments go together, but

more research is needed to determine which caused the other. Did Jack and Annie resolve to move, and

make an offer to Karl? Or did Karl decide to sell, and Jack and Annie seized the opportunity? The purchase

of the Nordell farm resolved one of the main stumbling blocks that had been inhibiting the relocation. The

original farm was too small -- not to mention the fact

that it was where Billy and Mary were living. But Nordell’s acreage was plentiful. Jack could now earn

enough as a farmer to allow him to stop being a silversmith. He and Annie made plans to build a house of

their liking, Nordell never having put up anything meant for a family. (He had not, in fact, personally

stayed in Reedley for more than a few years after his January, 1905 arrival, leaving it to neighbors and/or

tenants to farm the acreage. The Laines seem to have provided the housing for those individuals.) However,

the best way to get that work done, given that Jack was going to do much of carpentry himself, was to move

first. This mean that Jack, Annie, Sylvia, and Lillian squeezed into the house with Billy, Mary, Roy,

and Alfred. And then to top it off,

newly-married Amanda Smeds and her husband Charles Strom decided they would rather initiate the

child-rearing phase of their lives in Reedley than in Eureka, and they crowded in as well until they

got set up on a farm of their own a few miles to the east. The irony was, soon the house had no family

members at all, because even Billy and Mary moved out, occupying a house on a farm immediately across

Holbrook Avenue.

Jack and Annie were no longer renters in a city, no longer living a geographically-split existence. They

were in their place at last. It was time to fill out the household, so they had one more baby. Son

Lawrence Jakob Smeds was born in the summer of 1917.

This biography, like a few others of the Smeds Family History website, is still a work in progress. The

material above is approaching its final form, but the material below, covering Jack’s life from 1915 onward,

is very incomplete. There will be quite a lot of additional text and at least two more photographs placed

here in the future.

Over the next four decades Jack was an active and prominent citizen of the Reedley-area community, and a

founding member and officer of the local Finnish Brotherhood chapter. (This was the case in spite of him

being a Finland Swede and is a mark of how much Jack adjusted to being an American Finn). The former

Nordell farm at Peter Avenue and Holbrook Avenue continued to be Jack and Annie’s place of residence until

their old age and death. After Fred and Katherine Tenhunen sold out to Billy and Mary -- the last part of

that transfer taking place in 1930 -- a continguous stretch of Kings River bluff farmland belonged to the

Smeds brothers, with A.A. Westerlund owning and occupying the acreage immediately south of Jack and

Annie’s house, and sharing a driveway with them. When Lawrence came

of age, the farm business became known as J.H. Smeds & Son, and issued fruit under a label they called

Anvil. (Meanwhile Billy and his sons formed William Smeds & Sons, issuing fruit under the Diamond “S”

label.) More land purchases in the middle years of the Twentieth Century expanded the holdings of J.H.

Smeds & Son, the main additions being the absorption of the Westerlund piece and the purchase of

a long stretch of riverbottom land often known among the family as “the Boy Scout camp” because Lawrence

Smeds hosted gatherings of the Boy Scouts along the river there for many years. The farm remained in

family hands until 1989, and even today a 1½-acre lot sub-divided out of the former Westerlund parcel

continues to be owned -- and resided upon -- by a great-granddaughter and her husband.

Jack died at home 17 March 1957. The event could easily be viewed as heralding the transition into a

new era. He had long been the reigning patriarch of the Smeds clan. Moreover, he was the first of the

Reedley-based members of his generation to pass away. (His siblings Axel, Augusta, and Mary and their

spouses had predeceased him, but they had made their homes elsewhere and therefore their absence did not

leave the same kind of void.) A.A. Westerlund would perish about

eighteen months later, and though Annie, Billy, and Mary Smeds and Amanda and Charlie Strom were still

around for a while after that, the younger family members were now the movers and shapers. The torch had

been passed.

