The Ancestry of Nathaniel Martin

Nathaniel Martin’s parents were James Martin, who was

born in the late 1770s in Virginia and died 9 October 1856 in Martintown, Green County, WI, and

Rebecca Pearcy, born circa 1790 in Bedford County, VA, who survived until at least 1860. That

Nathaniel had these particular parents is not in doubt. But as one goes back in time, there are some

major blanks in his family tree. Certainly it is fair to say that we know less about Nathaniel Martin’s

forebears than we do about those of his wife, Hannah Strader.

Nathaniel Martin’s parents were James Martin, who was

born in the late 1770s in Virginia and died 9 October 1856 in Martintown, Green County, WI, and

Rebecca Pearcy, born circa 1790 in Bedford County, VA, who survived until at least 1860. That

Nathaniel had these particular parents is not in doubt. But as one goes back in time, there are some

major blanks in his family tree. Certainly it is fair to say that we know less about Nathaniel Martin’s

forebears than we do about those of his wife, Hannah Strader.

The lack of available material is especially profound regarding the origins of Nathaniel’s

father, James Martin. What we do have is not reliable. For example, Nathaniel’s biography in

the 1901 volume, Commemorative Biographical Record of the Counties of Rock, Green, Grant,

Iowa, and Lafayette, Wisconsin, states that James’s father was born in Ireland. We can’t

trust that. The same source also states that Nathaniel’s maternal grandfather James Pearcy was

born in England. This is known to be untrue. James Pearcy was native to the Colonies. The immigrant

was his father -- Nathaniel’s great grandfather -- John Pearcy. The tendency in old-fashioned

biographies to get the timing of family emigration from Europe wrong is notorious. There is ample

reason to suspect that this factor was in play in the 1901 sketch in regard to the Irish side of the

family. James Martin’s parents were probably either native Virginians or came as children from

Pennsylvania. The latter possibility looms large because James was likely to have been a native of

Franklin County, VA. That was a county whose original population of white settlers had come as a

result of a major migration in the mid-1700s of Irish, Scots, and German families from Pennsylvania

down the Carolina Road (also know as the Great Indian Warrior Path) to the piedmont just east of the

Blue Ridge Mountains. There were Martins among those families, including one James A. Martin noted on

the list of original settlers, who was of the right generation to be a great-grandfather of Nathaniel.

Unfortunately the surname Martin is so common it turns up in lists of original settlers of just about

every sub-region of the thirteen colonies. Until better clues narrow the possibilities, it is impossible

to be sure just

what family James Martin (father of Nathaniel) sprang from. The doubt is great enough that we can’t totally

discount the possibility that James’s parents did personally hail from Ireland. All that can be said

with any degree of confidence is that James appears to have been a resident of Franklin County in 1809

when the James Pearcy family -- including Rebecca, who was then about nineteen years old -- moved there

from neighboring Bedford County. (A larger version of Bedford County had spawned Franklin County in 1785.

The Pearcy clan lived in the part that retained the Bedford designation.) One way or another, he

was in Franklin County when he and Rebecca married one another on the 18th of October, 1811. (Old

family notes say the marriage date was the ninth. This is probably an error, though there is the possibility

it might be the date the marriage bond -- the 18th Century equivalent of a marriage license -- was signed.)

There is one shred that might indicate a means to uncover James Martin’s ancestry. His eldest son was

named Redmond Martin. This is a very unusual first name and probably indicates Redmond was the

maiden last name of James’s mother. A man named Lawrence Redmond acquired a land patent for four hundred

acres in Louisa County, VA 12 April 1753. A man named Ignatius Redmond took his oath of allegiance to the

Colonies in 1777 in Pittsylvania County, VA. It is worth asking if either or both of these men might

have been relatives.

More intriguing are traces left in Quaker meeting record books from 1760s Philadelphia. A couple named

Joseph and Sidney Redman were active in the Friends community there, and the references in the registers

include notations of their deaths and burials, Sidney in 1765, and Joseph in 1768. The spouses were the

perfect age to have produced a daughter who might have gone on to marry a Mr. Martin and give birth to

James Martin in the late 1770s. Joseph Redman’s last name would have been a source for Redmond Martin’s

first name -- which is sometimes rendered as Redman Martin in 19th Century sources -- while James and

Rebecca’s eldest daughter Sydney Martin, aka Sidney, might well have been named for her grandmother.

