Maria Rautiainen

Maria Rautiainen was born 15 February 1893 in Tyrnävä in northwestern

Finland. She was the seventh, eighth, or more likely the ninth-born child of the twelve children of Josef

(nicknamed Juuso) Rautiainen (20 December 1859 - 23 June 1932) and his first wife Marja (aka Maria)

Henriikka Perttunen (5 April 1863 - 9 August 1900). Her name looks like it should be pronounced the way

it is in Spanish, but in Finnish, the emphasis is put on the first syllable, hence it was “MAHR ee ah.”

After coming to America, she shifted to using Mary and Marie. Most of her descendants knew her as Mary, but

she tended to use Marie in documents and when signing her signature and when addressed by her peers.

In the early 1960s the first of her great-grandchildren took to calling her Mumu, a Finnish nickname

for great-grandma, and this was how the younger generations of the clan increasingly knew her during

the final forty years of her life. She would happily answer to any of these names.

Maria Rautiainen was born 15 February 1893 in Tyrnävä in northwestern

Finland. She was the seventh, eighth, or more likely the ninth-born child of the twelve children of Josef

(nicknamed Juuso) Rautiainen (20 December 1859 - 23 June 1932) and his first wife Marja (aka Maria)

Henriikka Perttunen (5 April 1863 - 9 August 1900). Her name looks like it should be pronounced the way

it is in Spanish, but in Finnish, the emphasis is put on the first syllable, hence it was “MAHR ee ah.”

After coming to America, she shifted to using Mary and Marie. Most of her descendants knew her as Mary, but

she tended to use Marie in documents and when signing her signature and when addressed by her peers.

In the early 1960s the first of her great-grandchildren took to calling her Mumu, a Finnish nickname

for great-grandma, and this was how the younger generations of the clan increasingly knew her during

the final forty years of her life. She would happily answer to any of these names.

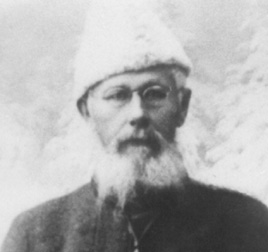

Juuso Rautianen was a sheriff and a prosecutor for a large district of Oulu -- Oulu being the province

of Finland situated immediately south of Lapland. Juuso’s jurisdiction extended over a large area in

geographical terms, and at times the entire household packed up and moved into new lodgings in order

to reside near his workplaces. He and Marja had started out their life together in the city of Oulu.

They had come to Tyrnävä not long before Maria’s birth. When Maria was about two years old, the family

settled in Vihanti, a small town located south of Oulu. Juuso acquired land there. The farm would later

be lost to foreclosure, but from that mid-1890s point onward, Vihanti would come to be thought of as

the family’s true home. As an adult, Maria certainly thought of herself as “being from Vihanti.” This

was true despite relocations, the biggest disruption being a two-year sojourn in the port town of

Raahe.

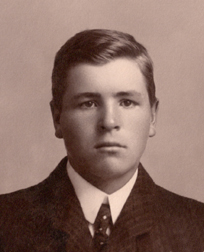

Juuso (shown at right) regarded education for females as a frill. Many families felt the same,

in part because class terms had to be paid for. Juuso felt that there was barely enough money to take

care of the boys, and he was not unjustified in coming to that conclusion. In any event, he permitted

Maria to attend only one month of classes at a circuit school, where she learned reading and basic

mathematics. Maria and her sisters were however taught within the home. Also, given that the Rautiainens

were members of the Finnish Lutheran Church, Maria received additional instruction in reading and

writing of Scripture at the family parish in order to be able to be confirmed. Maria had the wit and

talent to use her limited opportunities, and succeeded in becoming literate.

In 1900, Marja Henriikka Perttunen Rautianen passed away abruptly at age thirty-seven due to hemorrhaging

caused by a late miscarriage. The baby was the twelfth of those tallied above. Three other children of

the family had also died in infancy or at birth, an all-too-common phenomenon in the uncompromising

climate of northernmost Europe. Maria in fact was the second child of the household to be named Maria.

Re-using favorite names when offspring died young was a frequently-seen custom in old-time Finland.

Maria wrote a “letter to all” about her life while in her

mid-nineties. She had been reluctant to write a memoir because her skill at written English was not what

she would have liked, but in 1986 her granddaughter Carol Smeds Krehbiel convinced her to do so by

pointing out that she could write the document in Finnish, and her Finnish granddaughter-in-law Paula

Hakulinen Smeds could translate it. The account has this to say about her childhood: I don’t have many

memories of my mother, just a few of some special occasions. Like once Mother needed to go to Oulu and she

took me along. When we got to the market square, we stopped by a man selling shoes and he offered a pair

for me to try on. Once I had the shoes on, I would not take them off again and Mother ended up paying for

them. However, after we had done some more walking the soles fell off. I don’t remember what we did with

them then. On another occasion Mother was making a dress for Sofia. I don’t remember for what reason she

tried it on me, but of course I did not want to take it off. I was screaming and fighting and remember

hearing Mother say what a bad girl I was to scratch her like that. Father happened to be within hearing

distance, found a twig or two and used them on my bottom. That was the last time I got a whipping.

Maria wrote a “letter to all” about her life while in her

mid-nineties. She had been reluctant to write a memoir because her skill at written English was not what

she would have liked, but in 1986 her granddaughter Carol Smeds Krehbiel convinced her to do so by

pointing out that she could write the document in Finnish, and her Finnish granddaughter-in-law Paula

Hakulinen Smeds could translate it. The account has this to say about her childhood: I don’t have many

memories of my mother, just a few of some special occasions. Like once Mother needed to go to Oulu and she

took me along. When we got to the market square, we stopped by a man selling shoes and he offered a pair

for me to try on. Once I had the shoes on, I would not take them off again and Mother ended up paying for

them. However, after we had done some more walking the soles fell off. I don’t remember what we did with

them then. On another occasion Mother was making a dress for Sofia. I don’t remember for what reason she

tried it on me, but of course I did not want to take it off. I was screaming and fighting and remember

hearing Mother say what a bad girl I was to scratch her like that. Father happened to be within hearing

distance, found a twig or two and used them on my bottom. That was the last time I got a whipping.

Of the end of the two-year sojourn in Raahe, Maria commented: The return to Vihanti happened

at the time of a general strike. For a week the trains would not run, so Father had to find three

horses to get us home. At that time horse rides were called “vossikka.”

I do remember Mother’s funeral. Her coffin was outside in the yard with the lid open, her hair

flowing in the breeze. I heard someone say she was the best of women.

A year after becoming a widower, Juuso married Ida Hyvarinen from Petajaskoski. She was fifteen years

younger than he, so the couple would continue to have children as late as 1920. They had seven altogether.

