James Sutton Branson

James Sutton Branson, son of Alvin Thorpe Branson and Mary

Eliza Simmons and second of their five children, was born 8 July 1886 at Silver Lead Mine, Mariposa

County, CA, where Alvin was then employed as a miner. The site was near the still-extant town of Hornitos

and even nearer “Grasshopper Ranch,” the longterm home of grandparents John and Martha Branson.

James was given his middle name in honor of Charles Alonzo Sutton, who along with Isaac Paulton had

accompanied John Branson on the wagon-trail journey out west as 49ers in the Gold Rush.

James Sutton Branson, son of Alvin Thorpe Branson and Mary

Eliza Simmons and second of their five children, was born 8 July 1886 at Silver Lead Mine, Mariposa

County, CA, where Alvin was then employed as a miner. The site was near the still-extant town of Hornitos

and even nearer “Grasshopper Ranch,” the longterm home of grandparents John and Martha Branson.

James was given his middle name in honor of Charles Alonzo Sutton, who along with Isaac Paulton had

accompanied John Branson on the wagon-trail journey out west as 49ers in the Gold Rush.

James -- Jim -- grew up amid the mining culture of the Mother Lode and thought of himself as a miner so

completely he never could bring himself to pursue any other lifestyle for long, even though mining never

brought him the sort of rewards his grandfather had enjoyed. John Branson emerged from his mining career

as a gentleman landowner and pillar of his community. By contrast, James Sutton Branson had little positive

impact on society. This lack of success and thwarted ambition had a telling effect on the course of Jim’s

life. He found it impossible to sustain his marriages, and often drowned his sorrows in alcohol.

Alvin Branson ranged widely throughout Mariposa County during the years Jim was growing up, working at

Washington Mine, Mount Gaines Mine, Mt. Ophir Mine, as well as trying to get lucky at various placer

mining claims in tandem with partners Alonzo Diah Johnson (his brother-in-law) and Samuel Tippett.

Sometimes Alvin’s role was that of a common miner, but whenever he could he took skilled jobs as a blacksmith,

machinist, or carpenter. He also tried at least one non-mining gig when for two years (1892 and

1893), he grew crops at El Portal and then transported this food along with other supplies by pack mules

to the hotel in Yosemite Valley. Jim therefore grew up in several different locales. However, aside from

the two years in El Portal, there were just three main spots that regularly served as the family’s home

base. Only one of these spots was owned by Jim’s parents. That one was their cabin at Exchequer, where Alvin

spent some of each year digging the trench and tunnel of his so-called Last Chance Mine, hoping in vain for

it to produce a meaningful amount of gold. When they weren’t there, the family stayed with Jim’s grandparents

at Grasshopper Ranch or rented a house in Mariposa from the Gann family, the house probably consisting of the

extra home of rancher Elias Newton Gann, who lived mainly on his property in Whiterock precinct. (If the house

the Bransons rented did not belong to Elias Gann, it belonged to

one of Elias’s sons.) When the family was at Grasshopper Ranch, Jim attended Quartzburg School. When in

Mariposa, he attended Mariposa Elementary. Jim apparently did not think much of being forced to get

an education, and did not complete the eighth grade. Letters written by him survive to show he

could handle reading and writing just fine if he wanted to -- but he didn’t much want to. He was by no

means the only Branson of his generation to quit school early, though some, such as his first cousins

Eldridge, Ernest, and Gertie Branson, did finally finish eighth grade at Quartzburg School in 1909 when

they were eighteen, probably at the insistence of Jim’s aunt, Ella Geary Branson (the mother of Ernest and

Eldridge).

Over the years, Jim got to know a local girl,

Mary Ethel Harrigan. They may have first met in Hornitos, where her mother, Nellie M. Robinson Harrigan, was

the co-proprietress of the Hornitos Hotel for an interval in the late 1890s, working in tandem with her

sister-in-law Carrie Robinson, the wife of James B. Robinson, who had purchased the hotel. (James Robinson

operated the stage line while leaving the hotel management to his wife and sister.) Ethel, as she was called,

is known to have been a childhood friend of Jim’s first cousins Alex Branson and Inez Branson, the youngest

children of Thomas Henry Ousley Branson of Hornitos. Ethel also had a connection to Jim through

the Ganns. Her uncle, Frank D. Robinson, had been married to Elias Newton Gann’s daughter Mary Edith Gann

for a few years right at the turn of the century, when Jim was a teenager. However, Jim and Ethel were

probably bound to cross paths no matter what the family connections might be, due to the sheer proximity of

their homes. In the period from 1900 to 1908, Ethel lived mainly at her grandparents’ ranch in the Snelling

precinct of Merced County, which was just downstream along the Merced River from the Bransons’ cabin at

Exchequer.