Quaker heritage would also help explain why James and Rebecca’s kids grew up with an intolerance of

slavery despite their southern origins. By the latter decades of the 18th Century, the Quaker church had

declared slavery to be morally wrong, and even in the South, members of the faith adhered to that position.

While the heritage of James Martin remains frustratingly obscured, we can be consoled that the genealogical

background of Rebecca Pearcy extends much further into the light of day. This is particularly true

concerning her immediate male ancestors, namely her father James Pearcy and her grandfathers John Pearcy

and Paulser Smelser. These men lived long enough -- and documentation about them is plentiful enough -- to

create reasonably accurate biographical sketches of them. Furthermore, with those three figures as

“research anchors,” it is possible to be sure of the identities of several more of Rebecca’s ancestors,

including some of the females.

John Pearcy

John Pearcy of England settled in Bedford County, VA in the late 1760s and lived out the rest of his

long life there, much or all of it on his substantial holdings along Goose Creek. In the 1810s, as an

elderly widower, John bequeathed and/or sold the estate to his youngest sons Edmond, Henry, and

Nicholas. Edmond was by that point a resident of Botetourt County and consequently sold his share to

Henry and Nicholas. The latter duo each ended up with about three hundred acres apiece, Nicholas and

his wife and children taking possession of the original home. After Nicholas’s death in 1854 the

property soon passed out of family hands, but thanks to the unbroken chain of deed transfers preserved

in county records, it is easy to show that the modern-day address of the original

home is 1704 Quarterwood Road, Montvale, VA. It is still rural property. The village of Montvale, population

approximately 700, is about a mile to the northwest. Montvale is about ten miles west of the town of

Bedford and about ten miles northeast of the city of Roanoke. The home at 1704 Quarterwood Road and its

outbuildings even now (or at least as of the early 1980s, when John’s elderly Florida-based great great

granddaughter Frankie Pearcy McAlpine paid a visit) contain parts of the historical structure such as the

log-lumber inner frame of the main house and the brick foundations of the outbuildings, which were probably

in John’s day the kitchen and the spring house. (A spring house was an 18th-Century version of a

refrigerator. It was a root-cellar-sized structure designed so that cold springwater ran through it. Sealed

containers were placed in the water, which kept the contents nicely chilled.)

(Shown at right and slightly below left are two views of

the house and outbuildings of 1704 Quarterwood Road as they appeared in 1999. These photographs were taken

by descendant Jo Ann O’Brien during a cross-country family history research trip.)

(Shown at right and slightly below left are two views of

the house and outbuildings of 1704 Quarterwood Road as they appeared in 1999. These photographs were taken

by descendant Jo Ann O’Brien during a cross-country family history research trip.)

The well-preserved nature of records in Bedford County is a blessing not to be taken for granted. The

city of Lynchburg, located at the eastern boundary of Bedford County, was the only major urban center

in Virginia that did not fall to the Union during the Civil War. In various other parts of the state,

county courthouses went up in flames and it is not possible now to look up pre-1865 vital-stats records.

By contrast, Bedford County enjoys a much better situation. The Bedford County Museum has so much

documentation regarding the Pearcy family that the staff maintains a designated surname file. In addition

to this bit of fortune, descendants can also be thankful that the original family was well-educated.

Various children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren of John rose to positions of prominence as

lawyers, doctors, teachers, holders of government office, and major property owners. They left

writings -- including correspondence and Bible family-group entries -- that preserved a substantial

amount of genealogical lore. One great-grandson, Joel Nathaniel Pearcy (1860-1931), an attorney based in

Salem, OR, wrote a family history in the 1910s that included the names and birthdates of the original

family. One of Joel’s uncles, George Pearcy (1813-1871), was a Southern Baptist missionary to China from

1846 to 1854. The Mt. Zion Baptist Church members back in Bedford County thought so well of him that over

the years a number of profiles have appeared, drawing upon the trove of writings about him and by

him -- including letters he wrote while in China -- preserved within church archives. These profiles

describe George’s roots, including his descent from his grandfather John Pearcy.

