Martintown

The life story of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader is, in

some ways, the story of the place they lived from 1850 onward -- the village of Martin, later to

be called Martintown, which Nathaniel founded. Nathaniel owned and operated the sawmill and grist

mill that were the economic heart of the community. He was the major landowner. He established the

community church. He left his bones in the cemetery that overlooked the mills, bridge, and main

street. He was Martintown. To honor him and his family properly, one must give due attention

to the spot where he and

Hannah resided for the majority of their lives. This page collects some pictures of Martintown

and vicinity, and covers some of the general history of the place above and beyond what you will

find interspersed within the biographies of the family members.

The life story of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader is, in

some ways, the story of the place they lived from 1850 onward -- the village of Martin, later to

be called Martintown, which Nathaniel founded. Nathaniel owned and operated the sawmill and grist

mill that were the economic heart of the community. He was the major landowner. He established the

community church. He left his bones in the cemetery that overlooked the mills, bridge, and main

street. He was Martintown. To honor him and his family properly, one must give due attention

to the spot where he and

Hannah resided for the majority of their lives. This page collects some pictures of Martintown

and vicinity, and covers some of the general history of the place above and beyond what you will

find interspersed within the biographies of the family members.

Martintown, from its founding to the present day, lies just north of the Wisconsin/Illinois state

line in Cadiz Township, Green County, WI. Cadiz (pronounced by locals as KAY dizz) Township takes up

a sixteenth of Green County, occupying the southwestern corner. Its western boundary touches Lafayette

County. Its southern boundary touches Stephenson County, IL. Cadiz Township as a whole was -- and

is -- an incorporated entity, with officials filling governmental roles, but no municipal bureacracy

was ever put in place for Martintown on its own. Martintown is therefore somewhat invisible in the

sorts of reference material that genealogists tend to consult. While some historical

documents such as marriage records, newspaper obituaries, and so forth do use the place-name “Martin”

or “Village of Martin” or “Martintown” -- depending on when and how they were recorded -- far more

just say Cadiz Township, even for events that took place right in the village. That can drive a

researcher a little crazy. Cadiz Township is

a standard-sized township, meaning it is made up of thirty-six square miles divided into thirty-six

one-square-mile sections. Martintown as originally platted consisted of forty-seven acres of the

southeast corner of Section 32, and never grew much larger than that. Each section of a standard

township is 640 acres. That means Martintown takes up less than a tenth of Section 32, and therefore less

than one 360th of Cadiz Township as a whole. It is unfortunate that a specific site should be referred

to in records by a name that also refers to such a relatively huge area. Second problem -- there

actually was a community specifically called Cadiz. No longer extant, it was a crossroads outpost a mile

or so north of Martintown. Though platted in 1846 and briefly qualifying as the hub of civilization

in the immediate area, Cadiz never became a real village and even at its height did not deserve to be

called a hamlet. It was rather less than that. Aside from homes, it boasted only a post office, a store

run out of a home, and perhaps a one-room schoolhouse and a church. Today there is a third problem.

Though the population of Martintown is still two to three hundred, i.e. about as many residents as in its

heyday, this is

no longer a sufficient concentration of people to warrant maintaining a post office. The last delivery

from the old Martintown post office occurred 30 September 1938. Today all residents on the Wisconsin side

of the line get their mail from the Browntown post office, and technically have Browntown addresses even if

they live dead center in Martintown. A small number of residents live in the part

of the town that is in Illinois; these people have Winslow addresses. Depending on what resource you

use to try to locate Martintown on a map, you may come up empty, as if Martintown has vanished from the

face of the earth. But not only is the place still there, it is still recognizably the setting shown in

the pictures on this page.

Many of these images date from the peak of Martintown’s prosperity and activity, a period which lasted

from the 1880s up through the first decade of the 20th Century. Photos from before that generally do

not exist. Photos made after that do not capture the village as Nathaniel and Hannah knew it. The

community they knew went through three phases. Another way of putting it is, Martintown had three

births.

First came the initial settlement in 1850. At that point, the place was little more than a crossroads

or manor holding, consisting of the Martin home, the sawmill, and a handful of other residences such as

that of Nathaniel’s initial partner Edwin Hanchett. For the next seven years, until the bank panic of

late 1857, expansion was rapid. A flour mill was added beside the sawmill in 1854, becoming Nathaniel’s

new focus while his brother Isaiah handled the sawmill. A durable bridge over the Pecatonica River was

finished in 1856. It was during these good times that Nathaniel and Hannah established themselves

in the big white residence that you will see in the images below, moving out of the modest dwelling

Nathaniel had thrown up in 1850.

The bank panic and the Civil War dimmed the optimism of the community. Only a few important developments

occurred during those years, for example the opening the village post office in 1865. The second-birth

period began in the late 1860s. America as a whole was enjoying an economic boom period brought on by the

end of the Civil War and by the commitment by government and industry over the next eight years to construct

a nationwide network of railroads. Prosperity became so widespread that it seemed prudent to rise to the

occasion and develop Martintown accordingly, in expectation of the opportunities that access to the outside

world by rail would afford. In 1868, Nathaniel hired a surveyor, a man with the surname Dodge, and

had the village platted, a formal step that defined streets and blocks that still exist

today. The following year saw the opening of several retail establishments, most of them along Bridge

Street. The rapid growth meant the village suddenly had a semblance of a downtown, though its length

could be walked in a minute or so.

Unfortunately, the economic surge was fueled in part by speculation. When railroad-construction subsidies

ended and investors suddenly became worried their stock was losing value, the country plunged into the

event that later would be called the Panic of 1873. That name is deceptive because it implies the crisis

lasted only one year. It was actually a deep and extended depression on a scale that would hold the record

for the worst in U.S. history until the Great Depression of the 1930s came along. It consumed the rest of

the 1870s, and in Europe lasted well into the 1880s. The early-1870s plan to bring a railroad line to Martintown

failed for lack of investment money. The woolen mill remained unfinished. Horatio Woodman Martin and his

brother-in-law Jacob Hodge sold their general store. Martintown’s growth and vigor was subdued for about

fifteen years.

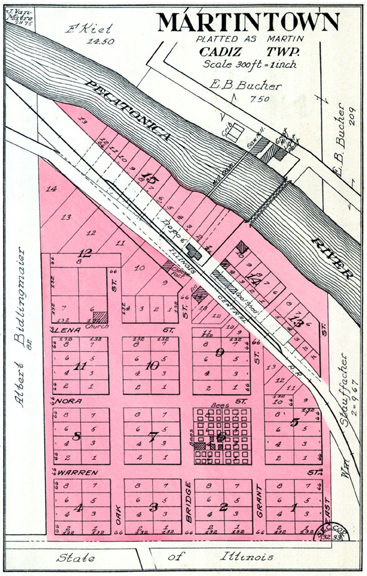

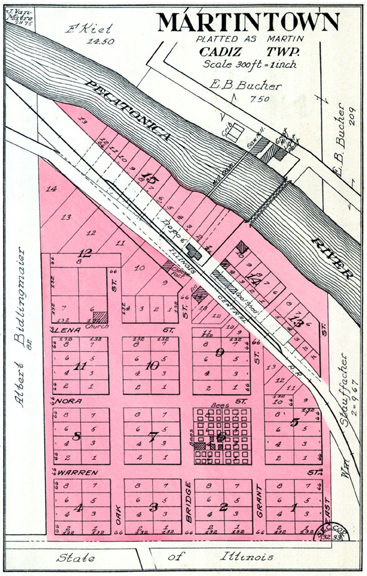

With the installation of an Illinois Central Railroad depot in 1888, things moved into high gear again. Among

the changes was the town name. The depot was given the designation Martintown rather than Martin. Somewhat

surprisingly, the locals embraced the change. Once the post office was renamed Martintown on the first of

June, 1892, there was no going back. The village had now become the place reflected in the 1918 platt map

shown above left, one of a number of revisions of the original 1868 platt map. (Aside from the names of

landowners, there are very few differences from the village that existed during the latter part of

Nathaniel’s lifetime. One minor difference is the block filled with small rectangles. The rectangles

represent bee boxes that stood there in the late 1910s. The beekeeper responsible may well have been

Hannah’s nephew Elmer Eveland.)