Over the years, Jim got to know a local girl,

Mary Ethel Harrigan. They may have first met in Hornitos, where her mother, Nellie M. Robinson Harrigan, was

the co-proprietress of the Hornitos Hotel for an interval in the late 1890s, working in tandem with her

sister-in-law Carrie Robinson, the wife of James B. Robinson, who had purchased the hotel. (James Robinson

operated the stage line while leaving the hotel management to his wife and sister.) Ethel, as she was called,

is known to have been a childhood friend of Jim’s first cousins Alex Branson and Inez Branson, the youngest

children of Thomas Henry Ousley Branson of Hornitos. Ethel also had a connection to Jim through

the Ganns. Her uncle, Frank D. Robinson, had been married to Elias Newton Gann’s daughter Mary Edith Gann

for a few years right at the turn of the century, when Jim was a teenager. However, Jim and Ethel were

probably bound to cross paths no matter what the family connections might be, due to the sheer proximity of

their homes. In the period from 1900 to 1908, Ethel lived mainly at her grandparents’ ranch in the Snelling

precinct of Merced County, which was just downstream along the Merced River from the Bransons’ cabin at

Exchequer.

In some ways Jim and Ethel were an accident waiting to happen. Jim kept to a bachelor existence, working

hard and then playing hard in the saloons of the county. Ethel was a teenager cursed with a lack of

sufficient supervision. Her mother Nellie would come to be remembered as a cheerul, nurturant,

always-there-for-her-family sort of person, one who in later years would make a career of caring for

people as a nurse, but due to circumstances beyond her control she was not always available to keep an eye

on Ethel. Nellie was in her mid-thirties when her daughter and Jim became an item. Her story up to that

point is as follows: Part of a pioneering family of Snelling, Nellie as a fourteen-year-old student caught

the attention of the young schoolmaster of Eden School, Joseph Thomas Harrigan. This led to three years of

long-distance courtship by correspondence until finally, at seventeen, Nellie received a proposal from

Joseph. She married him and made a home with him in San Francisco, quickly producing two children, Mary

Ethel, born 2 May 1892, and Benjamin, born in the fall of 1893. (Shown above right is Nellie Robinson

Harrigan and her children in about 1900.) When Benjamin was no more than a year old, Nellie left her

husband. Later her granddaughter Melba would report that Nellie had left over “religious differences,”

but it is plain this was putting a mild face on what must have been an incredibly stressful set of

circumstances. Joseph was mentally unstable. By the end of the decade he was institutionalized, first in

Napa State Hospital and then in Agnew’s in Santa Clara County. He would spend most of the last fifteen

years of his life as an inmate. Though still undiagnosed as insane while with Nellie, he must have been

demonstrating so many signs of his problems that she believed it best for herself and her children to

leave him. She returned to her parents, William Robinson and Melissa Yonker Robinson, at their Snelling

ranch, staying there off and on over the next decade or so when she wasn’t doing such things as helping to

run the Hornitos Hotel. She would never marry again. Once probably struck her as plenty, given how hard it was

to divorce Joseph. She finally initiated the divorce in 1900, after he had been institutionalized. The case

took two years to proceed through the court system because the Merced County judge who first ruled on her

plea decided that because Joseph was insane, he could not mount a legal defense against the divorce and

therefore it was unfair to grant it to Nellie. She finally won free in 1902 when the California Supreme

Court reversed the lower court ruling with a precedent-setting decision.

As Ethel entered her teens, Nellie was often so busy trying to earn a living for her family as a single

mother that Ethel had too much freedom to get into trouble. The trouble was the predictable kind -- in the

spring of 1908, still a few weeks shy of turning sixteen years of age, she became pregnant by Jim. When

Nellie Harrigan and Alvin and Mary Branson discovered they were to be grandparents, they hastily

arranged for a wedding, which took place 25 July 1908 in Stockton, San Joaquin County, CA. In later years

the date would be adjusted to April in family genealogies to make it appear that the couple’s daughter,

Melba Arlyne Branson, whose birth occurred 26 January 1909 at the Gann rental house in Mariposa, had come

into the world nine months after the marriage had begun.