The first four were born while Maria still resided in Finland, and she assisted her step-mother in

caring for these young ones. In later decades, despite a separation of thousands of miles, Maria

remained particularly close to half-sister Impi. She also maintained contact with the youngest three

of the brood, even though she did not meet them face-to-face until her first trip back to her mother

country, which did not occur until 1959. In the 1960s and 1970s, half-siblings Urho and Liisa would

visit California multiple times, enchanted by the big sister they had known only through letters and

phone calls until they were all middle-aged or older.

“Big” sister is a relative term. Maria remained short even in adulthood -- and short even by the

standards of her family. She perhaps topped out at five feet in in her twenties and thirties, but as she

aged she shrank to no more than four eleven. She was plump and buxom, partly due to genetics and

partly because she never lost her affection for butter, sugar, milk, and flour. However, she was by

no means plump in a lazy way. She lived robustly, displaying an astonishing degree of energy and

stamina, a living testament that calories really are the means for the human body to get what it

needs to thrive.

Maria came of age at a time when large numbers of Finns were leaving for the United States. Not only

was America the “land of opportunity” in the classic sense, but emigrating also solved a dilemma faced

by young Finnish males. If they remained past age eighteen, they could be conscripted to serve in the Russian

Army. (The Tsarist monarchy had controlled Finland for generations, and considered the country a province

of Russia.) Often these young soldiers would be stationed all the way across the continent in eastern

Siberia, and if they perished in the harsh conditions there -- including perhaps being killed in combat

in the Russo-Japanese War -- their families sometimes never even heard what became of them. More

than one Finnish young man therefore fled the country at age seventeen. Where the males went, the

females naturally followed. The first among the Rautianen family to go was eldest sister Anna. A neighbor

woman from Vihanti had moved to San Francisco, but had left most of her wealth in the form of property

and possessions in Finland out of fear that any funds she carried might be stolen in transit or

swindled from her at her destination. Once she was safely settled in her new home, she arranged that

Juuso Rautiainen sell her assets back home. The woman didn’t trust banks, so she requested

that Juuso find some sort of courier to bring the money. Juuso asked Anna if she wanted to move to

America. Anna, though still only in her teens, agreed to the adventure. She travelled alone, landing

at a Canadian port and coming by train across the continent. Anna knew no English and was so

afraid the train would leave without her during the brief meal stops that she did not get off and thus

arrived in San Francisco faint from hunger. But she made it. She found lodgings and employment with the

help of local Finns. The social activities of the Finnish Brotherhood in San Francisco and Berkeley

became her main social outlet, and through this means she met and was courted by Jakob Herman “Jack”

Smeds, a Finn who had come to California in 1901, having grown up just down the coast from the towns

where she had been raised. Soon Annie was pregnant and she and Jack decided to get married.

Annie was happy with her new life. Jack was

employed as a jeweller with Shreve and Company, a large firm, and so the household had a steady

income. In 1906, he became a citizen, giving them added status. The family grew. The one fly in the

ointment for Annie was that she lived so far away from all of her birth kin. In 1910, thanks to their

savings and Jack’s status as a citizen, the couple offered Maria sponsorship and the fare to come to

America. Maria, still only seventeen, was excited by the idea, even though Anna was by then something

of a stranger in that she had not seen her sister for seven years. Arrangements were made and Maria

was on her way, journeying across the Atlantic on a Cunard liner. From her port of entry (unknown at

this time) she boarded a train for the overland portion of the journey. The trek as a whole took

three to four weeks. She arrived in San Francisco in September, 1910.

Annie was happy with her new life. Jack was

employed as a jeweller with Shreve and Company, a large firm, and so the household had a steady

income. In 1906, he became a citizen, giving them added status. The family grew. The one fly in the

ointment for Annie was that she lived so far away from all of her birth kin. In 1910, thanks to their

savings and Jack’s status as a citizen, the couple offered Maria sponsorship and the fare to come to

America. Maria, still only seventeen, was excited by the idea, even though Anna was by then something

of a stranger in that she had not seen her sister for seven years. Arrangements were made and Maria

was on her way, journeying across the Atlantic on a Cunard liner. From her port of entry (unknown at

this time) she boarded a train for the overland portion of the journey. The trek as a whole took

three to four weeks. She arrived in San Francisco in September, 1910.

It was a tremendous experience for me. Jack and Anna and their two daughters, Sylvia and Lillian,

came to meet me [at the depot]. I was extremely tired. I stood a little behind the

other passengers when Jack came and asked if I was Maria Rautiainen. I said yes and soon Anna and

the girls came over, too. I don’t know why I expected Anna to embrace me, but she put out her

hand instead. At that time we Finns did not want to show our affection.

We got into a streetcar and I remember wondering if the travelling would ever come to an end. At

that time Anna and Jack lived in the Temperance Society Hall as caretakers. I still remember the

telephone number over there: Mission 6065. I stayed with them for a few weeks till they found me a

place of employment.

(Shown at left is the very place where Mary spent the first few weeks of her life as a resident

of the United States. This was how the caretakers’ annex of the temperance hall looked on the morning

of 7 June 2013 when visited by her grandson Dave Smeds. The hall and the annex are still standing at

425 Hoffman Street in the Noe Valley/Upper Market neighborhood of San Francisco more than one hundred

years after she -- and Jack and Annie -- were based there.)

Maria remained in San Francisco a total of about sixteen months, moving three times during that

span. With no formal skills, her jobs consisted of childcare and housework as a live-in maid for

room and board and approximately ten dollars a month in wages. (A breadwinner of that era could

expect to earn five to eight times that amount.) During this time she became fluent in English; the

first housewife she worked for was very helpful in that regard, and of course all of the children

she cared for were quick to correct her linguistic mistakes. It was also in that first home that she

gave up being known as Maria, because a Maria was already living there.

Life in San Francisco was exciting compared to the bleakness of northern Finland, and Mary

enjoyed her independence and opportunities. She was bold enough in her enjoyment that Annie and

Jack worried she was being a little too spirited, if not frivolous. (The image at right

captures Mary on one of her adventures. She is the young lady in the center. The other two are

friends she had made among the other housemaids in San Francisco. The trio are shown here while

on an excursion they took to Boyes Hot Springs, a small resort community located thirty-five miles

due north of San Francisco. The locale is in the heart of Sonoma County’s “Valley of the Moon,”

hence the “sitting in the moon” pose. The photographer printed the image onto a post card on the

spot, which Mary mailed to Annie 9 January 1912. Mary was not quite nineteen years old.)