As you can see (depending on how clearly you can make out the details of this somewhat low-resolution

version of the platt map), even though the sawmill and flour mill were the economic heart of the

village, they were not not in fact located at the geographic center. The mills were on the north side

of the river. The majority of the town was on the other bank, and it was this area that contained all

of the other businesses with the exception of the quarry, which lay on the same side and slightly

west of the mills. In this peak period Martintown was made up of dozens of residences, the sawmill,

grist mill, and woolen mill, the church, the railroad depot, a cheese factory (which doubled as a

creamery), an elementary school, an undertaker’s parlor, two general merchandise stores -- the post

office was operated out of one of these -- and various shops including those of a wagon maker, a

blacksmith, and a cabinet maker.

After the heyday, the dwindling occurred slowly but progressively. As early as 1905 Illinois Central

began talking of closing

the depot for lack of enough activity, a decision contemplated in part because the arrival of telephone

service to local businesses and homes meant far fewer customers would be showing up at the telegraph

counter at the depot -- telegram income was one of the prime justifications for keeping a

station agent at a depot. In fact, the closing of the depot occurred decades later, but it did eventually

happen. And bit by bit, much of the infrastructure described in

the paragraph above was lost or changed. The mills are long gone. The Bridge Street bridge no longer

exists, nor does the railroad bridge. These could not have remained in place once County M Road

was modernized in the middle of the Twentieth Century. County M Road now does not make the “L” bend

shown at the top of the map; now it continues straight across

the river and climbs the hill just west of the church to join the road to Winslow, a fragment of

which you can see at the bottom of the map. The new road wiped out structures and streets in the lower

left portion of the original town. Elsewhere structures were never rebuilt after being lost to fires or

floods. Others fell victim to delapidation over the long stretch of years. At least one, the woolen mill,

was eventually cannibalized for its lumber. The community is no longer as dense as it was in the 1890s,

with many vacant lots. (It is the newer homes added off to the east that keep the population about the same

as in the glory days.) All retail businesses ceased and the only public building that survives as

a public building is the church. However, Nathaniel and Hannah would still know Martintown as Martintown if

they could see it today. The basic grid of streets and blocks remains. The church, the cheese factory, the Martin

schoolhouse, and the old train depot are still standing, although the latter three have been converted to

residences

and the depot is now located closer to the corner of Bridge Street and the river. Most important, some

of the homes are occupied even now by members of the Martin/Strader clan.

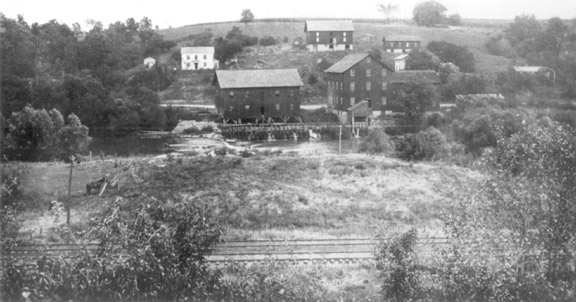

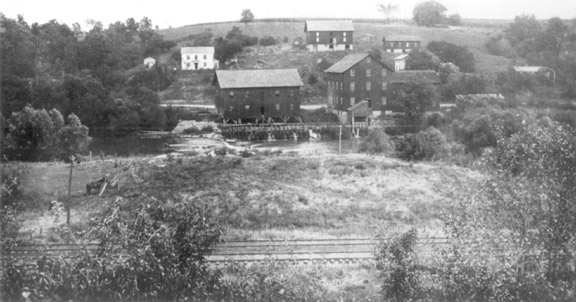

Looking north, this view, probably taken in the 1890s or early 1900s, shows Nathaniel’s

stomping grounds as they looked during his lifetime. Note the rock dam across the Pecatonica River,

piling up the water to operate the sawmill and grist mill -- the largest buildings shown. The

white house immediately upslope from the dam is the residence of Hannah and Nathaniel. Along the

hilltop above the mills is the family cemetery, though it is almost impossible to make out the

tombstones in this photo, particularly at the somewhat low resolution used for internet purposes.

The large building on the hillside is a horse barn, the slightly smaller but similar structure is

a cow barn. The house just below the cow barn, mostly hidden behind trees, is the home of Horatio

Woodman Martin and his family. The other house to the right, also somewhat hidden in foliage, is

the home of Emma Ann Martin and Cullen Penny Brown, though at the time the picture was taken the

couple and their younger children were usually to be found in Arkansas and the main occupants were

Emma’s daughter Lena, husband Frank Opal Hastings, and their kids. Martintown itself is out of view

to the right of where the photographer set up his camera. Today very little of what is shown here

still exists; however, the foundations of the three houses have been preserved as the basement

level of new residences.

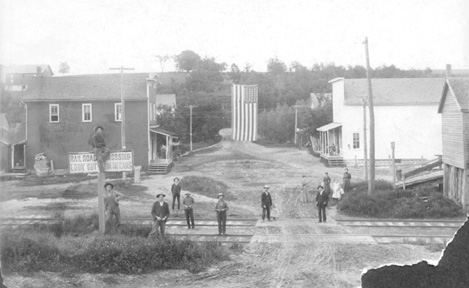

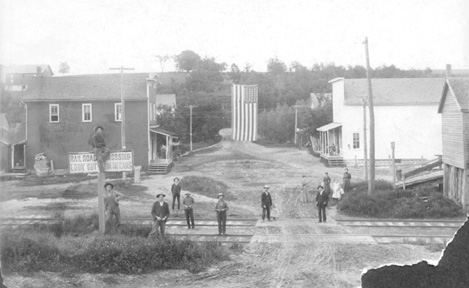

This view was taken from within the town itself, again facing the river. (You can see the building

on the upper left is the horse barn that appears in the upper center of the first picture.) This is

the “bent” part of Bridge Street, the original main street. The bridge itself is here, but is mostly

obscured behind the flag. The depot is just out of sight to the left. The utilitarian building right

on the track, mostly out of view to the right, was the coal house. The mills are out of frame to the

left. The poles and strung lines are for the depot’s telegraph service; at this time the town did not

have electrical power. The scene shows a number of vacant lots; this undoubtedly reflects structures

lost in fires -- one such fire consumed much of the business core of the village. This photo must have

been taken around 1902 to 1905, because the little girl in the white dress is surely Nathaniel and

Hannah’s youngest granddaughter Vivian Blanche Martin, who appears to be about the same age as in the

photograph displayed on her father Horatio Woodman Martin’s page

(click here) of family and neighbors in the town’s limestone

quarry, which is known to have been taken in 1904 or 1905. Here four people have been identified so

far. Vivian is one. The woman in the street (her dress blends in with the background,

so look closely) is Laura Hart Martin, wife of Horatio. The mustachioed man on the tracks in front of

the group that includes Vivian and Laura must be Horatio himself. Two figures to the left of Horatio is

John Warner, the husband of Eleanor Amelia “Nellie” Martin.

This image and the one below were used for postcards and were scanned directly from surviving specimens

of those postcards. This scene captures the Martintown mills in the deep of winter. The Pecatonica

River is nearly frozen over. With the foliage of the trees absent it is much more apparent that the mills

consisted of three large buildings, not two as it seems in the top picture.