What we don’t know with absolute certainty is John’s own genealogical origins. The John Pearcy who settled

in Bedford County was definitely from England and appears to have been born in the late 1730s. Early family

genealogical writings specify Devon, England, and all of this points to him being a certain John Pearcy

born 10 April 1737 in the village of Uffculme in the Blackdown Hills. This would make him a son of yet

another John Pearcy, one who was also a native of Uffculme, born about 1710. The elder John married

Elizabeth Webber 17 April 1736 in Uffculme, the timing indicating John was the firstborn child of their

union. These parents apparently stayed in England to the end of their days. They played only a brief role

in the life of “our” John, because according to family legend, John ran off to sea when he was a boy,

perhaps even as young as ten or eleven, and made his fortune captaining a ship for ten years.

Anyone with a healthy dose of skepticism who comes across an adventure story like that knows the truth has

been stretched. And indeed it must have been. John settled

down in Virginia as a married man just after turning twenty-one years old, assuming the 1737 birth year is

correct. He didn’t have time to have been a ship captain for ten years unless his crew accepted him as their

leader when he was a child. What kind of sailors would do that? However, once the mud is cleaned from the

eyeglasses, this quite reasonable picture emerges:

In the mid-1700s, the wool raised in the Blackdown Hills was

prized by Dutch textile manufacturers. The Dutch factories generated clothing not only for Europeans, but

for the many colonists headed to Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina on King George’s ships. The

Pearcy family

appears to have been well-to-do, and to be well-to-do in Uffculme in the mid-1700s is essentially the same

as saying the clan was engaged in shipping wool to the Netherlands. Young John, as a firstborn son and heir,

would have been encouraged to gain direct expertise in the family trade, and probably spent an apprentice

period going back and forth across the English Channel, either with his father or -- more likely -- with

a captain who worked for Uffculme-area employers including the Pearcy clan. Young John, as a person of good

family, would have advanced rapidly in authority until by his late teens, he might well have been been put

in charge of a vessel and/or its cargo. It is reasonable to assume he subsequently became involved

in more ambitious enterprises that resulted in him crossing the Atlantic. Once in Virginia, he decided to

stay. Perhaps his father was dead by then. Perhaps he wanted to be out from under the thumb of his father.

Maybe he just liked the idea of forging a life for himself in a new place rich with opportunity. He had

enough of a nest egg by the age of twenty-one that he could marry and start a family -- no small thing in

an era when men of the upper class usually required quite a bit more time than that before they were

established enough to settle down.

In the mid-1700s, the wool raised in the Blackdown Hills was

prized by Dutch textile manufacturers. The Dutch factories generated clothing not only for Europeans, but

for the many colonists headed to Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina on King George’s ships. The

Pearcy family

appears to have been well-to-do, and to be well-to-do in Uffculme in the mid-1700s is essentially the same

as saying the clan was engaged in shipping wool to the Netherlands. Young John, as a firstborn son and heir,

would have been encouraged to gain direct expertise in the family trade, and probably spent an apprentice

period going back and forth across the English Channel, either with his father or -- more likely -- with

a captain who worked for Uffculme-area employers including the Pearcy clan. Young John, as a person of good

family, would have advanced rapidly in authority until by his late teens, he might well have been been put

in charge of a vessel and/or its cargo. It is reasonable to assume he subsequently became involved

in more ambitious enterprises that resulted in him crossing the Atlantic. Once in Virginia, he decided to

stay. Perhaps his father was dead by then. Perhaps he wanted to be out from under the thumb of his father.

Maybe he just liked the idea of forging a life for himself in a new place rich with opportunity. He had

enough of a nest egg by the age of twenty-one that he could marry and start a family -- no small thing in

an era when men of the upper class usually required quite a bit more time than that before they were

established enough to settle down.

John did not begin the American chapter of his life in Bedford County. His son James (father of Rebecca

Pearcy Martin) testified in 1832 that he had been born in 1762 in Buckingham County, VA, and remained there

until the age of six, i.e. until about 1768, whereupon the family relocated to Bedford County. It stands

to reason that James’s two older siblings might also have been born in Buckingham County, which would put

John’s arrival there in the second half of the 1750s. But Buckingham County, like Bedford County, is in the

heart of Virginia, well inland and therefore not where John got off the boat. Where he landed, and how long

he stayed there, is unknown. This makes the locale of his marriage a guess as well. Happily,

we do have a solid date for the wedding. This comes not from public sources, but from lore maintained by

descendants, originally preserved in family Bibles. John’s bride was Anna Margaret Spencer. He married

her 29 December 1758.