Annie and Jack decided a marriage would be

just the thing to get Mary on the right track and steer her toward the maturity she needed. But

there was a further problem in that so few men of their acquaintance seemed suitable. As Mary put

it in her memoir, I got to know many young Finnish men who stopped by the Temperance Hall and

according to Anna none were any good, except maybe one and he was in poor health. The fact was

that many of the bachelors Annie and Jack knew were alcoholics who, in spite of their participation

in Temperance Hall meetings, were still struggling with their addiction. But then a solution

presented itself. At my first Christmas there, Jack’s brother William came to stay over

the holidays. Anna thought he was one of the best, if not the best. I wasn’t too

interested since he did not even dance and at the time dancing was my favorite entertainment.

Afterward Anna would take every possible opportunity to wonder why I didn’t like Billy.

Annie and Jack decided a marriage would be

just the thing to get Mary on the right track and steer her toward the maturity she needed. But

there was a further problem in that so few men of their acquaintance seemed suitable. As Mary put

it in her memoir, I got to know many young Finnish men who stopped by the Temperance Hall and

according to Anna none were any good, except maybe one and he was in poor health. The fact was

that many of the bachelors Annie and Jack knew were alcoholics who, in spite of their participation

in Temperance Hall meetings, were still struggling with their addiction. But then a solution

presented itself. At my first Christmas there, Jack’s brother William came to stay over

the holidays. Anna thought he was one of the best, if not the best. I wasn’t too

interested since he did not even dance and at the time dancing was my favorite entertainment.

Afterward Anna would take every possible opportunity to wonder why I didn’t like Billy.

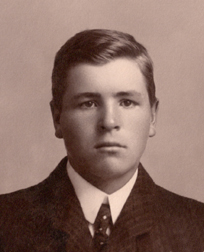

Billy (born Vilhelm) Smeds had come to

California in 1904 and gone to work in the lumber industry in the redwoods near Eureka, CA. Not long

after that Jack, along with three immigrant colleagues, had purchased land near Reedley, Fresno

County, CA. Jack had found it a challenge to administer his farm from San Francisco, where he stayed

in order to earn the money to pay the mortgage. Therefore at the end of 1907 he had arranged with Billy

and their father Herman to move to Reedley to take care of and improve the property. Billy was reserved

and he often behaved as though a cloud of gloom hung over his head -- in contrast to his

twinkle-in-the-eye older brother -- so it was not surprising he would not impress a vivacious

eighteen-year-old. However, he was solid and hard-working and a man of integrity. He was indeed “one

of the best, if not the best” prospects to make a good husband. Mary’s rejection of him proved to be

temporary.

In 1911, Billy came again to San Francisco for Christmas and stayed a couple of weeks. I went with him

to the movies and here and there. I had by then become tired of my job, and so we agreed to get married.

Both Anna and Jack were very pleased to hear that. We were married on 24 January 1912. At that time Anna

and Jack lived in Glen Park; I don’t remember at which number. (It was 2 Mizpah Street.) Anyway,

their place was small, so there were not many wedding guests -- a couple of girlfriends of mine and some

friends of Anna and Jack. Pastor Lauri Ahlman married us. (The girlfriends may well have been the

same pair shown in the Valley of the Moon post card. That excursion occurred just two weeks before the

wedding and may have represented Mary’s last frolic as a single woman.)

A day or two after the wedding we travelled to Reedley. Billy’s father met us at the station. I

don’t remember what his greeting to me was, but to Billy he said that I was very small. It was a most

beautiful afternoon when we rode along Reed Avenue.

Mary and Billy did not share a native language. Hers was Finnish. His was Swedish. Mary refused to learn

Swedish. Billy however had become versed in Finnish, in part because the majority of the Finns in

Reedley were speakers of Finnish and he wanted to be able to keep up with their conversations when he

was among them. He went to the effort of learning more, at least enough that the couple could

communicate what needed to be communicated. Of course, the use of English was an alternative. Neither

had become proficient by 1912, but their command of it improved over the course of the rest of the

decade. And then once their kids began going to school and began treating English as their language of

first resort, Mary and Billy followed suit. Herman Smeds on the other hand stuck entirely to Swedish,

apparently feeling that at nearly sixty years of age, it was too much bother to do otherwise. Mary felt

left out when the two men conversed -- particularly since Billy was not the sort of fellow to say much

even under the best of circumstances.

The house she came to was somewhat small. Four rooms, only

two of which were furnished. There was no electricity and no plumbing. For light, there were oil lamps.

For water, there were buckets. For certain other basic needs, there were chamberpots and the outhouse.

Mary was accustomed to a provincial lifestyle, but she had lived in a big city for over a year and had

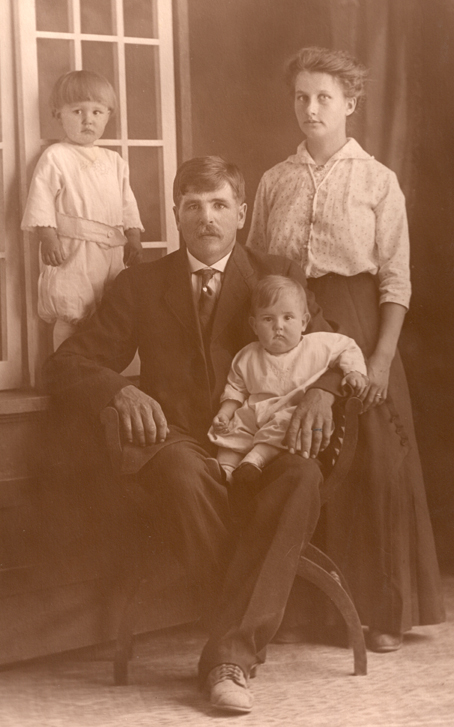

expectations as a bride. She told Billy (shown at left) he had to make it possible for

her to get water for cooking without having to fetch it from the well, or she wouldn’t even step

through the door. He saw that she was serious, and spent some of their first day in Reedley setting

up a barrel atop a platform of posts. He filled the barrel with water and ran a hose from the bottom

of it into the house. Gravity then allowed Mary to hand-pump water into the kitchen sink when she

needed it. Having made her point, she laid claim to the home she would live in until Jack and

Annie moved to Reedley.

The house she came to was somewhat small. Four rooms, only

two of which were furnished. There was no electricity and no plumbing. For light, there were oil lamps.

For water, there were buckets. For certain other basic needs, there were chamberpots and the outhouse.

Mary was accustomed to a provincial lifestyle, but she had lived in a big city for over a year and had

expectations as a bride. She told Billy (shown at left) he had to make it possible for

her to get water for cooking without having to fetch it from the well, or she wouldn’t even step

through the door. He saw that she was serious, and spent some of their first day in Reedley setting

up a barrel atop a platform of posts. He filled the barrel with water and ran a hose from the bottom

of it into the house. Gravity then allowed Mary to hand-pump water into the kitchen sink when she

needed it. Having made her point, she laid claim to the home she would live in until Jack and

Annie moved to Reedley.