Jack is second from the right with his hands in his jacket pockets in this photo from the 1950s of two

generations of Smeds Family farmers. His brother Billy is on the right. The young men are, from left to

right, nephews Alfred and Roy and son Lawrence. This photograph was taken for the local newspaper, the

Reedley Exponent, for an installment of their “Farmer of the Month” feature. The selection committee

could not decide which member of the Smeds clan they should honor, so the award went to all five as a

group.

Children of Jakob Herman Smeds

with Anna Gustava Rautiainen

Sylvia Alice

Smeds

Lillian Anna

Smeds

Roy William

Smeds

Lawrence Jakob

Smeds

To return to the Smeds Family History main page, click here.

Jakob Herman Smeds, eldest child of Jakob Herman Mattsson

Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs, was born 9 August 1881 on Section 1 of the ancestral Smeds

estate in Soklot, Finland. He grew up on that property. In mid-childhood his mother died. In the

wake of that tragedy, his paternal grandmother Lisa Jakobsdotter Pörkenäs Smeds moved into the home

to help her widower son bring up his kids. Lisa died in 1897, ending her tenure as surrogate mother.

Herman would thereafter get by with the assistance of his brother Erik’s wife Brita, who lived next

door. Brita’s contribution was essential to complete the raising of Jakob’s five younger siblings,

but Jakob’s own case was a little different. Weeks before his grandmother had passed away, Jakob had

already launched into the first phase of his independent life. He had not quite turned sixteen at

the time this occurred, but his father permitted it because Jakob went into a supervised situation

in the small city of Jakobstad as the live-in apprentice of a Mr. Bjorkman -- who was quite possibly

a relative. The training Jakob received during this period, which lasted a year and ten months,

proved to be critical to the destiny of his entire immediate family.

Jakob Herman Smeds, eldest child of Jakob Herman Mattsson

Smeds and Greta Mickelsdotter Fagernäs, was born 9 August 1881 on Section 1 of the ancestral Smeds

estate in Soklot, Finland. He grew up on that property. In mid-childhood his mother died. In the

wake of that tragedy, his paternal grandmother Lisa Jakobsdotter Pörkenäs Smeds moved into the home

to help her widower son bring up his kids. Lisa died in 1897, ending her tenure as surrogate mother.

Herman would thereafter get by with the assistance of his brother Erik’s wife Brita, who lived next

door. Brita’s contribution was essential to complete the raising of Jakob’s five younger siblings,

but Jakob’s own case was a little different. Weeks before his grandmother had passed away, Jakob had

already launched into the first phase of his independent life. He had not quite turned sixteen at

the time this occurred, but his father permitted it because Jakob went into a supervised situation

in the small city of Jakobstad as the live-in apprentice of a Mr. Bjorkman -- who was quite possibly

a relative. The training Jakob received during this period, which lasted a year and ten months,

proved to be critical to the destiny of his entire immediate family. Thanks to his trade skills, Jack was able within two or

three years to shift to a better-paying situation in San Francisco. His new employer was Shreve and

Company, a jewelry firm that had been founded during the Gold Rush (and still exists today). Shreve &

Company was a large-scale full-service company, fashioning not only decorative jewelry but silverware

and other household items, and Jack was tasked with generating a wide variety of merchandise. He was in

place by 1904. That was the year his brother Vilhelm (Billy) and sister Augusta

arrived. They would end up in Eureka, but it is unclear whether they joined Jack in Eureka, and then

Jack moved south, or if they joined Jack in San Francisco and, after a good visit with him there,

proceeded north to Eureka. (At right is a photograph of Jack and Billy taken in 1904-1906 at Shew’s

Pioneer Gallery, 520 Kearney Street, San Francisco. It may well have been taken in 1904 and suggests Jack

had in fact moved before Billy and Augusta arrived in the country. Having photographs taken upon arrival

to send back to relatives in Finland would have been a natural thing to do. The studio they chose had

quite a history. It had been founded by upstate New York native William Shew early in the Gold Rush --

about the same time, in fact, that Shreve & Company had been founded. Shew

had gone on to operate it for fifty years. By the time Jack and Billy posed, William Shew was recently

deceased and his young widow Anna Katherine Shew had inherited the business. An active photographer

herself, she may have been the very person who took this picture.)