And here we have a similar view taken in summer. This especially fine view of the mills clearly shows

how the dam held back the flow of the Pecatonica to create the mill race that powered the waterwheels. The

portion of the river in the foreground can be seen to be lower than the upstream part of the river in the

background. The top portion of the Martin home is visible peeking up above and to the right of the

mills.

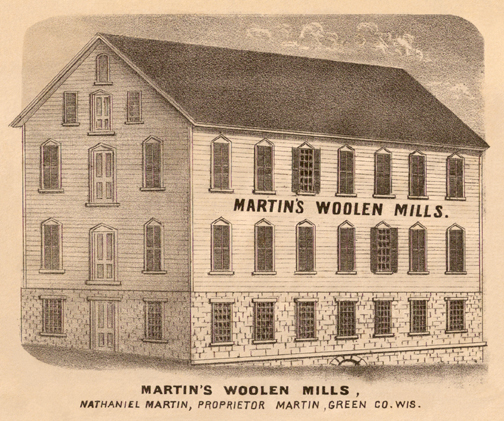

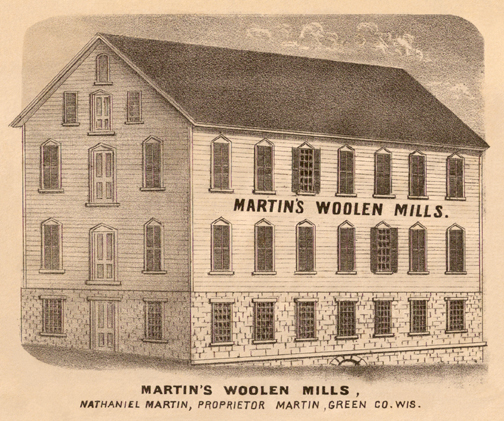

This drawing of the original Martin woolen mill was probably not made from life. It was probably a

concept sketch meant to show what the woolen mill would look like once it was built. If so,

perhaps the artist was the architect; otherwise, he was a freelancer hired by Nathaniel Martin so

that he would have a picture with which to tickle the interest of outside investors. However, concept

sketch or not, eventually the structure was made into reality, and from all accounts, seems to

have strongly resembled what you see here.

Precisely when the building was erected is not quite clear. The origin of the woolen mill has grown

murky. One reason it is difficult to nail down the particulars of its history is because the outer

shell of the structure stood empty for decades. No employees were ever hired, so there was no

“original crew” who could later recall coming in for the first day of operation and smelling the fresh

varnish and running their fingers over the shiny, brand-new looms. A two-page essay on the history of

Martintown written in the late 1930s by Mrs. Vilas Heise provides the best clue. Mrs. Heise indicates

that once the Martin sawmill and flour mill proved to be successful, Nathaniel set in motion a scheme

to add a woolen mill. This would seem to indicate the building was erected in the late 1850s. Two

scenarios seem likely. Either the enterprise was in development when the bank panic hit in the autumn

of 1857, or construction was initiated a couple of years later as part of Nathaniel’s strategy to

recover from the 1857-58 slump. The woolen mill building was definitely in place by the early 1860s,

because Mrs. Heise mentions the huge indoor space was the venue for a party (or parties) celebrating

the return of local young men from their military service in the Civil War. Also, a letter from Cyrus

Woodman written 3 June 1861 to Nathaniel recommends that Nathaniel purchase a new stove -- Woodman was

apparently an agent for Franklin stoves -- for the “new mill,” which could only have been a reference

to the woolen mill. The context of the letter implies the building was already in existence, but still

missing such essentials as a means of heat.

In 1887, the pending establishment of Illinois Central Railroad’s Freeport, Dodgeville & Northern route

doomed the structure. The parcel of land on which it stood, located directly across the river from the

other two mills, was needed for the easement. If the building had been left standing, the new trestle

bridge and the tracks could not have been installed along the preferred survey line. So it was

demolished. The razing must have been completed by November, 1887 at the latest because by the end of

that month or the very first day or two of December, the tracks were in place. The construction train made

it to Winslow 26 November 1887, where the locals there gathered 1500-strong to witness the long-awaited

development and throw a feast for the workers, as confirmed by newspaper coverage. A follow-up article

reveals that by the fifth of December, the crew had completed the line as far as a mile past Martintown.

In thirty years of existence, the building had never achieved its intended purpose and become a working

woolen mill. Over such a long period the shell surely must have served to do more than to keep the rain and

glare off village denizens as they held parties. It probably was utilized as extra storage space for the

lumbermill and flour mill. Why the wasted potential? What happened? The answer was not included in the

Heise essay. It was one of many subjects not fully developed. Mrs. Heise, a young woman in the late 1930s,

composed her article after asking a few oldtimers of their memories of early Martintown, and then only

presented some of the highlights of what had come from those interviews. There are any number of reasons

why the project might have hit a snag. The bank panic surely played a role, drying up credit just as the

looms needed to be purchased, and dimming the hopes that there would be lots of customers with cash in hand

to pay for the textiles the mill would have produced. After that, there must always have been something

standing in the way to make the investment seem impractical. One likely factor is that the mill would have

needed to import a substantial amount of raw material from outside the area, and then ship finished goods

out with equal efficiency. That meant railroad shipment. But early attempts to bring a rail line to

Martintown failed, and everything was put on hold until 1888. The 1884 volume, History of Green

County, Wisconsin, confirms the long wait. The book contains this line: “The village of Martin ... in

the summer of 1876, had within its limits twelve families, a store and post-office, N. Martin’s mills,

including an unfinished woolen mill, and Haase’s furniture factory.”

It is ironic that the arrival of that long-anticpated rail service was what caused the first building to

be torn down. This was not quite the end of the story, though. Mrs. Heise’s essay goes on to say that when

Illinois Central offered to move the building, Nathaniel said no, he would take care of it himself, upon

which he proceeded to salvage the building material. These parts were incorporated into

a new building two blocks southeast of the church. At first, Nathaniel said he intended to purchase

equipment and finally establish the factory after all, now that the village had ready access to suppliers

and markets. But another essay about Martintown, this one written some time during Nathaniel's final

years (i.e. written no later than the beginning of 1905), reveals that he changed his mind during

construction. The new building was instead redesigned to house a store and living quarters. Nathaniel

gave the property to a daughter (the source does not say which daughter), who only kept title to it for

a short time before selling it to others.

Nathaniel’s decision not to open the mill after all reflects his business savvy. In the late 1850s, it

had been a sensible idea, but by the late 1880s, the nation’s textile mills were already becoming

centralized. Any operation in Martintown would have found it difficult to produce fabric and/or

finished goods that could complete with those brought over long distances from places where

they could be manufactured at far lower costs. As for the second building, it was not particularly

practical for other use, either, and it remained standing a few decades at most. By the

time Mrs. Heise put words to paper in the late 1930s, all that was left was the

foundation. The building had once again been demolished, its lumber finding new purpose in barns west

of town and in a house owned -- at the time of the essay’s publication -- by Ernest Mani.

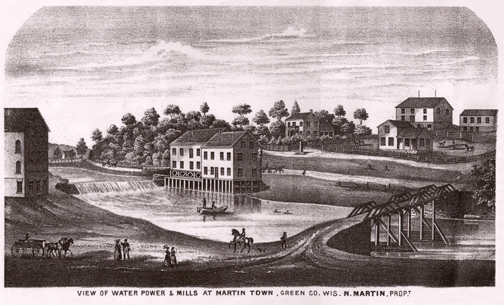

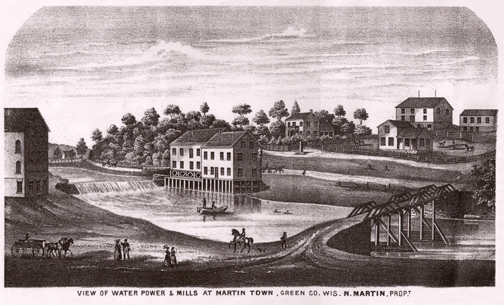

This may have been another woolen mill concept sketch, perhaps even by the same artist, but chances

are it was drawn from life -- though with a certain amount of stylistic license -- after the woolen

mill shell had been completed. (It is the large building on the left.) This was Martin as it

looked some time between 1856 and 1868. The time frame is possible to determine because the drawing

includes the original bridge, built in 1856, yet does not show the grid of streets laid out in 1868.

