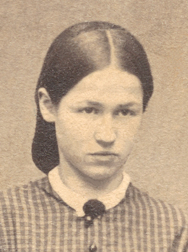

Jennie Edith Martin

Jennie Edith Martin,

fourth of the fourteen children of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, was born 1 November 1850 in

Martintown, Green County, WI, meaning that she was the first of Nathaniel and Hannah’s offspring to be

born after the family had become established in its longterm home.

Jennie Edith Martin,

fourth of the fourteen children of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, was born 1 November 1850 in

Martintown, Green County, WI, meaning that she was the first of Nathaniel and Hannah’s offspring to be

born after the family had become established in its longterm home.

Jennie grew to be about five foot, three or four inches in height. She had full lips, dark

brown eyes, and dark brown hair -- features that reappeared among her children and grandchildren. Like

most women of her generation she did not have a career

outside the home. She was handy and quick with a sewing machine. She played piano and melodeon.

(The details in this paragraph come from the notes of her granddaughter Sarah Jeanette Hodge. It

should be noted that Sarah was born well after Jennie’s death and therefore learned this

information indirectly.)

Jennie became a wife on 1 November 1868 -- her eighteenth

birthday. She was the first of Nathaniel and Hannah’s children to wed. The groom was Jacob Sylvester

Hodge, son of Daniel Freeman Hodge and Eliza Jane Bugh. Jacob had been born 18 June 1848 in Wyandot

County, OH at the end of a year during which his father, in partnership with Jacob’s namesake uncle

Jacob Bugh, had operated a ferry over the Sandusky River east of McCutchenville. The Bugh/Hodge clan

had relocated to southwestern Wisconsin in 1848 or 1849, and that was where Jacob had spent the bulk of

his early childhood. By the end of the 1860s, Jacob’s parents were living near Delavan, Faribault

County, MN, nearly two hundred miles west of Martintown -- what brought Jacob to Jennie’s neck

of the woods is therefore a bit of a puzzle.

The couple began their married lives as a farm family upon a

large parcel of land along the Pecatonica

River on the mill side just over the state line -- acreage which Jennie received as a dowry gift from

her parents. Technically, this meant they had an address of Winslow, Stephenson County, IL, though they

were more accurately residents of rural Martintown. In the summer of 1869 Jennie and Jacob became the

parents of Nathaniel M. Hodge, the very first grandchild of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, and the

first of several descendants to bear the patriarch’s given name. With a growing family, Jacob was eager

to bring in extra income, so he formed a partnership with Jennie’s brother Horatio Woodman Martin. The

two young men operated Martintown’s general store, which had been opened by J.W. Mitchell in 1869 and then

had been run by William Hodges, the original postmaster of the village. (William was not a relative of

Jacob -- one was a Hodges, the other a Hodge.)

The couple began their married lives as a farm family upon a

large parcel of land along the Pecatonica

River on the mill side just over the state line -- acreage which Jennie received as a dowry gift from

her parents. Technically, this meant they had an address of Winslow, Stephenson County, IL, though they

were more accurately residents of rural Martintown. In the summer of 1869 Jennie and Jacob became the

parents of Nathaniel M. Hodge, the very first grandchild of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, and the

first of several descendants to bear the patriarch’s given name. With a growing family, Jacob was eager

to bring in extra income, so he formed a partnership with Jennie’s brother Horatio Woodman Martin. The

two young men operated Martintown’s general store, which had been opened by J.W. Mitchell in 1869 and then

had been run by William Hodges, the original postmaster of the village. (William was not a relative of

Jacob -- one was a Hodges, the other a Hodge.)

The Hodge & Martin partnership did not last long, perhaps as little as two years (1871-1873). The birth

of daughter Agnes Leona Hodge occurred during that span. She was born in February, 1872. By no later

than 1875, Jennie and Jacob pulled up stakes. The 1 May 1875 Minnesota state census shows the couple had

by then reestablished themselves near Jacob’s parents in Delavan. The timing of their move strongly hints

that the general store failed. (There would of course continue to be a general store in operation in the

village during the rest of the 1870s and beyond, but it was operated by William Edwards and Watson

Wright.) The collapse of the business venture is likely to have been due to the Panic of 1873 and the

dissolution of a plan to bring a railroad line to Martintown. The U.S. and Europe would take many years

to fully recover from the economic downturn. The effect on Jacob Hodge seems to have been that he

completely lost faith in a career as a shopkeeper and additionally lost faith in Martintown as a place in

which he would prosper in any role. Once they left, the Hodges seem to have come back to Martintown on

only two occasions (as hinted at in an 1897 letter written by Nathaniel M. Hodge). One visit was in the

mid-1870s for a family Christmas gathering. The other time must have been for Jennie’s funeral.