Thanks to his trade skills, Jack was able within two or

three years to shift to a better-paying situation in San Francisco. His new employer was Shreve and

Company, a jewelry firm that had been founded during the Gold Rush (and still exists today). Shreve &

Company was a large-scale full-service company, fashioning not only decorative jewelry but silverware

and other household items, and Jack was tasked with generating a wide variety of merchandise. He was in

place by 1904. That was the year his brother Vilhelm (Billy) and sister Augusta

arrived. They would end up in Eureka, but it is unclear whether they joined Jack in Eureka, and then

Jack moved south, or if they joined Jack in San Francisco and, after a good visit with him there,

proceeded north to Eureka. (At right is a photograph of Jack and Billy taken in 1904-1906 at Shew’s

Pioneer Gallery, 520 Kearney Street, San Francisco. It may well have been taken in 1904 and suggests Jack

had in fact moved before Billy and Augusta arrived in the country. Having photographs taken upon arrival

to send back to relatives in Finland would have been a natural thing to do. The studio they chose had

quite a history. It had been founded by upstate New York native William Shew early in the Gold Rush --

about the same time, in fact, that Shreve & Company had been founded. Shew

had gone on to operate it for fifty years. By the time Jack and Billy posed, William Shew was recently

deceased and his young widow Anna Katherine Shew had inherited the business. An active photographer

herself, she may have been the very person who took this picture.)

In January, 1905, Laine and Nordell moved to Reedley,

hurriedly erecting a small cabin (shown at left) on Laine’s land that they would share while

developing their respective parcels. Others would arrive on the farms nearby and soon actual houses

started to appear. Jack, however, did not make his own move during this early period. He took a different

approach. He was earning steady money as a silversmith. As a farmer of undeveloped land, he knew he would

make nothing at all for at least a year. It is believed that he bought his first parcel at the same time

the others did, i.e. at the very end of 1904 or the very beginning of 1905 -- property records need to be

researched to be certain this is true -- but it would be another decade before he became an actual

resident of Reedley. He visited when he could. Otherwise he was to be found in in San Francisco, where

he continued to work at Shreve & Company, earning the funds he needed to pay down the mortgage. If he

did buy early, he probably did nothing during the first three calendar years of ownership beyond planting

alfalfa. This was a step Axel Wahren recommended as a way of fixing nitrogen in the soil and as a means

of generating some quick cash. Wahren had cautioned that skipping such a step and immediately planting

vineyards or orchards would leave impatient farmers with empty pockets just when they needed to make

capital improvements, and in the long run harm the vitality of their trees and vines. Alfalfa was a simple

crop suitable for an absentee farmer to grow. When hay-cutting time rolled around, hired workers could

handle the job just fine. Jack knew he could depend on the good will of neighbors like Nordell, Laine,

and Westerlund to serve as his intermediaries in finding customers for his crop, and keep him from being

cheated. Fred Tenhunen did the same, remaining in Berkeley until 1913. (And then Fred, as it turns out,

decided he wasn’t cut out to be a farmer after all. He and his family stayed in Reedley only seven or

eight years. They left in the early 1920s for Oakland, where Fred resumed his jewelry career. He

sold his farm to Billy Smeds in 1930.)