The early years on the farm were an ordeal in terms of labor for both husband and wife. Firewood

was created with axe, maul, and wedge. Tilling was done when possible with a borrowed team of

plowhorses, but even that was a luxury; most of the time Billy created furrows by hand with his

shovel and/or hoe. Keeping the irrigation pump primed sometimes meant sleeping down the hill beside

the noisy contraption because if it stopped during the night, the weight of the flywheel made it

impossible to get going again without the aid of at least one other man. As for Mary, she had to do

the laundry and make the butter and sew the clothes by hand. To cook she had a woodstove. In the

brutal heat of summer days she resorted to a second woodstove Billy had set up outside

beneath a makeshift arbor. Even the ninety to one-hundred five degree temperatures out there were

better than remaining trapped in a kitchen that had itself become an oven.

Fresh milk was obtained by squeezing it from the family cows. The livestock was kept down at the

river, a good two hundred paces away. Herman Smeds would sit in his rocking chair and cackle out

loud to watch Mary head down each morning escorted -- much to her annoyance -- by every other

animal the family possessed, consisting of a wedding-gift pig, two dogs, and a cat.

The pig did not last long. It was, of course, scheduled to be butchered when it finished growing,

but it hastened its own demise by shadowing Mary so relentlessly. She complained about the behavior

until Billy put a collar on the beast and tethered it in the yard, depriving it even of the chance to

wait for its beloved human in its favorite spot right outside the door. The next morning they

discovered that the creature had been so desperate to get free that it had tangled a front leg inside

the collar and in so doing, strangled itself. The body had cooled down and the blood had congealed,

ruining the meat for consumption.

A year into the marriage, as Mary was turning twenty, the couple’s first child was conceived. No

midwife was available locally and doctors came and went in a circuit, so Mary spent the end of the

pregnancy with Annie and Jack in San Francisco, where she gave birth to a son on the first of

September, 1913. He was named Roy William Smeds in honor of the baby that Jack and Annie had lost

in 1909. Happily, this second Roy William Smeds thrived.

Only a few months after little Roy was brought home to the farm, Herman Smeds began having tenderness

in the throat that proved to be an aggressive case of cancer. Knowing he would not survive the

illness, he chose to end his pain by hanging himself from one of the huge oak trees by the river in

early February, 1914. By then, Mary was already nearly two months pregnant with a second child. She

had been told brand-new nursing mothers were not usually fertile. However, in her case, there was

no such respite. Second son Joseph Alfred Smeds therefore arrived barely more than a year

after the appearance of his older brother. The name Joseph was in honor of Mary’s father Josef, but

so as not to saddle him with the label “Little Joseph,” he was known lifelong by his middle name.

Alfred’s birth did not require a trip to the Bay Area. By late 1914 a trusted doctor was available

in Reedley, and neighbor Katherine Tenhunen cared for Mary during the traditional post-partum

sequestering.

In 1915, Billy and Mary were able to accomplish a long-sought goal, and obtain acreage of their

own. The land was right across Holbrook Avenue, the country lane along which the four immigrants,

Jack included, had established their farms. The parcel was farther from the river, and not as

ideal, but that meant it was cheaper. Billy began building a house. At this point, Jack decided the

time was ripe to quit Shreve and Company and become a full-time farmer, in part because he had just

bought out Karl Nordell, one of the original group of four. Annie and Jack and their two pre-teen

girls arrived before Billy had finished building the house on the new parcel, and so for the time

being, both Smeds families crowded into the original farmhouse, as they sometimes did when Annie

and Jack came down to help with the raisin harvest. Then the men’s sister Amanda and her husband

Charles Strom arrived in Reedley as well. Amanda and Charlie, who had remained in Eureka when Billy

had come south, had finally had enough of the redwoods and he more than enough of his workdays in

the forest. They were ready to start a family, and wanted to do so as farmers. Charlie found

available acreage about two miles to the east and the couple were soon ensconced there, but until

then, things were quite cozy.

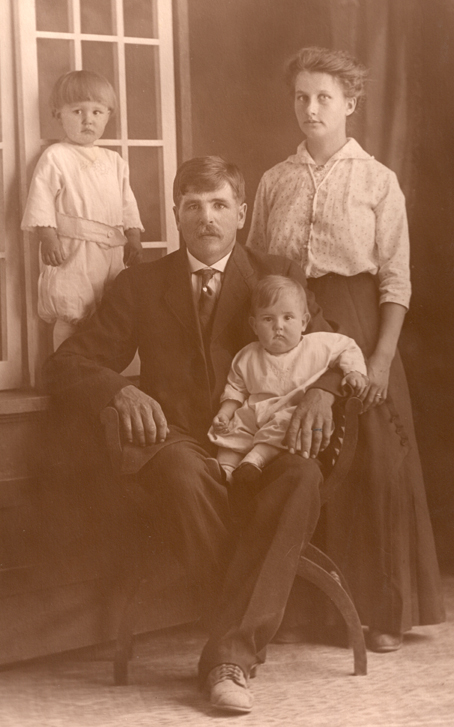

Here are members of the Smeds Family in front of the first of the family houses, the one that

sheltered so many of the clan in 1915. This photograph appears to have been taken about that

time. The woman in white is Mary. The woman with the wide-brimmed hat is Annie. Jack is standing with the

plow horses. The older girl is Sylvia; her sister Lillian is the one sitting with the dog. The

toddler is surely Roy -- wearing a dress as boy babies often did in that era. Roy’s apparent age

means that Alfred must have been a few months old, and was probably asleep in his crib indoors. The

man standing at the far left is a neighbor, possibly A.A. Westerlund. The building fell out of use

in the early decades of the farms and ceased to exist by the early 1960s.

The year after she and Billy became homeowners, Mary was struck by the only serious illness of her

extraordinarily long life. She came down with a case of typhoid fever. Knowing that her hair follicles

would probably be permanently ruined by the extended high temperature of her skin, she bought a wig and

tied her real hair into a tight braid and cut it off near the scalp. The stubble did indeed fall out

during the three weeks she occupied her sickbed. The hair that replaced it was thinner, wiry, its tone

flat and color no longer vibrant. But until she was an old woman with hair so white it seemed almost

blue, she was able to pull down a hat box from her closet and reveal a braid of thick, glossy, long,

straight, golden-highlighted auburn hair of the sort any young woman would be proud to possess.

The prolonged high fever may have cooked Mary’s ovaries and left her infertile. In any event, she

never experienced another pregnancy.