Anna Margaret Spencer was a Virginian, born about 1738. Chances are she came from a more easterly part

of Virginia than Buckingham County, but precisely where is unknown. She was a daughter of Thomas Spencer,

about whom nothing further is available. However, just having Thomas’s name is something to be thankful for,

as that makes him one of the three great-grandparents of Rebecca Pearcy who can be identified. How we

have this name is currently a mystery. Probably some family genealogist found the name mentioned on the

1758 marriage bond during research conducted before the Civil War, when the document still existed in

Buckingham County archives. Marriage bonds often included the name of the father of the bride.

The family of John Pearcy and Margaret Spencer grew steadily from 1759 to 1779. It included ten known

children, the first four or five born in Buckingham County, the rest born after the relocation to Bedford

County. The very first was William, born just three months into the marriage (assuming

his birthdate of 30 March 1759 is correctly reported). The full list of ten is William, Mary, James, Sarah

Jane, John (III), Charles, Isham, Edmond Talbot, Henry, and Nicholas. (A prominent Pearcy family researcher

adds Nancy, born about 1781, but this is not conclusive. Contrary evidence indicates Nancy was either a

granddaughter or a daughter-in-law of John and Margaret.)

The land John and Margaret owned along Goose Creek was prime acreage, a mark of how prosperous the

family was. The piece acquired in the late 1760s was only the beginning. New tracts were added over the

course of thirty years until the estate consisted of more than a thousand acres. The Cherokee and other

native tribes had used this swath of land on a regular basis for centuries, recognizing its plentiful

virtues, which included fertile soil, good water, fishing and hunting opportunities, and superb view of

the Blue Ridge Mountains.  (Shown at right, a modern-day

view of Goose Creek Valley.) The colonists recognized another quality -- Goose Creek ran fast, which

was perfect for waterwheel power. There were more mills along the stream than in any other part of

Bedford County, even back when Bedford County’s boundaries encompassed areas that are now part of

Campbell County, Franklin County, Botetourt County, and the City of Lynchburg. There is nothing said in

county histories or in family notes that confirms whether John owned a mill, but it would stand to reason

that he may have. Here we may have an explanation why his great-grandson Nathaniel Martin was intrigued

by the idea of installing a woolen mill at Martintown.

(Shown at right, a modern-day

view of Goose Creek Valley.) The colonists recognized another quality -- Goose Creek ran fast, which

was perfect for waterwheel power. There were more mills along the stream than in any other part of

Bedford County, even back when Bedford County’s boundaries encompassed areas that are now part of

Campbell County, Franklin County, Botetourt County, and the City of Lynchburg. There is nothing said in

county histories or in family notes that confirms whether John owned a mill, but it would stand to reason

that he may have. Here we may have an explanation why his great-grandson Nathaniel Martin was intrigued

by the idea of installing a woolen mill at Martintown.

Having so much land naturally meant that John owned slaves. Being slaveowners, or living among neighbors

who owned slaves, was the rule, and this would remain the case for multiple members of the next two generations

of the family. For example, grandson George Pearcy, the missionary, spent his long period of convalescence

after returning from China dwelling on the plantation of his father-in-law Samuel Miller in Pittsylvania

County, VA. In John’s time, slave-ownership was the accepted norm. What stands out is the choice of various

children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren to move to free states such as Indiana, Wisconsin, and

Oregon. The piedmont and hills were less given-over than other parts of the South to the plantation lifestyle

and all it entailed, and attitudes of individual family members were varied -- an interesting subject,

leaving a person wishing a full archive of letters survived to shed light on the differences of philosophy

within the clan.

John was turning forty as the Revolutionary War kicked into gear. There is no evidence he took up arms.

As a prosperous man, and as a native of England, he might well have possessed Tory sentiments. This was not

the prevailing view in the area and if he did have these opinions, he probably kept them to himself. His

two oldest boys, William and James, came of age in time to fight in the 1780s in the latter part of the

conflict. Both appear on the list of Bedford County men who fought for the revolution. Had they been

older, given their social position, they might well have been officers. As it was, both only held the

rank of private. (For more about James’s service, see his section below.)