Throughout many families over many generations,

marriages had been initiated suddenly due to the pregnancy of the bride and nevertheless led to strong,

lifelong unions and big, happy families. But in the case of James and Ethel, there was probably never much

hope that it would

work out. Jim didn’t have a nickel to his name and wasn’t really prepared to be a father. However, for

about two years, the couple “gave it a go.” Jim and his father began gathering lumber beside the Exchequer

cabin in anticipation of building a neighboring shack for Jim and Ethel and Melba. Meanwhile, Alvin and

Mary boarded their new daughter-in-law and grandchild in their existing homes -- be those homes in Mariposa

or at Quartzburg or at Exchequer. (The Exchequer house is shown at left during the brief period

James and Ethel were a couple.) In some ways Ethel may have shared more of a bond with her in-laws

during this 1908-1910 phase than with her own husband. In the second half of the 1910 the couple

threw in the towel. The formal divorce may have taken a bit longer, but they ceased living together

that year. Ethel went on to marry Marion Bennett in 1913. They moved to Oakland, Alameda County, CA, where

Marion became an ice deliveryman. Ethel and Marion had one child, Marvin A. Bennett, born 24 September

1915. Ethel died 16 May 1917 of complications from a secret abortion she had undergone a week before in

San Francisco (a secret in the sense that her husband had not been aware

she was pregnant, and secret in the sense that abortions were illegal at the time). The one lasting

legacy of Ethel’s impact on Jim’s life was not the brief interval she spent as his wife, but from

her role in producing Melba, who would remain well-connected to her Branson kinfolk for all of

her long life.

Throughout many families over many generations,

marriages had been initiated suddenly due to the pregnancy of the bride and nevertheless led to strong,

lifelong unions and big, happy families. But in the case of James and Ethel, there was probably never much

hope that it would

work out. Jim didn’t have a nickel to his name and wasn’t really prepared to be a father. However, for

about two years, the couple “gave it a go.” Jim and his father began gathering lumber beside the Exchequer

cabin in anticipation of building a neighboring shack for Jim and Ethel and Melba. Meanwhile, Alvin and

Mary boarded their new daughter-in-law and grandchild in their existing homes -- be those homes in Mariposa

or at Quartzburg or at Exchequer. (The Exchequer house is shown at left during the brief period

James and Ethel were a couple.) In some ways Ethel may have shared more of a bond with her in-laws

during this 1908-1910 phase than with her own husband. In the second half of the 1910 the couple

threw in the towel. The formal divorce may have taken a bit longer, but they ceased living together

that year. Ethel went on to marry Marion Bennett in 1913. They moved to Oakland, Alameda County, CA, where

Marion became an ice deliveryman. Ethel and Marion had one child, Marvin A. Bennett, born 24 September

1915. Ethel died 16 May 1917 of complications from a secret abortion she had undergone a week before in

San Francisco (a secret in the sense that her husband had not been aware

she was pregnant, and secret in the sense that abortions were illegal at the time). The one lasting

legacy of Ethel’s impact on Jim’s life was not the brief interval she spent as his wife, but from

her role in producing Melba, who would remain well-connected to her Branson kinfolk for all of

her long life.

Jim had little to do with Melba’s upbringing. The girl was raised mainly by Nellie Robinson after the

untimely death of her mother. (The same was true of Melba’s half-brother Melvin for a couple of years,

but in 1919 Marion Bennett remarried, at which point he took back custody of his son.) Jim carried on

almost as if he had been a bachelor all along. This was to his detriment. His lifestyle caught

up with him. On the ninth of February, 1917, he brandished a pistol in the face of Hornitos saloonkeeper

George A. Latchaw and threatened the man’s life. While no shots were fired, Jim was arrested for assault

with a deadly weapon. Just what set Jim off is not clear, but is easy to imagine. Latchaw had probably

refused to serve Jim, either because he was too drunk, too unruly, or because he had not paid his tab.

Whatever the reason, Jim had gone too far, and spent the next five days in the county jail before his

aunt Annie Flint and his first cousin John Joseph Branson put up the bail money. Benjamin Steele Wilson,

a special friend of Jim’s aunt Mary Jane Branson, agreed to step in as defense attorney, and succeeded

in arranging a deal with the prosecutor. Jim pled guilty to the charge 2 April 1917 in court

in the town of Mariposa (in a courthouse Jim had been able to see from the front stoop of the Gann house

in his childhood). The judge was Joseph J. Trabucco, an old friend of the Branson clan, who a few days later

handed down a ruling of a suspended sentence. Jim was left at liberty as long as he kept his nose clean.