Note that there are still only two mill buildings on the far side of the river. It is unknown just

when the third building was added.

The Martintown mills in the 20th Century, while they were still standing. This was taken from the

house side. All other views of the mills found so far were taken from across the river.

The Martin family cemetery is near the top of the hill just north of the village. Shown here in late

2005, it is as you can see currently surrounded by woods. Now, as in the past, it is on private land.

Much of the farm is taken up by a large field alternately planted in alfalfa and corn to supply feed

for the small on-site dairy. The cemetery lies near the edge of the field, separated from it by

a gate and thin buffer of

trees. It has been almost a century since the farm was owned by members of the Martin/Strader clan, but

subsequent owners have treated the cemetery with respect. Local citizens, historical society volunteers,

veterans groups, and so forth see to it that the weeds are kept under control. All in all, it is in good

condition for such a long-unused small family cemetery, but it is a fact that the passage of time has

affected the condition of the headstones. Most are no longer perfectly vertical. Two have come fully

loose from the earth. A few are extremely weathered, and one or two are getting to be almost illegible

unless one already knows what the inscriptions say.

In the early or mid-1850s when the site was chosen to become a graveyard, pioneer land-clearing efforts

had left the view unimpeded in every direction. The spot therefore provided a broad view of the surroundings

and was accepted as a contemplative setting appropriate to a resting place of the dead. Its proximity to the

family home (and later, homes plural) meant survivors only needed a few minutes to walk uphill and place

flowers on the graves or otherwise pay their respects. Local lore says that Nathaniel chose the spot for

another reason. In 1848 (or about then), Hannah’s sister-in-law Elizabeth and her husband Jerry Frame

were fording the Pecatonica right at the spot where the village of Martin would be founded. Their

three-year-old daughter Anna Frame fell out of the wagon and drowned. The little girl’s body was buried at

the top of the hill. When Nathaniel decided to plot out a graveyard for the village, he chose to put it

where Anna had been buried. Or so the story says. There is no first-hand source available that proves the

tale, and there is no gravemarker for Anna. The account seems credible, but it has been told so many times

over the years and in such vaguely remembered fashion that sometimes the child who drowned is described as

a son of Nathaniel and Hannah. Their son Linky did drown, but not until he was eighteen. Son Charles died

at three and it may have been by drowning. Perhaps the stories became concatenated and mangled. Assuming

Anna Frame’s burial was not the first, then the first was infant William Martin, who died in the summer

of 1854 on the same day he was born. The subsequent burial was that of Nathaniel’s father James Martin,

who died of old age in the autumn of 1856.

All of the surviving gravemarkers -- believed to be all

that ever existed -- are devoted to close

Martin family members. The group includes Nathaniel and Hannah themselves, nine of their children, three

of their grandchildren, Hannah’s nephew Elias Frame, and Nathaniel’s father James Martin. Most of these

gravemarkers can be seen in this view. The large stone in the foreground is that of Nathaniel and Hannah.

Their names appear on the front of the stone. Inscribed on the sides and reverse are the names of children

William, Charles, Christie Belle, James Franklin, and Hannah, all of whom died very young. (The other child

who died young was Alice Adelia Martin, who was buried elsewhere, location unknown. She died before the

Martin cemetery had been established.) The other large marker is that of Mary Lincoln “Tinty” Martin Bucher,

its size reflecting the intent that her husband Elwood Bucher would be buried alongside her one day. But in

the end, the place where his name and stats would have been etched was left empty, because he was buried in

Rock Lily Cemetery in Winslow along with other Bucher family members, having moved Tinty’s body and casket

to that locale some time in the 1920s. The medium-sized marker is that of Jennie Edith Martin Hodge. Leaning

against it is the headstone of Abraham Lincoln “Linky” Martin. The latter stone’s original placement is now

guesswork. The same applies to the headstone of James Martin, shown here leaning against a tree. In the

distance, at the far edge of the cemetery, you can make out the bluish marker of Elias Frame (close-up

view shown at right), whose burial here was a matter of happenstance. Elias had moved away from the area

approximately thirty years before his death in 1901. In the early 1890s he had settled in Tulare County,

CA. He died unexpectedly during a visit to see his relatives back in Green County and the decision was made

to bury him in the Martin graveyard rather than ship his body all the way to California. Not visible in

this view are the markers of Horatio Woodman Martin, Fay Horatio Martin, Ida Ellen Warner, and Minnie Edna

Brown. Fay was

the very last person buried on-site. Once Nathaniel and Horatio passed away in quick succession in 1905

and 1906, the practice of regular burials here ceased. Naturally Hannah was laid to rest with her husband

when she died in 1919, but she was the last until her grandson Fay made arrangements to be interred among

his kinfolk. Fay left instructions that he be put in the ground dressed in his overalls, and his wish was

obeyed. Fay died in 1965, so his burial represented the first time the cemetery had welcomed a new occupant

in forty-six years.

All of the surviving gravemarkers -- believed to be all

that ever existed -- are devoted to close

Martin family members. The group includes Nathaniel and Hannah themselves, nine of their children, three

of their grandchildren, Hannah’s nephew Elias Frame, and Nathaniel’s father James Martin. Most of these

gravemarkers can be seen in this view. The large stone in the foreground is that of Nathaniel and Hannah.

Their names appear on the front of the stone. Inscribed on the sides and reverse are the names of children

William, Charles, Christie Belle, James Franklin, and Hannah, all of whom died very young. (The other child

who died young was Alice Adelia Martin, who was buried elsewhere, location unknown. She died before the

Martin cemetery had been established.) The other large marker is that of Mary Lincoln “Tinty” Martin Bucher,

its size reflecting the intent that her husband Elwood Bucher would be buried alongside her one day. But in

the end, the place where his name and stats would have been etched was left empty, because he was buried in

Rock Lily Cemetery in Winslow along with other Bucher family members, having moved Tinty’s body and casket

to that locale some time in the 1920s. The medium-sized marker is that of Jennie Edith Martin Hodge. Leaning

against it is the headstone of Abraham Lincoln “Linky” Martin. The latter stone’s original placement is now

guesswork. The same applies to the headstone of James Martin, shown here leaning against a tree. In the

distance, at the far edge of the cemetery, you can make out the bluish marker of Elias Frame (close-up

view shown at right), whose burial here was a matter of happenstance. Elias had moved away from the area

approximately thirty years before his death in 1901. In the early 1890s he had settled in Tulare County,

CA. He died unexpectedly during a visit to see his relatives back in Green County and the decision was made

to bury him in the Martin graveyard rather than ship his body all the way to California. Not visible in

this view are the markers of Horatio Woodman Martin, Fay Horatio Martin, Ida Ellen Warner, and Minnie Edna

Brown. Fay was

the very last person buried on-site. Once Nathaniel and Horatio passed away in quick succession in 1905

and 1906, the practice of regular burials here ceased. Naturally Hannah was laid to rest with her husband

when she died in 1919, but she was the last until her grandson Fay made arrangements to be interred among

his kinfolk. Fay left instructions that he be put in the ground dressed in his overalls, and his wish was

obeyed. Fay died in 1965, so his burial represented the first time the cemetery had welcomed a new occupant

in forty-six years.