All of John and Margaret’s children remained in Bedford County well into their adulthoods. This is worth

noting, as it hints strongly that the couple were good parents whose kids wanted to stick around -- a

remarkable display of a strong bond in an era when the frontier was steadily expanding westward and new

opportunities were beckoning. Some of the kids, like Charles, Henry, and Nicholas, would remain in Bedford

County until their deaths. Others -- and eventually, nearly all of the later generations -- did yield to

the lure of new lands, but John and Margaret were old when the process began and did not have to be

personally confronted with the exodus in its full scope. The first to leave appears to have been Sarah

Jane with her husband Henry Miller, who departed about 1800, but even Sarah and Henry do not appear to

have left out of unhappiness with Bedford County and the company of all those Pearcy family members, but

went to manage property John had acquired in

Kentucky. This scenario may also have been the case with James, who left in 1809 for Franklin County, VA,

and then eight years later went on to Wayne County, KY.

Margaret died first, perhaps as early as 1807, but surely by 1811. The precise dates of death for the

couple were not preserved in

the family genealogies and must be guessed at by the deeds being transacted in Bedford County. In 1811,

John transferred Goose Creek parcels to sons Edmond and Henry in a manner that strongly infers Margaret

was deceased and John no longer needed to hold on to his entire estate so as to support Margaret in her

widowhood. John himself appears to have survived until 1816 to personally transfer more Goose Creek land

to son Nicholas. Then in 1819, Nicholas and Henry bought Edmond's portion, splitting it more-or-less

equally between them. The language used in the 1819 deeds describe the land as part of John’s estate -- as

in, John was deceased.

Many Pearcy genealogies include quite different death dates, claiming that John died 28 July 1834 and was

survived by Margaret, who survived a few more years to die just shy of her one hundredth birthday. This is

an error on the part of Joel N. Pearcy in his 1910s genealogical essay. Joel had obtained a copy of a

letter written 25 July 1914 by an eighty-seven-year-old native of Bedford County, Rowland Buford, to Annie

Owen, a granddaughter of Charles Pearcy, son of John and Margaret. Rowland Buford’s grandfather and several

of his brothers were among the early settlers of Bedford County. Rowland himself had grown up going to

school with various Pearcy boys, including Joel’s father Nathan, and for part of that time, the class

was taught by Nathan’s eldest brother, Abner Pearcy (son of Nicholas). Rowland Buford forwarded to Annie

Owen a copy of the last will and testament of John Pearcy, a document filed with the county clerk 8

February 1834 and probated 28 July 1834. Buford goes on to say that John’s widow Nancy inherited the

estate, and upon her death it went to John’s brother Nicholas, presumably because John had no issue. (He

had not married Nancy until he was almost sixty years old.) These are references to John Pearcy born in

1768, the son of John Pearcy and Anna Margaret Spencer, and to John’s widow, Nancy Agnew Pearcy, daughter

of William Agnew. Yet Joel N. Pearcy for some reason concluded that Buford was wrong and the will was that

of the elder John Pearcy. Why he did so is a mystery. Perhaps he thought that the younger John Pearcy was

long gone to Kentucky -- perhaps mistaking him for James. Joel N. Pearcy was a native of Oregon and may

never have visited Bedford County, VA in his entire life. Rowland Buford, on the other hand, knew exactly

what he was talking about. Unfortunately, Joel’s essay became one of the key sources of information about

the Pearcy clan. For a hundred years, his error has propagated, leaving us with all too many genealogies

that use 28 July 1834 as the date of “the” John’s death -- a date that isn’t even a precise death date of

any family member, just the date when John the younger’s will entered probate.

The farm at 1704 Quarterwood Road shows signs of a family cemetery on a rise near the house. There are no

headstones, but chances are good this was the place where John and Margaret were laid to rest.

Paulser Smelser

Paulser Smelser, the other well-known great-grandfather of Nathaniel Martin, was another settler of

Bedford County, VA. He and his family owned and lived on Goose Creek property quite near the Pearcy

holdings. Both families appear to have made this area their main base of operations at about the same

time, i.e. the late 1760s. However, unlike John Pearcy, Paulser Smelser arrived having spent the preceding

years even farther to the west. An ample amount of documentation -- deeds, tax records, court filings,

etc. -- shows that Paulser was active in what is now Montgomery County, VA by the beginning of 1754. In

mid-January of that year, Paulser agreed to a one-year lease of 440 acres of the James Patton tract

along Crab Creek, a stream that runs into New River just a bit north of the modern-day town of Radford.