Unfortunately, some six weeks later, Jim violated his probation, apparently by getting into a saloon brawl

in Groveland, Tuolumne County, CA and getting himself arrested by the authorities there. The timing of the

incident is significant. Jim had probably just received a telegram about the death of his ex-wife and the

news had put him into a black and bitter mood. Mariposa County Sheriff Walter Scott Farnsworth fetched him

from the Tuolumne County jail and brought him back to face Judge Trabucco at a hearing held in Mariposa 21

May 1917. Ben Wilson was present, but there wasn’t much he could do. The judge issued the order to send

Jim to San Quentin prison. Sheriff Farnsworth delivered him there on the 23rd. Jim served just over twelve

months of a fifteen-month sentence. He was discharged 8 June 1918. He happened to be there 5 June 1917 when

he filed his draft registration card, and that document therefore describes his occupation as “inmate.” (One

of the incredible aspects of the 1917-18 draft was that essentially all men between the ages of eighteen

and forty-six were required to register, even if they were ineligible to actually enter the military, as

in the case of foreigners, cripples, and convicts.)

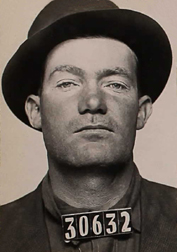

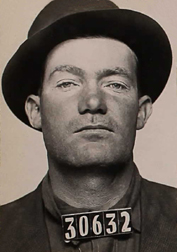

(Shown at right is the photo that was attached to

Jim’s prison file, taken upon his entry in 1917.) Once free, Jim stuck with what he knew, which was

mining. By then, Mariposa County’s mining industry had crashed, so he found (or at least searched for) work

in many scattered locales. For about a year and a half he seems to have been based at the northern end of

the Mother Lode. He may have worked with Clyde Leroy Miller, who married Jim’s older sister Maude in 1919.

Clyde is known to have worked in Placer County in the autumn of 1918. The 1920 census (effective date January

1st) shows Jim in Grass Valley, Nevada County, CA, living in a miners’ boarding house. However, shortly

after that record was made, Jim went to Gila County, AZ and began working as a copper miner -- eventually

if not immediately as a “top lander” for Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company at its site two miles outside

the village of Globe. Soon after his arrival he became acquainted with divorcée Carrie Hays, and married her

12 June 1920 in Globe after at most a few months of courtship.

(Shown at right is the photo that was attached to

Jim’s prison file, taken upon his entry in 1917.) Once free, Jim stuck with what he knew, which was

mining. By then, Mariposa County’s mining industry had crashed, so he found (or at least searched for) work

in many scattered locales. For about a year and a half he seems to have been based at the northern end of

the Mother Lode. He may have worked with Clyde Leroy Miller, who married Jim’s older sister Maude in 1919.

Clyde is known to have worked in Placer County in the autumn of 1918. The 1920 census (effective date January

1st) shows Jim in Grass Valley, Nevada County, CA, living in a miners’ boarding house. However, shortly

after that record was made, Jim went to Gila County, AZ and began working as a copper miner -- eventually

if not immediately as a “top lander” for Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company at its site two miles outside

the village of Globe. Soon after his arrival he became acquainted with divorcée Carrie Hays, and married her

12 June 1920 in Globe after at most a few months of courtship.

The speed with which the couple wed probably had to do with Carrie’s desire to link up with a breadwinner

figure for her three young sons Emory, Lynnie, and Johnnie (formally John William Emory Hays, Columbus

Franklin Hays, and John Risser Hays). The elder two were about to turn nine and six that summer, and Johnnie

was four. Practical aspects aside, the union was Jim’s big chance to settle in and “do it right.” Having

reached his early thirties, he had gained some perspective on life and must have grasped what the opportunity

represented. In Carrie, he seemed to have found the right match. She had lived among miners for many years

and had an understanding and respect for the profession. Moreover, she was a rooted-in sort of figure with

a support system in place and a familiarity with the locality. Born Caroline Emmaline McCord 11 May 1892

in Pawhuska, OK to parents William Morse McCord and Ida Adeline Simmons (no relation to the Simmons family

that Jim sprang from), she had been brought up from early childhood in Gila County on a ranch owned by her

stepfather Sampson Elam Boles, Jr. Now in the early 1920s, Ida and Elam still lived west of Globe, though

they had down-sized

after selling the ranch to celebrity author Zane Grey. Carrie had only recently become single again after

parting ways with first husband John Franklin Hays.

Unfortunately, Jim and Carrie’s marriage lasted only three to four years. She was not the sort of woman who

clung to a man she wasn’t pleased with. Toward the end of 1925 she wed Owen Spangler. That union likewise

did not endure, though it is unclear whether the brevity was caused by divorce, or was a consequence of Mr.