America entered World War I, and the economic turmoil of that two-year span made it extremely

difficult for farmers to stay afloat. Landowners began defaulting on their mortgages all up and

down the San Joaquin Valley. Billy was among those that could not make his payments. However, he

was willing to stay in place and keep faith with his chosen livelihood, and in the eye of the bank,

that made him better than many, including one of his neighbors, who had simply abandoned his

property and left for other employment prospects elsewhere. Billy was not only allowed to keep

his own acreage and pay when he could, but he obtained title to the piece closer to the river,

bordering on the north the acreage that he had managed for Jack and Annie for the better part of

a decade. The house right on Holbrook was destined to become a rental. Billy was eager to resume

living along the bluff, where he could look down on the beauty of the Kings River. He began

building yet another house. His first step was to set up a shack for a temporary sauna.

Only after he had enjoyed a few good sweats did he begin to erect the main structure. The home he

fashioned was modest in size but very well-built. It would serve the needs of a series of Smedses

and in-laws over the years, usually to young couples just beginning their lives together, such as

Alfred and his wife Josephine, and later a grandson of Jack and Annie, and later still a daughter

of that grandson, but not until after a two-year tenure by Alfred and Josephine’s eldest son and

his new wife. In the late 20th Century the parcel came into the possession of Roy’s daughter. In

Year 2000, as she and her husband retired and came back to their hometown to spend their twilight

years, they razed the house Billy had constructed -- which at over eighty years old was not

adequate for modern living -- and replaced it with a handsome, larger, up-to-date residence.

Through the 1920s the household routine was steady. The boys grew, attending Great Western Elementary

School and then Reedley High School. The large number of Finnish families in the Reedley area meant

that many friends were on hand for social occasions, including those of the local chapter of the

Finnish Brotherhood. Some of the latter organization’s events were held in association with the

Finnish Lutheran Church, but neither Mary nor Billy were especially religious. Family gatherings

were well attended, rotating between the homes of Mary and Billy, Annie and Jack, and Amanda and

Charlie. The latter couple had produced three girls between 1916 and 1920, and Annie and Jack had

become parents of their final child, Lawrence, in 1917, filling out the generation.

The two households of Smedses and the one of Stroms formed a unit whose bond lingers to this day.

Economically, things were usually on the edge. The Twenties may have been an era when the big

industrialists and stockholders did well, but small family farmers only scraped by. It was in these

years that Mary sometimes worked in local fruit-packing houses in order to bring some much-needed

cash. (The temptation is to use the cliché and say “extra” cash, but there was no “extra” aspect

to it. Whatever wages Mary could bring in were vitally needed.) She had worked outside the home in

her early years on the farm in the sense that everyone was callled upon during the harvest season

in an “all hands on deck” fashion to lay down bunches of grapes on the trays to get the crop made

into raisins before the first rainstorm of the autumn had a chance to appear. In general, though,

her responsibilities as a homemaker were a massive-enough undertaking. Now she made an exception

to that “usual role.” She was more proficient in English and therefore more employable. The family

finally had an automobile with which she could get to worksites. (The family’s first car had been

purchased in 1918. She and Billy could not have afforded to buy a replacement during the most

financially tenuous years of the 1920s, but their luck held. The vehicle was durable and served

them for eleven years.) And probably most important, Roy

and Alfred were old enough that they could be left at home without her. They could serve themselves

the food she had left for them, would wash the dishes, would get themselves bathed, etc. Sometimes

they were supervised by their neighbor Hilma North, though she was only a few years older than

they were. At other times, they stepped up. They did so again as adolescents. Billy’s

fieldwork demanded such long days and hard physical effort it could literally be back-breaking.

When Roy and Alfred were in their early teens, Billy was laid up for an entire season with back

trouble, and the youths had to do nearly all of his chores.

Somehow the mortgage was whittled down. Surprisingly, it was possible to add acreage -- if only

because so many neighbors were giving up. This became increasingly true at the beginning of the

Great Depression, resulting in the most significant of all Mary and Billy’s real-estate purchases.

The tenants who had been farming next door decided to move to Astoria, OR, where they could live

in a cooler, wetter, more northerly climate, among an even greater concentration of Finns. The

owners of the property were the Smeds family’s friends Fred and Katherine Tenhunen, who had left

Reedley in 1919. Fred’s jewelry store in Oakland, CA was doing very poor business as a result of

the economic downturn. The Tenhunens offered to sell the farm to Mary and Billy, who accepted. The

house was a prize. Fred

Tenhunen had built it in 1913 and had gone the extra mile in terms of its construction. He had been

mocked for being excessive when he installed wiring. The region had no electrical service, and none

was expected any time soon. Wiring in the walls was viewed as completely unnecessary. Yet within just

a year or two, the area north of Reedley was included in one of the early Rural Electrification

projects. The power grid reached the farm, and all of a sudden Fred Tenhunen was being congratulated

for his insight -- or at least his luck. Mary and Billy took possession of their new home by early

1930. This is where they would spend the rest of their lives together. Their address was 6469 S.

Holbrook Avenue.

In the 1930s, Roy and Alfred came of age. Roy spent a year at the University of California at

Berkeley. Alfred went to work for Standard Oil in Kern County, a hundred or so miles to the southwest.

Each soon found a wife, Alfred marrying Josephine Warner of Sanger (the next town northwest of

Reedley) in 1936, and Roy marrying Mildred Stone of Mountain Home, ID in 1937. Both boys soon

returned to the farm and began working for their father under the business partnership of William

Smeds and Sons,

with the intent of expanding the size and scope of the family holdings. When the country entered

World War II, the partnership took advantage of plummeting land prices and acquired a sixty-seven

acre parcel on Reed Avenue, just on the other side of the Laine farm from Jack and Annie’s main

acreage at the corner of Holbrook Avenue and Peter Avenue. One of the motives in acquiring this land

was that each farm permitted one male head of household of military-service age to be exempted from

the draft. Roy used the original farm’s exemption, and Alfred used the new one. The new farm would

be Alfred and Josephine’s home for over sixty years -- the rest of their lives.