From the early 1880s to 1890, Martin cemetery appears to have doubled as the village graveyard, even

though most locals who lost loved ones during that span chose to bury them in the larger cemeteries that

could be found within a few miles, such as Rock Lily in Winslow or Old Cadiz (aka Pioneer), Saucerman,

and Kelly/Franklin in Green County. No identifiable markers exist for these “extra” burials. It is

possible the graves never had markers, at least not ones meant to endure until the 21st Century. The total

number of people buried in the cemetery is therefore uncertain, but it is doubtful there are many

unaccounted for. It could be the number consists only of these five individuals whose names and birth/death

stats are known from courthouse records: Josiah Brown (15 March 1818 - 2 April 1883). Josiah may

have been the father-in-law of Emma Ann Martin. The identity of Cullen Penny Brown’s father is not certain.

Cullen was raised by grandparents. Josiah Brown was of the right age to be Cullen’s father, and it would

make sense that Cullen’s father would be interred in the Martin plot. However, it is just as likely Josiah

was a member of a Cadiz Township family named Brown. Perhaps Josiah was a relative of Laura Hart, the wife

of Horatio Woodman Martin. Laura’s maternal grandmother was Sarah

Ann Brown. Mrs. William Edwards, died 30 June 1885 at age 48. William Edwards was for

thirty years the proprietor (at first in tandem with partner Watson W. Wright) of Martintown’s main general

store, having been a miller at the Martin flour mill for a long stretch before that. His wife’s maiden name

was Nancy Shull. Better known in the tightknit community of Martintown as Nannie

Edwards, she was a daughter of Jesse W. Shull and Melissa Van Matre, who were among the very earliest settlers

of Cadiz Township. Jesse was in turn one of the first white men to frequent the general area, having been a

trader in Galena, Jo Daviess County, IL and in the 1820s having founded Shullsburg, Lafayette County, WI with

Melissa’s brothers. Jesse brought the family to Cadiz Township in about 1837 when Nancy was a tiny infant,

having acquired the farm of George Lot, the very first white settler of the township. Nancy’s slightly

younger sister Marietta was quite possibly the first white baby born in Cadiz Township. Nancy herself was born

on a steamboat on the Mississippi River near Kentucky, possibly during a trading expedition. Sies

Loomis (5 July 1810 - 14 April 1890). Not quite identified, but surely this was an individual connected to

Cornelius William Loomis, long one of the farmers of Cadiz Township. Cornelius was not the only Loomis to

settle in the township in its pioneer days and it makes sense that a kinsman would be buried in Martintown.

Ironically Cornelius himself, who died in 1883, was buried instead in Michael Cemetery near Browntown.

Baxter Tyler, died 27 August 1885 at age 3 years. Baxter, son of Civil War veteran Nathan Tyler, was a

nephew of Dayton D. Tyler who worked in the Martin sawmill and later was a partner with Nathaniel’s

son-in-law John Warner, producing custom hardwood lumber at Dayton’s own sawmill on his farm, the former

Saucerman homestead, north of Martintown. Baxter’s grave is now at Rock Lily Cemetery with his parents.

Glen Smith (died 24 December 1889, age 3 years. Glen was a

nephew of Lavina Watson, wife of Elias Martin. He was the only son of William G. Smith and Viola Watson, a

couple who were closely connected to the Martin/Strader family as neighbors and friends. William and

Viola remained on their Cadiz Township homestead until 1916, when they retired to

Monroe. Viola was in the midst of a pregnancy when Glen perished. She bore a daughter, Flossie, less than

four months after Glen’s death. Flossie was William and Viola’s only other child, and would go on with her

husband Farmer R. Bast to take over the homestead when William and Viola retired. (Yes, Flossie’s husband really

was a farmer named Farmer.)

When the Pecatonica froze completely, the ice could get quite thick. Ice skating was popular at such

times. A family tale tells of an occasion in the early 1900s when Nathaniel’s grandson Bert Warner

and grandson-in-law Fred Philo Hastings skated all the way from Martintown to Scioto Mills, a distance of

some ten miles. Here is a view from about 1912 of local teens enjoying an excursion. (Don’t be deceived

into thinking these are adults. The old fashioned type of winter wear makes them seem older. Some of the

individuals shown here are at most thirteen years old.) From left to right, Charles Cline, John Cecil

Hastings, Leland “Hap” Hastings, Earl Wickersham, Frank McMillen, Ernest Leck, Edgar Kincannon, Minta Van

Matre, Emma McMillen, Ava Van Matre, Nora Smith, Christie Van Matre, Merle Gage, and Stella Cline. (The

individual hunkered down on the ice between Minta and Emma is not identified.) Edgar Kincannon and Emma

McMillen would become each other’s spouses a few years later.

This view is centered upon the original Martintown depot. The carpenter (or contractor) responsible

for the construction was William Leverton, a local man who built this and half a dozen other local depots

(the Winslow one among them) during the 1880s as the so-called Dodgeville line was established. The building

was actually quite near much of the town, though this angle makes it seem isolated. In the background,

across the river, is the family home, and the mills, always a landmark part of the village, are seen once

again. The gouges in the hillside are the result of quarry activity. This picture, reproduced from a

postcard, had “In Spring Time -- Martintown, Wis.” written in the margin in a child’s handwriting. The

child was probably Nathaniel and Hannah’s great-granddaughter Gladys Beryl Spece.

Here is a class picture of the pupils of the Martin School in the mid-1890s. This photo comes from the

collection of Albert Frederick Warner, son of Nellie Martin and grandson of Nathaniel and Hannah. He and his

brother Walter Clare Warner are the two boys (left to right) shown standing immediately in front of the

right-hand shutter of the window, in the back row of pupils. Bert wrote on the back of the print that the

date was 1896 or 1897. Bert would have been twelve that year. He wrote that note while in his nineties and

perhaps his recollection was hazy; he seems younger than twelve in this view. Also, the flag has forty-four

stars. Utah became the forty-fifth state at the beginning of 1896 and the school would surely have obtained

a new flag by that summer, if not sooner, so we can rule out the 1897 date. 1894 seems about right. The

teacher standing at the left is Jennie Tyler Steere (1866-1938). She was a daughter of Dayton D. Tyler,

the sawyer mentioned above in the text about the cemetery. (The Tyler clan, along with the Lynch clan, moved

to the Winslow/Martintown area from Coshocton County, OH in the late 1840s and early 1850s in great numbers.

Lavina Watson, who would become the wife of Elias Martin, was part of this group, being the daughter of

Mary Lynch. Jennie’s sister Mary Tyler married Lavina’s younger first cousin Simon Peter Lynch, who went on

to be one of the prominent citizens of the district for many decades around the turn of the century.) Alas,

Bert only identified himself, Walter, and Jennie. However, the group surely includes some of Nathaniel and

Hannah’s other grandchildren, who are known to have been students at the school that year. Those would be

Horatio’s sons Nathaniel and Fay Martin and Tinty Martin Bucher’s children Claude, Arley, Rose, and

Blanche Bucher, and Bert’s older brother Cullen Warner. Careful examination of the full-resolution scan

and comparison with other family photos

allows these educated guesses: Nathaniel “Natie” Martin is the boy under the flag second from right from

Jennie in the back row. Claude Bucher is the boy to the right of Walter Warner. Arley Bucher is the girl

on the far right of the middle row. Cullen Warner is the round-headed boy in the middle row below the

right lower corner of the flag.