Delavan was where Jennie gave birth to the remainder of her offspring. Third child Adrian Hodge was born

18 February 1876, but succumbed to scarlet fever less than three months later. Jennie was understandably

bereaved. To have some small memento of Adrian, she traced an outline of his hand onto a piece of paper

shortly after he died, and kept the drawing in the family Bible. The Bible, which later came into the

possession of daughter Agnes and was in Agnes’s home in San Francisco 18 April 1906, where it was destroyed

along with the house in the fire caused by the great earthquake.

The 1877 birth of fourth child Arthur Judson Hodge could be said to be the final joyous development in

Jennie’s life. Within a year or two at most, her mental stability deteriorated beyond repair. Perhaps the

stress of leaving her place of origin and birth family, losing a baby, and trying to hold together a

home of three surviving children was more than she could cope with. More likely, these factors merely

exposed an underlying

psychological fragility inherited from her father. Nathaniel Martin had suffered multiple episodes of

deranged behavior. In fact, the worst of these breakdowns was still relatively current -- 1878 -- resulting

in his incarceration within Mendota State Hospital for the Insane in Madison (Westport), Dane County, WI.

Jennie was soon committed to Mendota as well, even as Nathaniel was being released. The 1880 census shows her

as a resident there. (The enumerator put a mark in the column labelled “Insane” as part of Jennie’s entry.

Every person on that page is similarly categorized.) While she was being kept there, her spouse first took

refuge with his sister Mary Jane and brother-in-law Oscar Hathaway in Beetown, Grant County, WI. The

census shows him as part of that household. His toddler son Arthur was there as well, as were Mary Jane

and Oscar’s two children. However, Nathaniel Hodge and Agnes Leona Hodge are unaccounted for. Their

whereabouts in 1880 remains a mystery. It seems likely they were housed nearby with other Hodge relatives

who neglected to describe them as residents to the census enumerator.

Jennie apparently never left Mendota. She may have committed

suicide. Family lore says she drowned in Lake Mendota. However, the date of death was 28 February 1882. She

would not have been in the water for any legitimate reason such as a swimming party for the patients. At

that time of year in Wisconsin, no one goes swimming -- water temperatures are at best just above freezing.

If she went into the lake at all, it was by sneaking out of the hospital and using the water to help ensure

her death. An article in the 15 March 1882 edition of The Weekly Wisconsin of Milwaukee mentions an

investigation to put to rest “startling rumors” about her death, and that the result of said investigation

was that she had died of brain fever. This is unfortunately not definitive. If the asylum wanted to cover up

its own incompetence in letting Jennie escape her quarters and kill herself, they would have made sure an

investigation resulted in such a finding. Moreover, the family would have wanted such a finding to be

announced. Whatever the particulars, Jennie was dead at only age thirty-one. Her body was brought from Madison

to Martintown for burial in the family graveyard.

Jennie apparently never left Mendota. She may have committed

suicide. Family lore says she drowned in Lake Mendota. However, the date of death was 28 February 1882. She

would not have been in the water for any legitimate reason such as a swimming party for the patients. At

that time of year in Wisconsin, no one goes swimming -- water temperatures are at best just above freezing.

If she went into the lake at all, it was by sneaking out of the hospital and using the water to help ensure

her death. An article in the 15 March 1882 edition of The Weekly Wisconsin of Milwaukee mentions an

investigation to put to rest “startling rumors” about her death, and that the result of said investigation

was that she had died of brain fever. This is unfortunately not definitive. If the asylum wanted to cover up

its own incompetence in letting Jennie escape her quarters and kill herself, they would have made sure an

investigation resulted in such a finding. Moreover, the family would have wanted such a finding to be

announced. Whatever the particulars, Jennie was dead at only age thirty-one. Her body was brought from Madison

to Martintown for burial in the family graveyard.