Roy and Mildred built a large adobe house that shared a

yard with Mary and Billy. They raised two children. Alfred and Josephine had four kids. With two

grandkids only a few steps away and

the rest only a twenty-minute walk down a dirt lane, Mary was heavily involved in the lives of

this next generation, and knew each member well. She in turn was incredibly popular with them. She

doted on them, putting in regular babysitting shifts, teaching her granddaughters her recipes as

they grew older -- though no one attempted to keep up with her in the kitchen. She cooked the

old-fashioned, labor-intensive way, knowing her baking so instinctively

she never measured ingredients, but just grabbed handfuls of this or a dash of that whenever she

judged something was needed. She would bake pulla, the famous Swedish/Finnish sweet glazed braided

eggbread (much like Jewish challah, only spiced with cardamom) two or three times every week until she

was well over a hundred years of age. (Her recipe, as closely as it can be reproduced, can be found

on this website by clicking here.) When the grandchildren were

young she would make custards

even though it meant standing at a stove stirring for an hour straight. She would make

juustoleipaa, a homemade cheese often made with reindeer milk in the old country, and served

as an hors d’oeuvre or as a dessert rather than as part of the main meal. Mary would bake her

juustoleipaa in the shape of a two-inch-thick pizza-size disc in the oven until the top began

to acquire a leopardlike pattern of brown spots. Served cold, it was a moist but firm cheese that

squeaked along the teeth when chewed, and so was sometimes called “Grandma’s Squeaky Cheese.” (Alas,

making it required raw milk, and once the USDA began requiring all dairies to pasteurize their milk

before sale, she was unable to make this holiday favorite. These days a commercial version of

juustoleipaa sometimes is sold at places like Trader Joe’s. It is known as frying cheese, bread

cheese -- a literal translation of the Finnish name -- or as, yes, Finnish Squeaky Cheese.)

Roy and Mildred built a large adobe house that shared a

yard with Mary and Billy. They raised two children. Alfred and Josephine had four kids. With two

grandkids only a few steps away and

the rest only a twenty-minute walk down a dirt lane, Mary was heavily involved in the lives of

this next generation, and knew each member well. She in turn was incredibly popular with them. She

doted on them, putting in regular babysitting shifts, teaching her granddaughters her recipes as

they grew older -- though no one attempted to keep up with her in the kitchen. She cooked the

old-fashioned, labor-intensive way, knowing her baking so instinctively

she never measured ingredients, but just grabbed handfuls of this or a dash of that whenever she

judged something was needed. She would bake pulla, the famous Swedish/Finnish sweet glazed braided

eggbread (much like Jewish challah, only spiced with cardamom) two or three times every week until she

was well over a hundred years of age. (Her recipe, as closely as it can be reproduced, can be found

on this website by clicking here.) When the grandchildren were

young she would make custards

even though it meant standing at a stove stirring for an hour straight. She would make

juustoleipaa, a homemade cheese often made with reindeer milk in the old country, and served

as an hors d’oeuvre or as a dessert rather than as part of the main meal. Mary would bake her

juustoleipaa in the shape of a two-inch-thick pizza-size disc in the oven until the top began

to acquire a leopardlike pattern of brown spots. Served cold, it was a moist but firm cheese that

squeaked along the teeth when chewed, and so was sometimes called “Grandma’s Squeaky Cheese.” (Alas,

making it required raw milk, and once the USDA began requiring all dairies to pasteurize their milk

before sale, she was unable to make this holiday favorite. These days a commercial version of

juustoleipaa sometimes is sold at places like Trader Joe’s. It is known as frying cheese, bread

cheese -- a literal translation of the Finnish name -- or as, yes, Finnish Squeaky Cheese.)

During the 1950s, even as Mary continued on as a dynamo -- making rugs from scraps in a loom she

installed in her basement, knitting articles of clothing, and as mentioned above taking a trip to

Finland in 1959 -- Billy was in decline. This was inevitable due to his case of Parkinson’s Disease,

but it was more than that. He wore out in a profound way over the course of the decade. His kidneys

and heart grew weaker, and his mental processing slowed. By the end of the decade William Smeds and

Sons was divided, with Roy keeping the original holdings, and Alfred becoming sole owner of the Reed

Avenue farm. Billy hung on long enough to celebrate his and Mary’s 50th wedding anniversary. He saw

all but the youngest of his grandchildren reach at least eighteen years old, and held each of his

first four great-grandchildren in his lap as babies. He passed away peacefully of heart failure one

evening in the bathtub, age seventy-eight. The date of death was 24 November 1964.

A widow at seventy-one, Mary had one gentleman friend in the next few years but was far too

immersed in her family milieu to disturb the status quo. She lived on in the home she had shared with

Billy (the former Tenhunen residence) until the mid-1970s, when her grandson Bill decided it would be

ideal to renovate the structure. An upscale mobile home was purchased for Mary and a slice taken

out of the bluff to park it permanently where it occupied the corner of an “L” shape composed of

it and the two older houses. Mary moved in on the first of March, 1975. Later that year after

completion of the main portion of the remodelling, Bill and his wife and three children moved into

the old house. The driveway’s cul-de-sac was thereafter almost a little hamlet, with four generations

all within a stone’s throw of one another.

In early 1980 Roy died somewhat prematurely of a heart attack. The following year Bill went through

a tumultuous divorce. All too soon only the two old women, Mary and daughter-in-law Mildred, were left

living on the property. Mary might have reclaimed her former home at that point, but she had always

been easy-going and the house was larger than she needed, so she stayed put. Tenants -- extended

in-laws -- were found to rent the old house, so that younger folk were on site for added security.

Ultimately Mary’s tenure in the mobile home would last a full twenty-five years.

At age ninety-three the Department of Motor Vehicles finally decided

Mary was too old to grant a license to, which did not sit well with her inasmuch as she was still

vigorous. She would sneak into town for groceries for a year or two further until younger relatives

hid her keys from her. Her hearing remained good until her mid-nineties, when an ear infection burst

both eardrums. To get treatment she needed to see a doctor, but first had to find one -- her previous

doctor had retired twenty-some years prior and was not even alive any more! Mary was so robust she

hadn’t needed to see a physician in all that time.

At age ninety-three the Department of Motor Vehicles finally decided

Mary was too old to grant a license to, which did not sit well with her inasmuch as she was still

vigorous. She would sneak into town for groceries for a year or two further until younger relatives

hid her keys from her. Her hearing remained good until her mid-nineties, when an ear infection burst

both eardrums. To get treatment she needed to see a doctor, but first had to find one -- her previous

doctor had retired twenty-some years prior and was not even alive any more! Mary was so robust she

hadn’t needed to see a physician in all that time.

In 1993 a big party was held in Reedley to celebrate her 100th birthday. Visitors came from

far away to attend, including a niece, Maire, daughter of Sofia, all the way from Finland, and

Maire’s daughter Anneli and her husband from Philadelphia, where were just finishing a two-year

sabattical in the United States. By that point only two half-sisters and a half-brother survived

back in Finland, all much younger than Mary.