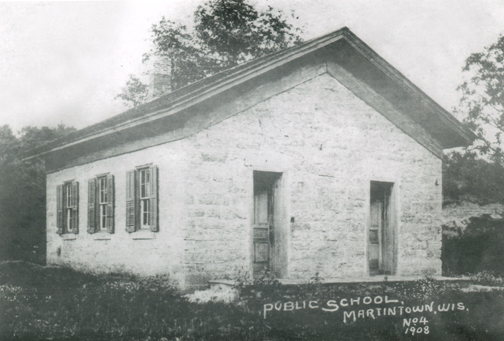

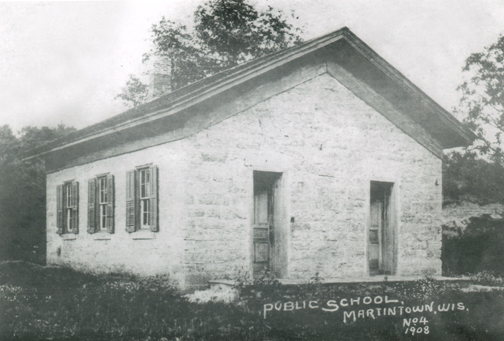

This is what Martin School looked like in 1908. It could very well be the one built in 1856 or 1857

when Martintown had become home to enough families with young children to need a structure this size.

The original village-of-Martin schoolhouse was a twelve-foot-square shack where Belle Bradford taught

earlier in the 1850s, her pupils consisting of the eldest Martin kids (just Elias, Nellie, and Jennie)

and a similarly small number of the offspring of village gunsmith Tracy Lockman. Amazing though it may

be, if you visited Martintown today, you could find this building still in place. After it ceased being

a school the structure was converted into a private residence. It is currently the home of a former

brother-in-law of a descendant of Nathaniel and Hannah.

Here is a group of local boys in 1919, all of them pupils at Martin School. The teacher that

year was Lillian Gempeler (1890-1982). From left to right in back: Aubrey Davis, Elmer Kuhl, Dwight Buss

(hanging upsidedown), Ernest Hastings, Earl Davis. From left to right in front: Joseph Reynolds, Hobart

Lehman, Alton Kiel, Ted Kline, Lewis Cecil, Burton Eells, Estel Buss. None of their kids would have the

chance to attend Martin School because of its closing. In the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s, schoolkids of

southern Cadiz Township attended Rush School. That institution, originally founded by Hannah Strader

Martin’s brother-in-law Henry Rush, was also a one-room school. After Rush School closed, local kids had

to be bussed about twenty miles west to Gratiot, WI.

One reason we have top-notch views of Martintown from the early Twentieth Century is due to the career

of Buel Henry Dingman, who established B.H. Dingman Publishers in Plymouth, WI in the 1890s and dedicated

his business to creating photographic postcards of scenes of Wisconsin. Eventually he had arrangements with

nearly twenty photographers and his catalog included between eight and two dozen scenes of almost any

community of Wisconsin, even tiny ones like Martintown. In fact, chances are good some of the other postcard

scenes shown on this webpage were Dingman productions. Certainly that is true of this one from 1909. The

photographer captured the shot by standing on the bridge and aiming his lens south toward the church. This

was scanned from a postcard that was cut down to fit inside an envelope and mailed some time in the 1940s or

1950s by a Wisconsin-based relative (probably Mary Emma Warner Hastings) to Nathaniel and Hannah’s

granddaughter Ethel Brown Cannon of Texas, or possibly to her sister Lulu Brown Seay, also of Texas. The

postcard having been purchased by the sender at the Martintown general store all the way back in 1909 or

1910. (Do not be led astray by the description on the image -- a feature of the original item -- that refers

to the Martintown dam and mills. The photographer was facing away from the dam and mills.)

This and the image above, studied in tandem, go a long way toward giving a sense of what the village

looked like in the early 1910s. This shot is dated 1914. The photographer was Alfred Charles Cline, who

strangely enough was not a member of the well-known Cline family of Martintown and rural Cadiz

Township. Better known as A.C. Cline or as Charley Cline, he was only eighteen years old in 1914, and

had only just started dwelling in Martintown as an employee of Illinois Central Railroad, having moved

there from his childhood home in Richland County, WI. His “young adventurousness” may well have been a

factor in the creation of this photo, because the angle demonstrates that it is -- as it says on the

print -- a bird’s eye view. There are two possibilities. Either Charley climbed a tall tree on the Van

Matre property (the parcel just west of the Martin estate, on the north side of the river) or he went

up in a hot-air balloon. The 1910s was an era when circuses were still extremely popular and when one

would come to Winslow and Martintown, they are known to have sometimes been set up in the flat area

along the river just west of Martintown. Such circuses in the 1910s often featured tethered balloon

rides. Charley may have taken advantage of the opportunity to get a photo of his new home. Among the

highlights here: 1) The church is prominent on the right. 2) The large white building near the center

is the general store. Operated by Nathaniel and Hannah’s grandson John Martin Warner until just a few

years earlier, it was in 1914 being overseen by Elwood Bucher’s brother Tom. In the mid-1920s, the

proprietors would be Nathaniel and Hannah’s great-grandson Leland Francis “Hap” Hastings and his

wife Hulda. (For more about Hap and Hulda’s tenure, see the “general store robbery” sequence of photos

below.) 3) You'll easily spot the water tower, used to top off the locomotive’s tanks when trains

paused at the depot. The depot building itself is to the left of the tower along the track, but is

mostly hidden by trees; from our angle it is situated directly below the general store. 4) If you look

slightly to the right of the water tower, you will see the creamery. 5) One of the advantages of the

bird’s eye view is that is reveals how the railroad track -- long since torn up and gone away -- curved

off toward the south as it swung through the eastern portion of the village, heading off to Winslow.

One of the houses along the route, quite distinguishable in the high-resolution version of the scan,

was home for many decades of the Twentieth Century to Nathaniel and Hannah’s great-granddaughter

Leah Merle Hastings Schumacher and family.

This image was also printed on a postcard and was scanned from one sent from Martintown to Fresno

County, CA by Fred Hastings to his first cousin Alie Spece. It portrays the wreck of the railroad trestle

bridge, the abutment having been eroded by the 19 February 1911 flood of the Pecatonica River, causing

the structure to collapse. The locomotive brakeman swam to a tree and was forced to wait there for

half an hour before being rescued. The big white house in the background is not the Nathaniel

Martin residence. It is the home of James and Rosie Van Matre and family, who in the early 20th Century

had the property immediately to the west of the Martin parcel. (Minta, Ava, and Christie Van Matre,

shown in the teens-on-the-river-ice photo above, were three of James and Rosie’s kids.) The building

at the far left, in the water, is the Martin School. Locals considered the collapse quite a dramatic

event. The bridge had been built in LaSalle, IL in 1868 and was moved to Martintown decades into its

lifetime, and was not considered likely to give way as it did. It led to the photographer or his

employer publishing for sale several different vantages of the scene. This one is number four in the

sequence.

Elwood Bucher founded the electrical plant in the autumn of 1908 after winning the contract to supply

Winslow with power for its street lights. The business became increasingly valuable as

electricity became more widely used in the 1910s. A consortium based in Lena, IL made Elwood an offer and

he sold the business (even while, for the time being, hanging on to ownership of the grist mill and

sawmill). In 1922, the consortium sold out to Wisconsin Power & Light of Monroe, WI. They replaced the

aging dam that year, installing a concrete one a full six feet in height, which provided enough

river flow to greatly improve the efficiency of the dynamo. In about 1930, the company replaced the aging

equipment with an up-to-date dynamo and built the brick structure you see here to house it. This

photograph was taken not long after the new building was completed. This was

scanned from the 1931 edition of the Win-Nel, the yearbook of Winslow High School. The book was

in print by the summer of 1931, so the photograph, which shows the trees either losing their leaves or

just beginning to fill in with foliage, could only have been taken in the autumn of 1930 or the spring

of 1931. The plant remained a key part of Martintown’s economic vitality in later years. However, the

river silted up behind the dam, leading to complaints of flooding by local farmers. At one time the

site accounted for a small but meaningful fraction of the electricity generated in Green County.

By the 1950s, given the reduced river flow, the megawattage was less significant and Wisconsin Power &

Light agreed to the removal of the dam.