During the interval from 1880 to 1882 while Jennie was confined, perhaps because he had an all-too-close look

at the standard of medical care at Mendota, Jacob decided he would become a doctor. He appears to have made an

effort to stay near Madison in order to check on Jennie, but he obtained his degree elsewhere. He attended

Hahnemann Medical College in Chicago. Hahnemann was a progressive school with a good reputation and the

credential would serve Jacob well in future. Incredible as it may seem to those of us today, the course of

study was a mere twenty weeks. As near as can be determined, the timing of Jacob’s attendance was in

early-to-mid-1881.

At some point during this period in Madison, Jacob (shown below right) became acquainted with Josephine

Florence Nye, daughter of

Sewell Nye, Jr. and Eliza Margaret Cathcart. She had been born about 1854 in Millville Township, Grant County,

WI, and raised on a farm near Madision in Fitchburg Township, Dane County, WI. Both of her parents were deceased

by 1880 and the Fitchburg Township family farm was in the hands of Josephine’s stepmother, who still had young

Sewell Nye, III to raise. Josephine was therefore in need of a means of carving out a destiny for herself. She

grew interested in the medical field. One question is whether Jacob set her on this course, or whether she

embarked upon this course and met Jacob as a consequence. Regardless of the answer, she attended Hahnemann in the

winter term of 1881/82, graduating 23 February 1882. A newspaper article published the next day reveals that she

was one of only eighteen female graduates out of a class of 263. Eighteen female graduates was a remarkable

number for that era. The article also reveals that Jacob was Josephine’s companion at the graduation banquet held

at the Grand Pacific Hotel. The date of the event was five days before Jennie’s death. From our perspective,

Jacob’s connection to Josephine in this manner -- even assuming their relationship at that time was entirely

platonic and collegial -- would qualify as an “awkward fact.”

Jacob apparently did not open a practice immediately upon obtaining his degree. His life circumstances probably

made that step seem precipitous. At first, he had Jennie to think of, and then after her death, he must have

concentrated upon finding a situation that would be suitable not only for himself, but for his children. So he

bided his time in Lancaster, Grant County, WI close to -- or even with -- his kinfolk. Meanwhile Josephine

opened a practice of her own. It was probably important to her to have that feather in her cap. She did not

keep the doors open long. Instead she became Jacob’s wife 14 September 1882, exchanging vows with him

in Fitchburg Township in front of her family members and long-time friends.

The newlyweds did not linger long in Wisconsin. Soon they -- along with

young Nathaniel, Agnes, and Arthur Hodge -- moved to Oskaloosa, Mahaska County, IA. They probably moved in 1883,

which is cited in a Hahnemann alumni publication as the year that Jacob began practicing medicine. The household

appears in Oskaloosa in the 1885 Iowa state census. An 1884/1885

business directory shows that Jacob was the junior partner at the medical office of Coffin & Hodge. (His

partner, who might have been better able to attract patients if he had changed his name to something

less ominous, was James L. Coffin.) The sojourn in Iowa was also also fated to be brief. By this point in

American history great numbers of people from the Midwest were heeding the siren call of California,

where the continuing expansion of the Southern Pacific Railroad network was opening up new, desirable

sections of the state for development. In June, 1887, the Hodges set out for Los Angeles County, and soon

made a home in Pasadena. The Coffin clan came along as well and remained close neighbors of the Hodges for

many years, though the medical partnership did not endure -- James had come to the alliance as an elderly

man on the verge of retirement.

The newlyweds did not linger long in Wisconsin. Soon they -- along with

young Nathaniel, Agnes, and Arthur Hodge -- moved to Oskaloosa, Mahaska County, IA. They probably moved in 1883,

which is cited in a Hahnemann alumni publication as the year that Jacob began practicing medicine. The household

appears in Oskaloosa in the 1885 Iowa state census. An 1884/1885

business directory shows that Jacob was the junior partner at the medical office of Coffin & Hodge. (His

partner, who might have been better able to attract patients if he had changed his name to something

less ominous, was James L. Coffin.) The sojourn in Iowa was also also fated to be brief. By this point in

American history great numbers of people from the Midwest were heeding the siren call of California,

where the continuing expansion of the Southern Pacific Railroad network was opening up new, desirable

sections of the state for development. In June, 1887, the Hodges set out for Los Angeles County, and soon

made a home in Pasadena. The Coffin clan came along as well and remained close neighbors of the Hodges for

many years, though the medical partnership did not endure -- James had come to the alliance as an elderly

man on the verge of retirement.

Jacob would become a prominent man in Pasadena, not only as a physician but as a pioneer and community leader.