Mary remained alert mentally. She lived on alone even into her hundreds. She was not yet frail. At age

102 she tripped on a curb and cracked both kneecaps. For other elderly people, this would have been

the beginning of the end, but she refused to stay in bed and let her muscles atrophy and risk

succumbing to “convalescent” pneumonia. Within eight weeks she was getting around in a walker,

and subsequently recovered completely. She was still doing well even two or three years later, but

finally age caught up with her. She grew forgetful, constantly nervous, and less able to take care of

basic household tasks. The saving grace in her situation was that Mildred was so close by, but

Mildred was only twenty years her junior and was beginning to worry she herself was becoming too

weak to assist Mary if she collapsed. In 1999 at age 106, Mary agreed to move into Sierra View

Convalescent Home. However, even then she was in better shape than a great many of the residents

there, and for the initial portion of her tenure helped to push around decrepit eightysomethings in

their wheelchairs.

Finally in the fall of 1999 small strokes began to drain away significant chunks of her lucidity. By

then she

was undoubtedly the oldest surviving person in Fresno County -- certainly in Reedley -- and had

reached the point where things were breaking down despite her still being “healthy for her age.”

She was still so vigorous that when a hip required surgery at approximately Christmastime, 2000,

when she was nearly 108 years old, she made it through the procedure. She lingered on through the

first half of 2001 (too weak, however, to endure the physical therapy that would have been required

to be able to resume walking). Her vitality was a mixed blessing in the sense that

she out-lived her youngest child, Alfred, who essentially died of old age (technically of pancreatic

cancer and Parkinson’s Disease) in May, 2001 at eighty-six. Mary lingered another five weeks --

fortunately never having to know that Alfred had passed on -- and expired 18 June 2001, a third of

a year past her 108th birthday.

Mary was noted for her loving, tolerant nature and non-judgmental attitude. It served her

well and made her the sort of person that, in a fair world, would have lived two or three centuries

instead of one. Asked the secret of her longevity, she answered with complete accuracy, “I mind

my own business and no one else’s.”

Children of Maria Rautiainen

with Vilhelm Smeds

Roy William

Smeds

Joseph Alfred

Smeds

To return to the Smeds Family History main page, click here.

Maria Rautiainen was born 15 February 1893 in Tyrnävä in northwestern

Finland. She was the seventh, eighth, or more likely the ninth-born child of the twelve children of Josef

(nicknamed Juuso) Rautiainen (20 December 1859 - 23 June 1932) and his first wife Marja (aka Maria)

Henriikka Perttunen (5 April 1863 - 9 August 1900). Her name looks like it should be pronounced the way

it is in Spanish, but in Finnish, the emphasis is put on the first syllable, hence it was “MAHR ee ah.”

After coming to America, she shifted to using Mary and Marie. Most of her descendants knew her as Mary, but

she tended to use Marie in documents and when signing her signature and when addressed by her peers.

In the early 1960s the first of her great-grandchildren took to calling her Mumu, a Finnish nickname

for great-grandma, and this was how the younger generations of the clan increasingly knew her during

the final forty years of her life. She would happily answer to any of these names.

Maria Rautiainen was born 15 February 1893 in Tyrnävä in northwestern

Finland. She was the seventh, eighth, or more likely the ninth-born child of the twelve children of Josef

(nicknamed Juuso) Rautiainen (20 December 1859 - 23 June 1932) and his first wife Marja (aka Maria)

Henriikka Perttunen (5 April 1863 - 9 August 1900). Her name looks like it should be pronounced the way

it is in Spanish, but in Finnish, the emphasis is put on the first syllable, hence it was “MAHR ee ah.”

After coming to America, she shifted to using Mary and Marie. Most of her descendants knew her as Mary, but

she tended to use Marie in documents and when signing her signature and when addressed by her peers.

In the early 1960s the first of her great-grandchildren took to calling her Mumu, a Finnish nickname

for great-grandma, and this was how the younger generations of the clan increasingly knew her during

the final forty years of her life. She would happily answer to any of these names. Maria wrote a “letter to all” about her life while in her

mid-nineties. She had been reluctant to write a memoir because her skill at written English was not what

she would have liked, but in 1986 her granddaughter Carol Smeds Krehbiel convinced her to do so by

pointing out that she could write the document in Finnish, and her Finnish granddaughter-in-law Paula

Hakulinen Smeds could translate it. The account has this to say about her childhood: I don’t have many

memories of my mother, just a few of some special occasions. Like once Mother needed to go to Oulu and she

took me along. When we got to the market square, we stopped by a man selling shoes and he offered a pair

for me to try on. Once I had the shoes on, I would not take them off again and Mother ended up paying for

them. However, after we had done some more walking the soles fell off. I don’t remember what we did with

them then. On another occasion Mother was making a dress for Sofia. I don’t remember for what reason she

tried it on me, but of course I did not want to take it off. I was screaming and fighting and remember

hearing Mother say what a bad girl I was to scratch her like that. Father happened to be within hearing

distance, found a twig or two and used them on my bottom. That was the last time I got a whipping.

Maria wrote a “letter to all” about her life while in her

mid-nineties. She had been reluctant to write a memoir because her skill at written English was not what

she would have liked, but in 1986 her granddaughter Carol Smeds Krehbiel convinced her to do so by

pointing out that she could write the document in Finnish, and her Finnish granddaughter-in-law Paula

Hakulinen Smeds could translate it. The account has this to say about her childhood: I don’t have many

memories of my mother, just a few of some special occasions. Like once Mother needed to go to Oulu and she

took me along. When we got to the market square, we stopped by a man selling shoes and he offered a pair

for me to try on. Once I had the shoes on, I would not take them off again and Mother ended up paying for

them. However, after we had done some more walking the soles fell off. I don’t remember what we did with

them then. On another occasion Mother was making a dress for Sofia. I don’t remember for what reason she

tried it on me, but of course I did not want to take it off. I was screaming and fighting and remember

hearing Mother say what a bad girl I was to scratch her like that. Father happened to be within hearing

distance, found a twig or two and used them on my bottom. That was the last time I got a whipping. Annie was happy with her new life. Jack was

employed as a jeweller with Shreve and Company, a large firm, and so the household had a steady

income. In 1906, he became a citizen, giving them added status. The family grew. The one fly in the

ointment for Annie was that she lived so far away from all of her birth kin. In 1910, thanks to their

savings and Jack’s status as a citizen, the couple offered Maria sponsorship and the fare to come to

America. Maria, still only seventeen, was excited by the idea, even though Anna was by then something

of a stranger in that she had not seen her sister for seven years. Arrangements were made and Maria

was on her way, journeying across the Atlantic on a Cunard liner. From her port of entry (unknown at

this time) she boarded a train for the overland portion of the journey. The trek as a whole took

three to four weeks. She arrived in San Francisco in September, 1910.