Spangler’s death. In 1938, Carrie wed John Wesley Howard, with whom she finally found lasting harmony. They

spent some of the early part of their union in Compton, CA before a return to Arizona. Widowed in 1958, Carrie

lingered in Gila County thereafter. She died 19 November 1977 in Globe. Her grave, which lies next to that of

John Howard, can be found at Pinal Cemetery, Central Heights, Gila County, AZ.

Jim would never be a husband or stepfather again. The only silver lining is that he was so footloose, he

could think big in terms of options, and for a period in the 1920s, was employed as a miner in Peru. This

circumstance lasted less than five years. It is apparent he was back in the United States in

the summer of 1928. The evidence is a surviving postcard Jim sent to his mother 12 June 1928 from La Grande,

OR. It begins, “We are three hundred miles above [i.e. east of] Portland headed for Idaho, then on into

Nevada. Be home this fall some time.” The reference to “we” means Jim was probably travelling with his

brother Ivan and sister-in-law Marion, who often took long trips through the western United States.

The 1930 census confirms that Jim was still a miner, though by now he had given up actually living in

the hills and had obtained a bed in a huge boarding facility in Stockton. This put him near his parents and

siblings, Stockton having become the home base of most of the Alvin Branson-Mary Simmons family starting

in 1914. As he proceeded into middle age and his health declined and his drinking (if possible) increased,

it was agreed that he was best off seeing as little of other people as possible. His brother Ivan had the

financial wherewithal to pay for his lodgings in a cabin back in the Hornitos area, so this arrangement was

made, and Jim spent much of the last fifteen years of his life dwelling there in more or less on-going

isolation. Jim died in Stockton 19 June 1945. His body was interred at Stockton Rural Cemetery next to

the remains of his mother and father. His brother Walter would eventually be buried there, filling the last

of the four graves purchased at the time of Alvin’s death. Nowadays the graves of his sister Maude and many

other members of the Branson clan can be found at Stockton Rural Cemetery, though not all in the same

section.

All in all, James Sutton Branson lived a lonely and unhappy life. In the early iterations of the writings

that would culminate in the book Bones of the Bransons, Ivan Branson composed a short biography and

then a commentary about Jim to explain why his brother would find it so hard to reach out to people and

evolve out of his circumstances. The latter is quoted here in full.

JAMES SUTTON BRANSON (1886-1945)

A commentary by his younger brother Ivan Branson, July 21, 1962

I believe it was Marc Anthony who said: “I come not to praise Caesar, but to bury him.”

So, before commenting upon the personality of my late and beloved brother, I wish to remind the reader of

the times in which we deal, for the “praises of yesterday have short echoes.”

In the eighteen eighties and nineties, many “second

generation” Native Sons were being born into an

economy and a way of life that by today’s standards beggars description. For almost a half-century GOLD

had been the mainstay of most California activity. With the depletion of the placers, and Congressional

action against hydraulic mining, only the richest of the small lode mines could operate. These, of course,

had but a single crop. When jobs in these mines did appear, the wages were from two to three dollars for

a 12-hour “shift,” usually in dripping wet shafts or drifts, and often amid clouds of silicon dust. Of

course there was freight to be hauled, and hay and grain to be grown for the horses to pull freight wagons,

and roads to be built and repaired, but little else to sustain commerce. Paydays were never more than

once a month, and frequently a mine would fail, and the employees be turned loose with two or three months’

back pay due them. I will not comment on the usual hardships of the times, such as grinding your own

coffee, or the hand-sawing of wood, etc., etc., these items are well known. Just to sum up the hard facts

in the mining country after the bloom was off, believe me it was plenty tough to find food and clothing and

transportation. Shelter wasn’t too good, either.

In the eighteen eighties and nineties, many “second

generation” Native Sons were being born into an

economy and a way of life that by today’s standards beggars description. For almost a half-century GOLD

had been the mainstay of most California activity. With the depletion of the placers, and Congressional

action against hydraulic mining, only the richest of the small lode mines could operate. These, of course,

had but a single crop. When jobs in these mines did appear, the wages were from two to three dollars for

a 12-hour “shift,” usually in dripping wet shafts or drifts, and often amid clouds of silicon dust. Of

course there was freight to be hauled, and hay and grain to be grown for the horses to pull freight wagons,

and roads to be built and repaired, but little else to sustain commerce. Paydays were never more than

once a month, and frequently a mine would fail, and the employees be turned loose with two or three months’

back pay due them. I will not comment on the usual hardships of the times, such as grinding your own

coffee, or the hand-sawing of wood, etc., etc., these items are well known. Just to sum up the hard facts

in the mining country after the bloom was off, believe me it was plenty tough to find food and clothing and

transportation. Shelter wasn’t too good, either.