In the early days, it is likely that Josephine assisted him in the medical side of his professional endeavors.

However, in keeping with the status of women in the Victorian Era any on-the-job contribution she made went

unheralded. No documentation has survived to indicate she was more than a wife and homemaker. That said, she

would seem to have been the sort to do more than that. It fits her profile. She had graduated from a top

institution. She had delayed marriage until age twenty-eight. She then had no offspring. She certainly had

the training, intelligence, and means to have done quite a bit, even if she had to do so behind the scenes.

Perhaps if she had survived longer, the question could be answered, but she passed away 1 October 1892, only

five years after the family had come to its new home.

Pasadena was a tiny hamlet in 1887. Coyotes ran through its dirt streets and the area, first settled only a

decade earlier, was still in a primitive early phase of its existence. It was growing so fast immigrants often

had to live in tents while new housing was built to accommodate them. The Hodges moved into a fine large

house at 851 North Raymond Avenue. Judging by the photo below, the building doubled as Jacob’s medical

office. However, an 1888 business directory confirms he had a separate office at 26 S. Fair Oaks Avenue.

The family thrived in their new environment. For the next several decades, the Hodges were a fixture of

Pasadena society. In addition to the family home, Jacob acquired other real estate. One of the most

noteworthy examples was a forty-five acre tract consisting of the upper portion of a hill in Linda Vista,

purchased in 1888, which soon began to be referred to as Hodge’s Peak. Jacob built a twelve-foot-wide wagon

road to the summit and erected a windmill there. He seems to have done so in order to power the pump that

brought up water that he and his sons would bottle and sell as a health remedy called Liviti. (Hahnemann

College was a homeopathic institute, and Jacob had become versed not only in traditional medical techniques

such as surgery and bone-setting, but understood how to market “patent medicine” as well.) The Hodges sold

their Liviti water only a few years, but it was so successful they found a ready buyer for the business.

Jacob is repeatedly mentioned in documents on the early history of Pasadena. Some references to him are

mundane, such as business directory entries and a mention that he was the first financial secretary of

the fraternal lodge, the Independent Order of Foresters -- Court of Drown of the Valley No. 817. On the

more colorful side, he was on hand at the fringes of a great fire in 1889, treating its victims (not all

of whom could be saved). In 1891 he was on the board of incorporation for Throop Polytechnic Institute,

which would a generation later evolve into the famous California Institute of Technology -- Cal Tech.

Son Arthur Judson Hodge would soon be among the early crops of students of Father Throop, the founder

and original headmaster.

The home of Jacob Hodge and family at 851 North Raymond Avenue, Pasadena, CA during the late

1880s or early 1890s. The sign out front reads “Dr. J.S. Hodge PHYSICIAN - SURGEON.”

In 1894 Jacob, now president of the Southern California Homeopathic Medicine Society, convinced city

officials to assist in the establishing of a hospital, a level of infrastructure previously unknown in

Pasadena. It was called Dr. Hodge’s Receiving Hospital and Surgical Institute, the name being an accurate

reflection of Jacob’s position as its director. The first incarnation of the facility

opened in January, 1895 as Jacob leased rooms ten through fourteen of the local Masonic Temple at the

intersection of Raymond and Colorado. The first patient there was a man named Ted Dobbins, who was suffering

from a broken leg. In August and September, two floors of brand-new, state-of-the-art, pre-planned treatment

suites and patient wards were built into the second and third floor of the Torrance and McGilvray block, at

the northwest corner of the intersection of Green Street and Raymond Avenue, above the Staats real estate

offices. The first patients here were a Miss Lyda Nichol and a Mrs. Putnam. This was a true hospital, with

other physicians besides Jacob caring for its patients, and a full staff of nurses -- the place also served

as a school for nurses. Jacob remained the director for only a few years. He found the administrative duties

interfered too much with his ability to tend to his private medical practice. He sold his interest to Ella

Joraschky, the facility’s original matron of nurses, and her husband August Joraschky. The Joraschkys changed

the name to Pasadena Hospital. However, August apparently was not a physician. Local citizens did not

have the same sort of confidence in him they had had in Jacob. Potential customers went elsewhere for

treatment to such a degree that the Joraschkys went out of business in October, 1899. Soon the city founded

a new hospital at a new site. The name Pasadena Hospital was retained, along with some of the equipment (and

perhaps some of the staff) from the Torrance and McGilvray locale. Much later it became Huntington Memorial

Hospital.