In January, 1905, Laine and Nordell moved to Reedley,

hurriedly erecting a small cabin (shown at left) on Laine’s land that they would share while

developing their respective parcels. Others would arrive on the farms nearby and soon actual houses

started to appear. Jack, however, did not make his own move during this early period. He took a different

approach. He was earning steady money as a silversmith. As a farmer of undeveloped land, he knew he would

make nothing at all for at least a year. It is believed that he bought his first parcel at the same time

the others did, i.e. at the very end of 1904 or the very beginning of 1905 -- property records need to be

researched to be certain this is true -- but it would be another decade before he became an actual

resident of Reedley. He visited when he could. Otherwise he was to be found in in San Francisco, where

he continued to work at Shreve & Company, earning the funds he needed to pay down the mortgage. If he

did buy early, he probably did nothing during the first three calendar years of ownership beyond planting

alfalfa. This was a step Axel Wahren recommended as a way of fixing nitrogen in the soil and as a means

of generating some quick cash. Wahren had cautioned that skipping such a step and immediately planting

vineyards or orchards would leave impatient farmers with empty pockets just when they needed to make

capital improvements, and in the long run harm the vitality of their trees and vines. Alfalfa was a simple

crop suitable for an absentee farmer to grow. When hay-cutting time rolled around, hired workers could

handle the job just fine. Jack knew he could depend on the good will of neighbors like Nordell, Laine,

and Westerlund to serve as his intermediaries in finding customers for his crop, and keep him from being

cheated. Fred Tenhunen did the same, remaining in Berkeley until 1913. (And then Fred, as it turns out,

decided he wasn’t cut out to be a farmer after all. He and his family stayed in Reedley only seven or

eight years. They left in the early 1920s for Oakland, where Fred resumed his jewelry career. He

sold his farm to Billy Smeds in 1930.)

Throughout their years in the Bay Area, Jack and Annie

always rented their living quarters -- the Fresno County farm being the only real estate they owned -- but

probably no period was as tenuous in terms of personal circumstances as what they experienced during 1906.

Years later Annie would sometimes mention that they lived in a tent during this time. Whether this was

while they were in Berkeley, or refers to their time in San Francisco after their move back, is not

clear. However, by the end of the calendar year their situation was again secure. And

just in time, too, because they had visitors. Jack was now a naturalized citizen, having wasted no time

in taking that step. He was able to serve as a sponsor for those immediate family members who had yet to

come over from Finland. By now there were only three left -- his father and his youngest siblings Axel and

Amanda, his sister Maria having already crossed the Atlantic in 1905, only to meet a man on the voyage

who proposed to her and took her to live as his wife in New Hampshire. Herman, Axel, and Amanda are known

to have disembarked from the liner Ivernia 20 December 1906 in Boston. A long cross-continental

train trip followed, which probably chewed up the remainder of December. But in early 1907, Jack and

Annie welcomed the travellers at their apartment on 28th Street, just down the hill to the immediate

west of Bernal Heights, not far from the place they had occupied before the earthquake. The newcomers may

have lingered as late as January 17th, in which case they were on hand to witness the arrival of Jack and

Annie’s second child, their daughter Lillian Anna Smeds. Soon, though, Herman, Axel, and Amanda went on

to Eureka, just as Billy and Augusta had done in 1904. (In the image at right, Billy is on the left,

Jack on the right, and their father is in the middle. This picture may have been taken shortly before

Jack left Finland. If not, it was taken in early 1907. Judging by how adolescent Billy appears, the earlier

date is probably the correct one.)

Throughout their years in the Bay Area, Jack and Annie

always rented their living quarters -- the Fresno County farm being the only real estate they owned -- but

probably no period was as tenuous in terms of personal circumstances as what they experienced during 1906.

Years later Annie would sometimes mention that they lived in a tent during this time. Whether this was

while they were in Berkeley, or refers to their time in San Francisco after their move back, is not

clear. However, by the end of the calendar year their situation was again secure. And

just in time, too, because they had visitors. Jack was now a naturalized citizen, having wasted no time

in taking that step. He was able to serve as a sponsor for those immediate family members who had yet to

come over from Finland. By now there were only three left -- his father and his youngest siblings Axel and

Amanda, his sister Maria having already crossed the Atlantic in 1905, only to meet a man on the voyage

who proposed to her and took her to live as his wife in New Hampshire. Herman, Axel, and Amanda are known

to have disembarked from the liner Ivernia 20 December 1906 in Boston. A long cross-continental

train trip followed, which probably chewed up the remainder of December. But in early 1907, Jack and