Entertainment, as we know it today, just didn’t exist. The saloon (ladies not welcome) was the normal

forum for all who cared to socialize. Card games had to be the main indoor sport. Saturday night, of

course, there would be a dance, somewhere, in a lodge hall or school house, and it was a dull evening if

no fisticuffs developed.

In the family, James had quite a team. 44 first cousins in the Branson group [this counts four who are

actually siblings, not cousins], 20 more in the Simmons group.

Schooling? Well, it was popular not to finish grammar school.

Neighbors? There were still Yosemite Indians in the home town. One did not associate with them; at least

not intimately. Also there were original “Californios” -- grand Spanish people, but too often referred to

as “greasers” to be caught getting friendly with. And there were a few Chinese who failed to go back to

China with the Exclusion Proclamation; but these too were “low” people and not subject to friendship. Other

folk had to be left off the roster of friends because of “politics.” The Civil War had been “settled” with

Lee’s Surrender, but the bitterness had not yet been buried. (This paragraph requires careful reflection.

Ivan is certainly not condemning any of these groups, but portraying reasons why Jim may have felt he

was not supposed to bond with the people he was surrounded by. Other family members lived with

and even married native Americans and Californios, some lived with Chinese friends and thought so much

of them and their culture as to learn to speak Chinese. The Bransons may have been creatures of their

narrow-minded times, but on the whole were tolerant and loving people -- Jim was in the end responsible

for creating his own demons. What is fair to say is that he had many bad examples of bigotry around him in

old-time Mariposa County to give him an ample supply of excuses he could use to justify his personal

isolation.)

Except for his alcoholic problem, James was a most popular man, making friends quickly, and keeping them

always. He was sincere and energetic, fully honest, and a fine conversationalist. Naturally an outdoorsman,

loving to fish and hunt, and when not employed by miners or hay farmers, he prospected or worked mines for

himself or with partners; a way of life pursued by his father and his grandfather.

His travels included the western states, with a trip to Peru in the 1920s to mine for the Guggenheim

interests.

Most of his life was lived in California’s famous Mother Lode country. Among the mines and mining towns where

he received his mail were: Mariposa, Hornitos, Exchequer, Mount Bullion, Bear Valley, Jamestown, Sonora,

Plymouth, Soulsbyville, Tuolumne, Springfield, Downieville, Butler Creek.

His last years were spent mainly at his cabin in Hornitos. His early passing is attributed to lung

cancer, possibly induced by silicon dust from deep mining.

Child of James Sutton Branson with

Ethel Mary Harrigan

Melba Arlyne

Branson

For genealogical details, click on

Melba’s name.

To go back one generation, click here. To return

to the Branson/Ousley Family main page, click here.

James Sutton Branson, son of Alvin Thorpe Branson and Mary

Eliza Simmons and second of their five children, was born 8 July 1886 at Silver Lead Mine, Mariposa

County, CA, where Alvin was then employed as a miner. The site was near the still-extant town of Hornitos

and even nearer “Grasshopper Ranch,” the longterm home of grandparents John and Martha Branson.

James was given his middle name in honor of Charles Alonzo Sutton, who along with Isaac Paulton had

accompanied John Branson on the wagon-trail journey out west as 49ers in the Gold Rush.

James Sutton Branson, son of Alvin Thorpe Branson and Mary

Eliza Simmons and second of their five children, was born 8 July 1886 at Silver Lead Mine, Mariposa

County, CA, where Alvin was then employed as a miner. The site was near the still-extant town of Hornitos

and even nearer “Grasshopper Ranch,” the longterm home of grandparents John and Martha Branson.