This is Nathaniel and Hannah’s house as it looked in 1960. It still strongly resembles the version seen

in the views from the late 1800s. In recent years trees have filled in thickly on the hillside behind the

residence. The structure underwent major renovations in 2005.

This is another photograph taken in 1960 during the Eastertime visit by Bert Warner and his family

to his old hometown. From this angle the absence of the larger two mill buildings is obvious. Only the

smallest of the original three buildings remains, the one that used to be in the middle, oriented

perpendicular to the river (whereas the two larger buildings had been oriented parallel to the river).

It is visibly delapidated. It would not last much longer. Its final owner was Marilyn Miskimon. The dam

is absent as well, having been torn out a few years earlier. The brick building erected by Wisconsin

Power and Light was left standing when that demolition occurred, and is prominently visible here. It

remains even today (current 2012). To those of us able to view the collection of images on this webpage,

it is easy to see the

similarity between 1890 and 1960. For Bert Warner, who was in his mid-seventies in 1960 and had only

visited Martintown occasionally after 1906, it was surely the differences that impressed him.

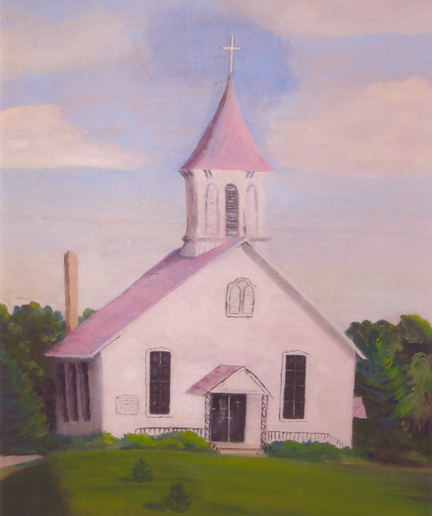

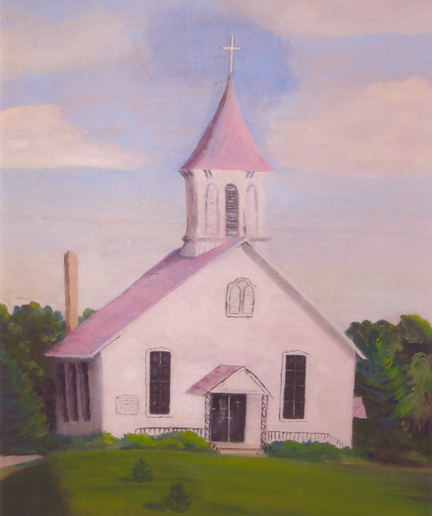

Photograph taken 2 November 2005 by Dave Smeds. This church was “built” by Nathaniel in 1879.

That is to say, he requisitioned the structure, provided the land, and no doubt paid the major portion

of the materials and labor cost. During Nathaniel’s lifetime it was a United Brethren house of worship,

served by a travelling pastor. In the early decades of the 20th Century the place fell into disrepair

and was abandoned in 1937. In 1946, a coalition of three denominations spearheaded by Reverend Roy Berg

came together to kick out the resident pigeons and proceed to restore and re-open the landmark for

regular use -- an effort that required the acquisition of replacement stained-glass windows from another

vintage church because vandals had thrown rocks through the original ones. As can be seen in this view,

the structure was in excellent condition in 2005, by which time it had become known as Martintown

Community Church. In the mid-2010s, a major congregational effort resulted in the addition of a social

hall extending to the east. It nearly doubled the size of the church and gave its footprint an L shape

rather than a plain rectangular one. Care was taken to preserve the old portion as much as possible.

The refurbishment was spearheaded by Kevin Cernek, who has served as pastor beginning in 1994. His wife

Cindy is a great great great granddaughter of Nathaniel and Hannah.

In 1954, a run of these souvenir plates were created to commemorate the 75th anniversary of the

founding of the church. The copper-gold highlights you see here are the result of camera flash, and

are not part of the plate design. The plate used for this photograph once belonged to Bert Warner,

who participated in the 75th anniversary celebration. Bert was also on hand in 1979 for the 100th

anniversary, coming out all the way from his home in California at age ninety-five.

This painting of the Martintown church was created by Leah Merle Hastings Schumacher, great-granddaughter

of Nathaniel and Hannah. Leah was one of the rare great-grandchildren to remain local to Martintown into the

latter part of the 20th Century (and in her case, even into the 21st Century). She attended many services

and other events within its walls over the course of her lifetime. The 1931 photograph of the Martintown dam

shown higher up was scanned from her copy of the 1931 Win-Nel.

The Martintown band in the early 1890s. Nathaniel’s grandson Charles Elias Warner is the

seated man at the very center of the group. Taken by W.T. Nash, Photographer, Lena, Stephenson

County, IL.

As the Great Depression settled upon America, Martintown felt the effects. Normally a quiet and

secure place to live, a robbery of the community’s general store/post office -- operated at that

time by Nathaniel’s great-grandson Leland Francis “Hap” Hastings and his wife Hulda -- occurred 27

December 1929. The photos above chronicle the reaction of the local folk: 1) Here is the storefront

window the thief broke in order to get in. After the crime was discovered, 2) the bloodhounds were

brought in, 3) the whole town turned out to help search for the fugitive, 4) a car blocked off an

escape down Bridge Street, and 5) the citizens began combing the area on foot. This series of images

was scanned from snapshots that belong to Hap’s son Jerry Hastings, who was six years old at the

time the event occurred.

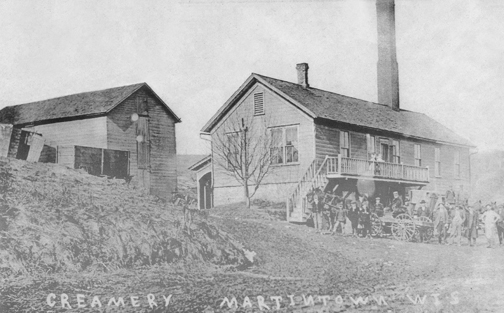

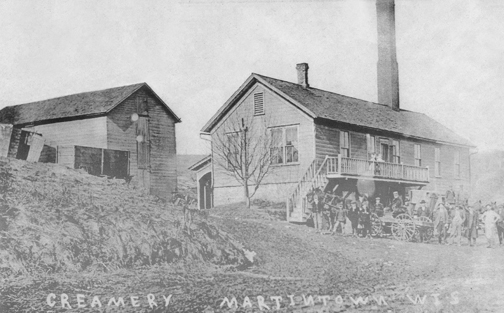

This was the Martintown creamery and cheese factory. For many years in the 1890s and early part of

the 20th Century it was managed, and later owned-and-managed, by butter maker Thomas Devlin, who was a

brother-in-law of Elwood Bucher. The cheese factory was the

final wholly-new commercial building added to the village. While other money-making ventures were

initiated later, their founders all chose to retrofit existing structures, as when the mills became

the home of Elwood Bucher’s electrical generation plant. The cheese factory enjoyed a long run, but like

all of Martintown’s businesses, it eventually ceased operation. The building still stands, but became a

residence decades ago. Like many of the images above, this one was made into a postcard. Unfortunately

the original postcard was not available for scanning and this copy of a copy of a copy has lost quite a

bit of image quality. Another fairly clear view of the creamery is in the final “robbery” shot shown

just above. The creamery’s tall chimney was its distinctive feature.

In the late 1800s, farmers more and more began putting their oxen and plow horses out to pasture and

resorted instead to mechanized devices for harvesting and cultivation. Until internal combustion engines

were perfected in the early 1900s, steam engines were the fashion. This image was scanned from an original

photograph that belonged to Nathaniel’s great-granddaughter Selma Warner Mead and eventually ended up in

the mementoes of her uncle, Bert Warner. The scene, photographed by Martintown depot stationmaster E.B.