Pasadena attained such a reputation as a healthy environment, both for the quality of its resident medical

personnel and its mild climate and the clarity of its air that large numbers of people sought out the city

to try to recover when suffering from a chronic condition. Among those individuals was Chicago lumberman

Charles Eldred, who came west in approximately 1891 with his wife, the former Cora Wilkins, and their teenaged

children Cora and Elisha. Somehow or another, whether it was because Jacob was Charles’s doctor or simply

because the families liked each other, the Eldreds began boarding at 851 N. Raymond, establishing

themselves there in late 1892 or early 1893 not long after Josephine had passed away. The arrangement

continued for two years, and it was at the Hodge home that Charles died 13 March 1895.

Upon being widowed, Cora eventually moved out, but how soon she did so is not apparent. Certainly she and

her kids remained based in Pasadena for a while. She may not have departed Jacob’s home until she departed

Pasadena entirely, which seems to have been in 1896 or early 1897 when her mother, a Pasadena resident at

the time Charles died, returned to Chicago. Cora may have gone with her. However, Jacob had grown to like

her company, and assuming she left at all, he lured her back with a proposal of marriage. The

pair were wed 7 July 1897 in Chicago. She reoccupied 851 N. Raymond with

a new status -- very much able to make the handsome residence her own inasmuch as Jacob’s kids had spread

their wings, or were in the process of doing so.

Given that Jacob had bowed out of hospital administration, he had greater freedom to devote attention to

his new new spouse, and perhaps part of his decision to scale back was to be able attend to the domestic

side of his existence. Unfortunately, Jacob and Cora did not end up having a lot of time together. In the

late summer of 1900, Jacob was stricken

by what his obituary variously describes as leukemia and lymphatic anemia. He succumbed 22 October 1900.

His cremains were interred at Mountain View Cemetery, Altadena, Los Angeles County, CA. Many other

Hodges would come to rest beside him at Mountain View Cemetery.

Cora Wilkins Eldred Hodge (born 4 August 1852 in Detroit, MI to David Wilkins and Myrtylla Parr) outlived

Jacob by many years. Having lost one husband when he was only forty-eight years old and her second when

he was only fifty-two, she did not give Fate the chance to do it to her again. She remained single for the

rest of her life. She finally died 29 June 1933 in San Diego, CA. Her Eldred children continued to reside in

southern California lifelong, both passing away in the 1950s.

Children of Jennie Edith Martin

with Jacob Sylvester Hodge

Nathaniel

M. Hodge

Agnes Leona

Hodge

Adrian

Hodge

Arthur Judson

Hodge

For genealogical details, click on

each of the names.

To return to the Martin/Strader Family main page, click here.

Jennie Edith Martin,

fourth of the fourteen children of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, was born 1 November 1850 in

Martintown, Green County, WI, meaning that she was the first of Nathaniel and Hannah’s offspring to be

born after the family had become established in its longterm home.

Jennie Edith Martin,

fourth of the fourteen children of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, was born 1 November 1850 in

Martintown, Green County, WI, meaning that she was the first of Nathaniel and Hannah’s offspring to be

born after the family had become established in its longterm home. The couple began their married lives as a farm family upon a

large parcel of land along the Pecatonica

River on the mill side just over the state line -- acreage which Jennie received as a dowry gift from

her parents. Technically, this meant they had an address of Winslow, Stephenson County, IL, though they

were more accurately residents of rural Martintown. In the summer of 1869 Jennie and Jacob became the

parents of Nathaniel M. Hodge, the very first grandchild of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, and the

first of several descendants to bear the patriarch’s given name. With a growing family, Jacob was eager

to bring in extra income, so he formed a partnership with Jennie’s brother Horatio Woodman Martin. The

two young men operated Martintown’s general store, which had been opened by J.W. Mitchell in 1869 and then

had been run by William Hodges, the original postmaster of the village. (William was not a relative of

Jacob -- one was a Hodges, the other a Hodge.)