James was given his middle name in honor of Charles Alonzo Sutton, who along with Isaac Paulton had

accompanied John Branson on the wagon-trail journey out west as 49ers in the Gold Rush. Over the years, Jim got to know a local girl,

Mary Ethel Harrigan. They may have first met in Hornitos, where her mother, Nellie M. Robinson Harrigan, was

the co-proprietress of the Hornitos Hotel for an interval in the late 1890s, working in tandem with her

sister-in-law Carrie Robinson, the wife of James B. Robinson, who had purchased the hotel. (James Robinson

operated the stage line while leaving the hotel management to his wife and sister.) Ethel, as she was called,

is known to have been a childhood friend of Jim’s first cousins Alex Branson and Inez Branson, the youngest

children of Thomas Henry Ousley Branson of Hornitos. Ethel also had a connection to Jim through

the Ganns. Her uncle, Frank D. Robinson, had been married to Elias Newton Gann’s daughter Mary Edith Gann

for a few years right at the turn of the century, when Jim was a teenager. However, Jim and Ethel were

probably bound to cross paths no matter what the family connections might be, due to the sheer proximity of

their homes. In the period from 1900 to 1908, Ethel lived mainly at her grandparents’ ranch in the Snelling

precinct of Merced County, which was just downstream along the Merced River from the Bransons’ cabin at

Exchequer.

Over the years, Jim got to know a local girl,

Mary Ethel Harrigan. They may have first met in Hornitos, where her mother, Nellie M. Robinson Harrigan, was

the co-proprietress of the Hornitos Hotel for an interval in the late 1890s, working in tandem with her

sister-in-law Carrie Robinson, the wife of James B. Robinson, who had purchased the hotel. (James Robinson

operated the stage line while leaving the hotel management to his wife and sister.) Ethel, as she was called,

is known to have been a childhood friend of Jim’s first cousins Alex Branson and Inez Branson, the youngest

children of Thomas Henry Ousley Branson of Hornitos. Ethel also had a connection to Jim through

the Ganns. Her uncle, Frank D. Robinson, had been married to Elias Newton Gann’s daughter Mary Edith Gann

for a few years right at the turn of the century, when Jim was a teenager. However, Jim and Ethel were

probably bound to cross paths no matter what the family connections might be, due to the sheer proximity of

their homes. In the period from 1900 to 1908, Ethel lived mainly at her grandparents’ ranch in the Snelling

precinct of Merced County, which was just downstream along the Merced River from the Bransons’ cabin at

Exchequer. Throughout many families over many generations,

marriages had been initiated suddenly due to the pregnancy of the bride and nevertheless led to strong,

lifelong unions and big, happy families. But in the case of James and Ethel, there was probably never much

hope that it would

work out. Jim didn’t have a nickel to his name and wasn’t really prepared to be a father. However, for

about two years, the couple “gave it a go.” Jim and his father began gathering lumber beside the Exchequer

cabin in anticipation of building a neighboring shack for Jim and Ethel and Melba. Meanwhile, Alvin and

Mary boarded their new daughter-in-law and grandchild in their existing homes -- be those homes in Mariposa

or at Quartzburg or at Exchequer. (The Exchequer house is shown at left during the brief period

James and Ethel were a couple.) In some ways Ethel may have shared more of a bond with her in-laws

during this 1908-1910 phase than with her own husband. In the second half of the 1910 the couple

threw in the towel. The formal divorce may have taken a bit longer, but they ceased living together

that year. Ethel went on to marry Marion Bennett in 1913. They moved to Oakland, Alameda County, CA, where

Marion became an ice deliveryman. Ethel and Marion had one child, Marvin A. Bennett, born 24 September

1915. Ethel died 16 May 1917 of complications from a secret abortion she had undergone a week before in

San Francisco (a secret in the sense that her husband had not been aware

she was pregnant, and secret in the sense that abortions were illegal at the time). The one lasting

legacy of Ethel’s impact on Jim’s life was not the brief interval she spent as his wife, but from

her role in producing Melba, who would remain well-connected to her Branson kinfolk for all of

her long life.

Throughout many families over many generations,

marriages had been initiated suddenly due to the pregnancy of the bride and nevertheless led to strong,

lifelong unions and big, happy families. But in the case of James and Ethel, there was probably never much

hope that it would

work out. Jim didn’t have a nickel to his name and wasn’t really prepared to be a father. However, for

about two years, the couple “gave it a go.” Jim and his father began gathering lumber beside the Exchequer

cabin in anticipation of building a neighboring shack for Jim and Ethel and Melba. Meanwhile, Alvin and

Mary boarded their new daughter-in-law and grandchild in their existing homes -- be those homes in Mariposa

or at Quartzburg or at Exchequer. (The Exchequer house is shown at left during the brief period

James and Ethel were a couple.) In some ways Ethel may have shared more of a bond with her in-laws

during this 1908-1910 phase than with her own husband. In the second half of the 1910 the couple

threw in the towel. The formal divorce may have taken a bit longer, but they ceased living together

that year. Ethel went on to marry Marion Bennett in 1913. They moved to Oakland, Alameda County, CA, where