Lund (a good friend of the Warner clan), preserves a visual record of the “Warner Brothers” steam tractor

threshing rig at work on a Cadiz Township farm some time in the early 1900s. The most likely precise date

is the harvest season of the year 1904. This 16-horsepower Advance engine rig had originally been acquired

by John Warner, husband of Nellie Martin, in 1892 (or in early 1893), in tandem with his older sons, John

Martin Warner, then age 22, and Charles Elias Warner, then age 20. The two young men had then proceeded

each year to lease out the rig and their services to farmers in northern Stephenson County, IL and

southern Green County, WI. Newspaper articles confirm they were still doing so in 1905, though by then,

John M. Warner was a Martintown shopkeeper and his role with the threshing rig had been filled by younger

brother Cullen Clifford Warner. (Cullen, born in 1882, had only been ten years old when the rig was

purchased, and had been too young to be part of the original Warner Brothers team.) In this photo, Cullen

is standing on the far left. His father John is immediately to his right, leaning on the tractor, arms

folded. You will note the water wagon on the right, waiting behind its team of horses. Less easy to make

out in this low-resolution jpg is the huge stack of hay behind the water wagon. Seven or eight men are

pitchforking hay into the hopper of the threshing rig. The tractor is supplying power to the threshing rig

via the long conveyer belt that runs horizontally across the middle of the scene. One has to wonder if

everyone had cotton stuffed in their ears. As this sentence from the 18 August 1903 edition of the

Freeport Journal-Standard confirms, the apparatus was extremely loud: “The Warner Bros. are out

with their threshing machine; their double whistle can

be heard for miles around.” The rig was regularly mentioned in the section of the newspaper devoted

to bits of news about Martintown and Cadiz Township. Another example is from the 6 October 1905 edition:

“The Warner threshing outfit passed through town Tuesday afternoon enroute for J. Dittmers. They said

that was their last job of threshing, and now will hull clover for the rest of the season which will only

last a week or so.”

To return to the Martin/Strader Family main page, click here.

The life story of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader is, in

some ways, the story of the place they lived from 1850 onward -- the village of Martin, later to

be called Martintown, which Nathaniel founded. Nathaniel owned and operated the sawmill and grist

mill that were the economic heart of the community. He was the major landowner. He established the

community church. He left his bones in the cemetery that overlooked the mills, bridge, and main

street. He was Martintown. To honor him and his family properly, one must give due attention

to the spot where he and

Hannah resided for the majority of their lives. This page collects some pictures of Martintown

and vicinity, and covers some of the general history of the place above and beyond what you will

find interspersed within the biographies of the family members.

The life story of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader is, in

some ways, the story of the place they lived from 1850 onward -- the village of Martin, later to

be called Martintown, which Nathaniel founded. Nathaniel owned and operated the sawmill and grist

mill that were the economic heart of the community. He was the major landowner. He established the

community church. He left his bones in the cemetery that overlooked the mills, bridge, and main

street. He was Martintown. To honor him and his family properly, one must give due attention

to the spot where he and

Hannah resided for the majority of their lives. This page collects some pictures of Martintown

and vicinity, and covers some of the general history of the place above and beyond what you will

find interspersed within the biographies of the family members.

All of the surviving gravemarkers -- believed to be all

that ever existed -- are devoted to close

Martin family members. The group includes Nathaniel and Hannah themselves, nine of their children, three

of their grandchildren, Hannah’s nephew Elias Frame, and Nathaniel’s father James Martin. Most of these

gravemarkers can be seen in this view. The large stone in the foreground is that of Nathaniel and Hannah.

Their names appear on the front of the stone. Inscribed on the sides and reverse are the names of children

William, Charles, Christie Belle, James Franklin, and Hannah, all of whom died very young. (The other child

who died young was Alice Adelia Martin, who was buried elsewhere, location unknown. She died before the

Martin cemetery had been established.) The other large marker is that of Mary Lincoln “Tinty” Martin Bucher,

its size reflecting the intent that her husband Elwood Bucher would be buried alongside her one day. But in

the end, the place where his name and stats would have been etched was left empty, because he was buried in

Rock Lily Cemetery in Winslow along with other Bucher family members, having moved Tinty’s body and casket

to that locale some time in the 1920s. The medium-sized marker is that of Jennie Edith Martin Hodge. Leaning

against it is the headstone of Abraham Lincoln “Linky” Martin. The latter stone’s original placement is now

guesswork. The same applies to the headstone of James Martin, shown here leaning against a tree. In the

distance, at the far edge of the cemetery, you can make out the bluish marker of Elias Frame (close-up

view shown at right), whose burial here was a matter of happenstance. Elias had moved away from the area

approximately thirty years before his death in 1901. In the early 1890s he had settled in Tulare County,

CA. He died unexpectedly during a visit to see his relatives back in Green County and the decision was made

to bury him in the Martin graveyard rather than ship his body all the way to California. Not visible in

this view are the markers of Horatio Woodman Martin, Fay Horatio Martin, Ida Ellen Warner, and Minnie Edna

Brown. Fay was

the very last person buried on-site. Once Nathaniel and Horatio passed away in quick succession in 1905

and 1906, the practice of regular burials here ceased. Naturally Hannah was laid to rest with her husband

when she died in 1919, but she was the last until her grandson Fay made arrangements to be interred among

his kinfolk. Fay left instructions that he be put in the ground dressed in his overalls, and his wish was

obeyed. Fay died in 1965, so his burial represented the first time the cemetery had welcomed a new occupant

in forty-six years.

All of the surviving gravemarkers -- believed to be all

that ever existed -- are devoted to close

Martin family members. The group includes Nathaniel and Hannah themselves, nine of their children, three

of their grandchildren, Hannah’s nephew Elias Frame, and Nathaniel’s father James Martin. Most of these

gravemarkers can be seen in this view. The large stone in the foreground is that of Nathaniel and Hannah.

Their names appear on the front of the stone. Inscribed on the sides and reverse are the names of children

William, Charles, Christie Belle, James Franklin, and Hannah, all of whom died very young. (The other child

who died young was Alice Adelia Martin, who was buried elsewhere, location unknown. She died before the

Martin cemetery had been established.) The other large marker is that of Mary Lincoln “Tinty” Martin Bucher,

its size reflecting the intent that her husband Elwood Bucher would be buried alongside her one day. But in

the end, the place where his name and stats would have been etched was left empty, because he was buried in

Rock Lily Cemetery in Winslow along with other Bucher family members, having moved Tinty’s body and casket

to that locale some time in the 1920s. The medium-sized marker is that of Jennie Edith Martin Hodge. Leaning

against it is the headstone of Abraham Lincoln “Linky” Martin. The latter stone’s original placement is now

guesswork. The same applies to the headstone of James Martin, shown here leaning against a tree. In the

distance, at the far edge of the cemetery, you can make out the bluish marker of Elias Frame (close-up

view shown at right), whose burial here was a matter of happenstance. Elias had moved away from the area

approximately thirty years before his death in 1901. In the early 1890s he had settled in Tulare County,

CA. He died unexpectedly during a visit to see his relatives back in Green County and the decision was made

to bury him in the Martin graveyard rather than ship his body all the way to California. Not visible in

this view are the markers of Horatio Woodman Martin, Fay Horatio Martin, Ida Ellen Warner, and Minnie Edna

Brown. Fay was

the very last person buried on-site. Once Nathaniel and Horatio passed away in quick succession in 1905

and 1906, the practice of regular burials here ceased. Naturally Hannah was laid to rest with her husband

when she died in 1919, but she was the last until her grandson Fay made arrangements to be interred among

his kinfolk. Fay left instructions that he be put in the ground dressed in his overalls, and his wish was

obeyed. Fay died in 1965, so his burial represented the first time the cemetery had welcomed a new occupant

in forty-six years.