Annie welcomed the travellers at their apartment on 28th Street, just down the hill to the immediate

west of Bernal Heights, not far from the place they had occupied before the earthquake. The newcomers may

have lingered as late as January 17th, in which case they were on hand to witness the arrival of Jack and

Annie’s second child, their daughter Lillian Anna Smeds. Soon, though, Herman, Axel, and Amanda went on

to Eureka, just as Billy and Augusta had done in 1904. (In the image at right, Billy is on the left,

Jack on the right, and their father is in the middle. This picture may have been taken shortly before

Jack left Finland. If not, it was taken in early 1907. Judging by how adolescent Billy appears, the earlier

date is probably the correct one.) One of the improvements Billy and Herman

made in Reedley was to build a house. This meant Jack and Annie and their kids had a place to stay

whenever they visited their farm. Meanwhile in San Francisco their next dwelling was not actually a

house at all. Instead they lived on-site as resident caretakers of the Finnish Temperance Society Hall

at 425 Hoffman Avenue in the Noe Valley neighborhood, not far from the Upper-Market/Twin Peaks

neighborhood. (Shown at left are the caretakers’ quarters as they looked on the morning of 7 June

2013. Though more than a hundred years have passed since Jack and Annie lived there, the building is

still standing, if a bit worse for wear. The hall, which by contrast is in excellent condition, is

now the Latvian Lutheran Church of Northern California, the Finns having sold the structure to the

Latvians in the 1950s.) The couple would remain there into calendar year 1911,

making it one of their longest-term living situations in the city. They were undoubtedly already in

place by mid-1909, meaning that was where they were when Annie gave birth on the thirteenth of July to

Roy William Smeds. This was quite the celebratory event. Not only was there a new baby to brighten the

household, but he was the first grandson of Herman Smeds, the previous five grandchildren having all been

girls. The happy mood soon deteriorated into bleakness. To the horror of Jack and Annie, their little boy

suffered from a condition that make it next to impossible to keep his milk down. This is almost certain to

have been pyloric stenosis. This was an affliction that had Roy been born later in the century could have

been permanently corrected with surgery. In 1909, no dependable treatment was available. The baby was

unable to thrive. He died 4 October 1909 at less than three months of age.

One of the improvements Billy and Herman

made in Reedley was to build a house. This meant Jack and Annie and their kids had a place to stay

whenever they visited their farm. Meanwhile in San Francisco their next dwelling was not actually a

house at all. Instead they lived on-site as resident caretakers of the Finnish Temperance Society Hall

at 425 Hoffman Avenue in the Noe Valley neighborhood, not far from the Upper-Market/Twin Peaks

neighborhood. (Shown at left are the caretakers’ quarters as they looked on the morning of 7 June

2013. Though more than a hundred years have passed since Jack and Annie lived there, the building is

still standing, if a bit worse for wear. The hall, which by contrast is in excellent condition, is

now the Latvian Lutheran Church of Northern California, the Finns having sold the structure to the

Latvians in the 1950s.) The couple would remain there into calendar year 1911,

making it one of their longest-term living situations in the city. They were undoubtedly already in

place by mid-1909, meaning that was where they were when Annie gave birth on the thirteenth of July to

Roy William Smeds. This was quite the celebratory event. Not only was there a new baby to brighten the

household, but he was the first grandson of Herman Smeds, the previous five grandchildren having all been

girls. The happy mood soon deteriorated into bleakness. To the horror of Jack and Annie, their little boy

suffered from a condition that make it next to impossible to keep his milk down. This is almost certain to

have been pyloric stenosis. This was an affliction that had Roy been born later in the century could have

been permanently corrected with surgery. In 1909, no dependable treatment was available. The baby was

unable to thrive. He died 4 October 1909 at less than three months of age.