Marion became an ice deliveryman. Ethel and Marion had one child, Marvin A. Bennett, born 24 September

1915. Ethel died 16 May 1917 of complications from a secret abortion she had undergone a week before in

San Francisco (a secret in the sense that her husband had not been aware

she was pregnant, and secret in the sense that abortions were illegal at the time). The one lasting

legacy of Ethel’s impact on Jim’s life was not the brief interval she spent as his wife, but from

her role in producing Melba, who would remain well-connected to her Branson kinfolk for all of

her long life. (Shown at right is the photo that was attached to

Jim’s prison file, taken upon his entry in 1917.) Once free, Jim stuck with what he knew, which was

mining. By then, Mariposa County’s mining industry had crashed, so he found (or at least searched for) work

in many scattered locales. For about a year and a half he seems to have been based at the northern end of

the Mother Lode. He may have worked with Clyde Leroy Miller, who married Jim’s older sister Maude in 1919.

Clyde is known to have worked in Placer County in the autumn of 1918. The 1920 census (effective date January

1st) shows Jim in Grass Valley, Nevada County, CA, living in a miners’ boarding house. However, shortly

after that record was made, Jim went to Gila County, AZ and began working as a copper miner -- eventually

if not immediately as a “top lander” for Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company at its site two miles outside

the village of Globe. Soon after his arrival he became acquainted with divorcée Carrie Hays, and married her

12 June 1920 in Globe after at most a few months of courtship.

(Shown at right is the photo that was attached to

Jim’s prison file, taken upon his entry in 1917.) Once free, Jim stuck with what he knew, which was

mining. By then, Mariposa County’s mining industry had crashed, so he found (or at least searched for) work

in many scattered locales. For about a year and a half he seems to have been based at the northern end of

the Mother Lode. He may have worked with Clyde Leroy Miller, who married Jim’s older sister Maude in 1919.

Clyde is known to have worked in Placer County in the autumn of 1918. The 1920 census (effective date January

1st) shows Jim in Grass Valley, Nevada County, CA, living in a miners’ boarding house. However, shortly

after that record was made, Jim went to Gila County, AZ and began working as a copper miner -- eventually

if not immediately as a “top lander” for Inspiration Consolidated Copper Company at its site two miles outside

the village of Globe. Soon after his arrival he became acquainted with divorcée Carrie Hays, and married her

12 June 1920 in Globe after at most a few months of courtship. In the eighteen eighties and nineties, many “second

generation” Native Sons were being born into an

economy and a way of life that by today’s standards beggars description. For almost a half-century GOLD

had been the mainstay of most California activity. With the depletion of the placers, and Congressional

action against hydraulic mining, only the richest of the small lode mines could operate. These, of course,

had but a single crop. When jobs in these mines did appear, the wages were from two to three dollars for

a 12-hour “shift,” usually in dripping wet shafts or drifts, and often amid clouds of silicon dust. Of

course there was freight to be hauled, and hay and grain to be grown for the horses to pull freight wagons,

and roads to be built and repaired, but little else to sustain commerce. Paydays were never more than

once a month, and frequently a mine would fail, and the employees be turned loose with two or three months’

back pay due them. I will not comment on the usual hardships of the times, such as grinding your own

coffee, or the hand-sawing of wood, etc., etc., these items are well known. Just to sum up the hard facts

in the mining country after the bloom was off, believe me it was plenty tough to find food and clothing and

transportation. Shelter wasn’t too good, either.

In the eighteen eighties and nineties, many “second

generation” Native Sons were being born into an

economy and a way of life that by today’s standards beggars description. For almost a half-century GOLD

had been the mainstay of most California activity. With the depletion of the placers, and Congressional

action against hydraulic mining, only the richest of the small lode mines could operate. These, of course,

had but a single crop. When jobs in these mines did appear, the wages were from two to three dollars for

a 12-hour “shift,” usually in dripping wet shafts or drifts, and often amid clouds of silicon dust. Of

course there was freight to be hauled, and hay and grain to be grown for the horses to pull freight wagons,

and roads to be built and repaired, but little else to sustain commerce. Paydays were never more than

once a month, and frequently a mine would fail, and the employees be turned loose with two or three months’

back pay due them. I will not comment on the usual hardships of the times, such as grinding your own

coffee, or the hand-sawing of wood, etc., etc., these items are well known. Just to sum up the hard facts

in the mining country after the bloom was off, believe me it was plenty tough to find food and clothing and

transportation. Shelter wasn’t too good, either.