The couple began their married lives as a farm family upon a

large parcel of land along the Pecatonica

River on the mill side just over the state line -- acreage which Jennie received as a dowry gift from

her parents. Technically, this meant they had an address of Winslow, Stephenson County, IL, though they

were more accurately residents of rural Martintown. In the summer of 1869 Jennie and Jacob became the

parents of Nathaniel M. Hodge, the very first grandchild of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, and the

first of several descendants to bear the patriarch’s given name. With a growing family, Jacob was eager

to bring in extra income, so he formed a partnership with Jennie’s brother Horatio Woodman Martin. The

two young men operated Martintown’s general store, which had been opened by J.W. Mitchell in 1869 and then

had been run by William Hodges, the original postmaster of the village. (William was not a relative of

Jacob -- one was a Hodges, the other a Hodge.) Jennie apparently never left Mendota. She may have committed

suicide. Family lore says she drowned in Lake Mendota. However, the date of death was 28 February 1882. She

would not have been in the water for any legitimate reason such as a swimming party for the patients. At

that time of year in Wisconsin, no one goes swimming -- water temperatures are at best just above freezing.

If she went into the lake at all, it was by sneaking out of the hospital and using the water to help ensure

her death. An article in the 15 March 1882 edition of The Weekly Wisconsin of Milwaukee mentions an

investigation to put to rest “startling rumors” about her death, and that the result of said investigation

was that she had died of brain fever. This is unfortunately not definitive. If the asylum wanted to cover up

its own incompetence in letting Jennie escape her quarters and kill herself, they would have made sure an

investigation resulted in such a finding. Moreover, the family would have wanted such a finding to be

announced. Whatever the particulars, Jennie was dead at only age thirty-one. Her body was brought from Madison

to Martintown for burial in the family graveyard.

Jennie apparently never left Mendota. She may have committed

suicide. Family lore says she drowned in Lake Mendota. However, the date of death was 28 February 1882. She

would not have been in the water for any legitimate reason such as a swimming party for the patients. At

that time of year in Wisconsin, no one goes swimming -- water temperatures are at best just above freezing.

If she went into the lake at all, it was by sneaking out of the hospital and using the water to help ensure

her death. An article in the 15 March 1882 edition of The Weekly Wisconsin of Milwaukee mentions an

investigation to put to rest “startling rumors” about her death, and that the result of said investigation

was that she had died of brain fever. This is unfortunately not definitive. If the asylum wanted to cover up

its own incompetence in letting Jennie escape her quarters and kill herself, they would have made sure an

investigation resulted in such a finding. Moreover, the family would have wanted such a finding to be

announced. Whatever the particulars, Jennie was dead at only age thirty-one. Her body was brought from Madison

to Martintown for burial in the family graveyard. The newlyweds did not linger long in Wisconsin. Soon they -- along with

young Nathaniel, Agnes, and Arthur Hodge -- moved to Oskaloosa, Mahaska County, IA. They probably moved in 1883,

which is cited in a Hahnemann alumni publication as the year that Jacob began practicing medicine. The household

appears in Oskaloosa in the 1885 Iowa state census. An 1884/1885

business directory shows that Jacob was the junior partner at the medical office of Coffin & Hodge. (His

partner, who might have been better able to attract patients if he had changed his name to something

less ominous, was James L. Coffin.) The sojourn in Iowa was also also fated to be brief. By this point in

American history great numbers of people from the Midwest were heeding the siren call of California,

where the continuing expansion of the Southern Pacific Railroad network was opening up new, desirable

sections of the state for development. In June, 1887, the Hodges set out for Los Angeles County, and soon

made a home in Pasadena. The Coffin clan came along as well and remained close neighbors of the Hodges for

many years, though the medical partnership did not endure -- James had come to the alliance as an elderly

man on the verge of retirement.

The newlyweds did not linger long in Wisconsin. Soon they -- along with

young Nathaniel, Agnes, and Arthur Hodge -- moved to Oskaloosa, Mahaska County, IA. They probably moved in 1883,

which is cited in a Hahnemann alumni publication as the year that Jacob began practicing medicine. The household

appears in Oskaloosa in the 1885 Iowa state census. An 1884/1885

business directory shows that Jacob was the junior partner at the medical office of Coffin & Hodge. (His

partner, who might have been better able to attract patients if he had changed his name to something

less ominous, was James L. Coffin.) The sojourn in Iowa was also also fated to be brief. By this point in

American history great numbers of people from the Midwest were heeding the siren call of California,

where the continuing expansion of the Southern Pacific Railroad network was opening up new, desirable

sections of the state for development. In June, 1887, the Hodges set out for Los Angeles County, and soon

made a home in Pasadena. The Coffin clan came along as well and remained close neighbors of the Hodges for

many years, though the medical partnership did not endure -- James had come to the alliance as an elderly

man on the verge of retirement.