Annie was happy with her new life. Jack was

employed as a jeweller with Shreve and Company, a large firm, and so the household had a steady

income. In 1906, he became a citizen, giving them added status. The family grew. The one fly in the

ointment for Annie was that she lived so far away from all of her birth kin. In 1910, thanks to their

savings and Jack’s status as a citizen, the couple offered Maria sponsorship and the fare to come to

America. Maria, still only seventeen, was excited by the idea, even though Anna was by then something

of a stranger in that she had not seen her sister for seven years. Arrangements were made and Maria

was on her way, journeying across the Atlantic on a Cunard liner. From her port of entry (unknown at

this time) she boarded a train for the overland portion of the journey. The trek as a whole took

three to four weeks. She arrived in San Francisco in September, 1910. Annie and Jack decided a marriage would be

just the thing to get Mary on the right track and steer her toward the maturity she needed. But

there was a further problem in that so few men of their acquaintance seemed suitable. As Mary put

it in her memoir, I got to know many young Finnish men who stopped by the Temperance Hall and

according to Anna none were any good, except maybe one and he was in poor health. The fact was

that many of the bachelors Annie and Jack knew were alcoholics who, in spite of their participation

in Temperance Hall meetings, were still struggling with their addiction. But then a solution

presented itself. At my first Christmas there, Jack’s brother William came to stay over

the holidays. Anna thought he was one of the best, if not the best. I wasn’t too

interested since he did not even dance and at the time dancing was my favorite entertainment.

Afterward Anna would take every possible opportunity to wonder why I didn’t like Billy.

Annie and Jack decided a marriage would be

just the thing to get Mary on the right track and steer her toward the maturity she needed. But

there was a further problem in that so few men of their acquaintance seemed suitable. As Mary put

it in her memoir, I got to know many young Finnish men who stopped by the Temperance Hall and

according to Anna none were any good, except maybe one and he was in poor health. The fact was

that many of the bachelors Annie and Jack knew were alcoholics who, in spite of their participation

in Temperance Hall meetings, were still struggling with their addiction. But then a solution

presented itself. At my first Christmas there, Jack’s brother William came to stay over

the holidays. Anna thought he was one of the best, if not the best. I wasn’t too

interested since he did not even dance and at the time dancing was my favorite entertainment.

Afterward Anna would take every possible opportunity to wonder why I didn’t like Billy. The house she came to was somewhat small. Four rooms, only

two of which were furnished. There was no electricity and no plumbing. For light, there were oil lamps.

For water, there were buckets. For certain other basic needs, there were chamberpots and the outhouse.

Mary was accustomed to a provincial lifestyle, but she had lived in a big city for over a year and had

expectations as a bride. She told Billy (shown at left) he had to make it possible for

her to get water for cooking without having to fetch it from the well, or she wouldn’t even step

through the door. He saw that she was serious, and spent some of their first day in Reedley setting

up a barrel atop a platform of posts. He filled the barrel with water and ran a hose from the bottom

of it into the house. Gravity then allowed Mary to hand-pump water into the kitchen sink when she

needed it. Having made her point, she laid claim to the home she would live in until Jack and

Annie moved to Reedley.

The house she came to was somewhat small. Four rooms, only

two of which were furnished. There was no electricity and no plumbing. For light, there were oil lamps.

For water, there were buckets. For certain other basic needs, there were chamberpots and the outhouse.

Mary was accustomed to a provincial lifestyle, but she had lived in a big city for over a year and had

expectations as a bride. She told Billy (shown at left) he had to make it possible for

her to get water for cooking without having to fetch it from the well, or she wouldn’t even step

through the door. He saw that she was serious, and spent some of their first day in Reedley setting

up a barrel atop a platform of posts. He filled the barrel with water and ran a hose from the bottom

of it into the house. Gravity then allowed Mary to hand-pump water into the kitchen sink when she

needed it. Having made her point, she laid claim to the home she would live in until Jack and

Annie moved to Reedley.

Roy and Mildred built a large adobe house that shared a

yard with Mary and Billy. They raised two children. Alfred and Josephine had four kids. With two

grandkids only a few steps away and

the rest only a twenty-minute walk down a dirt lane, Mary was heavily involved in the lives of

this next generation, and knew each member well. She in turn was incredibly popular with them. She

doted on them, putting in regular babysitting shifts, teaching her granddaughters her recipes as

they grew older -- though no one attempted to keep up with her in the kitchen. She cooked the

old-fashioned, labor-intensive way, knowing her baking so instinctively

she never measured ingredients, but just grabbed handfuls of this or a dash of that whenever she

judged something was needed. She would bake pulla, the famous Swedish/Finnish sweet glazed braided

eggbread (much like Jewish challah, only spiced with cardamom) two or three times every week until she

was well over a hundred years of age. (Her recipe, as closely as it can be reproduced, can be found

on this website by clicking

Roy and Mildred built a large adobe house that shared a

yard with Mary and Billy. They raised two children. Alfred and Josephine had four kids. With two

grandkids only a few steps away and

the rest only a twenty-minute walk down a dirt lane, Mary was heavily involved in the lives of

this next generation, and knew each member well. She in turn was incredibly popular with them. She

doted on them, putting in regular babysitting shifts, teaching her granddaughters her recipes as

they grew older -- though no one attempted to keep up with her in the kitchen. She cooked the

old-fashioned, labor-intensive way, knowing her baking so instinctively

she never measured ingredients, but just grabbed handfuls of this or a dash of that whenever she

judged something was needed. She would bake pulla, the famous Swedish/Finnish sweet glazed braided

eggbread (much like Jewish challah, only spiced with cardamom) two or three times every week until she

was well over a hundred years of age. (Her recipe, as closely as it can be reproduced, can be found

on this website by clicking  At age ninety-three the Department of Motor Vehicles finally decided

Mary was too old to grant a license to, which did not sit well with her inasmuch as she was still

vigorous. She would sneak into town for groceries for a year or two further until younger relatives

hid her keys from her. Her hearing remained good until her mid-nineties, when an ear infection burst

both eardrums. To get treatment she needed to see a doctor, but first had to find one -- her previous

doctor had retired twenty-some years prior and was not even alive any more! Mary was so robust she

hadn’t needed to see a physician in all that time.

At age ninety-three the Department of Motor Vehicles finally decided

Mary was too old to grant a license to, which did not sit well with her inasmuch as she was still

vigorous. She would sneak into town for groceries for a year or two further until younger relatives

hid her keys from her. Her hearing remained good until her mid-nineties, when an ear infection burst

both eardrums. To get treatment she needed to see a doctor, but first had to find one -- her previous

doctor had retired twenty-some years prior and was not even alive any more! Mary was so robust she

hadn’t needed to see a physician in all that time.