The lease apparently came with an option to buy, which Paulser exercised within a few years. The 440 acres

remained in Smelser hands until sold by Paulser’s eldest son John Smelser in 1787.

Montgomery County is fully within the Appalachian Mountains and

the place was very much the frontier at the time of Paulser’s arrival. It was at that point part of

Augusta County, but Augusta wasn’t so much a county as an “off the edges of the map” sort of zone. When

formed from Orange County in 1738, Augusta County consisted of the entire swath that the colony of

Virginia imagined to be under its sovereignty but which had yet to come under the active supervision

of European-Americans. It was all lumped into the designation Augusta County because bureaucratically

speaking it wasn’t yet worth being carved up into smaller jurisdictions. The boundaries included all

of what is now Kentucky, most of what is now West Virginia, and much of what is now modern Virginia

from the piedmont to the Kentucky border. Even by 1754, only the eastern fringe of this expanse had

been settled by whites. Native tribes, aided by and encouraged to violence by the French, were lashing

out against encroachment. One relevant example is

the incredible tale of Mary Draper Ingles. In July, 1755, Shawnee raiders killed four New River-area

settlers and captured five others, including twenty-three-year-old Mary and her young children. Mary

escaped several weeks later and even though she had been taken hundreds of miles west to a spot along

the Ohio River near present-day Cincinnati, managed to make her way back to her husband and neighbors

along New River to tell the tale. (She and her husband lived in the cabin shown at left, a structure

built after her return.) Her story was preserved in material written by her son John Ingles, published

in 1824, and her grandson John Peter Hale, published in 1886. The story became the basis of the

bestselling 1981 novel Follow the River by Alexander Thom. Earlier it was the basis for a

long-running historical play (often staged in Radford) “The Long Way Home” by Earl Hobson Smith.

These resulted in the ABC-network made-for-tv movie Follow the River in 1995 and the film The

Captives in 2004. Mary and the others were taken from a spot described as being part of the James

Patton tract. James Patton himself was one of the four killed in the raid, shot as he tried to fend

off a set of attackers with his broadsword. The tract was over a thousand acres in size, but it could

well be that on that infamous day, the Shawnee traversed Paulser’s land on their way

to the Patton and Ingles cabins. In a way, Paulser could be described as an adventurer simply by

choosing to reside in this unsecured territory.

Montgomery County is fully within the Appalachian Mountains and

the place was very much the frontier at the time of Paulser’s arrival. It was at that point part of

Augusta County, but Augusta wasn’t so much a county as an “off the edges of the map” sort of zone. When

formed from Orange County in 1738, Augusta County consisted of the entire swath that the colony of

Virginia imagined to be under its sovereignty but which had yet to come under the active supervision

of European-Americans. It was all lumped into the designation Augusta County because bureaucratically

speaking it wasn’t yet worth being carved up into smaller jurisdictions. The boundaries included all

of what is now Kentucky, most of what is now West Virginia, and much of what is now modern Virginia

from the piedmont to the Kentucky border. Even by 1754, only the eastern fringe of this expanse had

been settled by whites. Native tribes, aided by and encouraged to violence by the French, were lashing

out against encroachment. One relevant example is

the incredible tale of Mary Draper Ingles. In July, 1755, Shawnee raiders killed four New River-area

settlers and captured five others, including twenty-three-year-old Mary and her young children. Mary

escaped several weeks later and even though she had been taken hundreds of miles west to a spot along

the Ohio River near present-day Cincinnati, managed to make her way back to her husband and neighbors

along New River to tell the tale. (She and her husband lived in the cabin shown at left, a structure

built after her return.) Her story was preserved in material written by her son John Ingles, published

in 1824, and her grandson John Peter Hale, published in 1886. The story became the basis of the

bestselling 1981 novel Follow the River by Alexander Thom. Earlier it was the basis for a

long-running historical play (often staged in Radford) “The Long Way Home” by Earl Hobson Smith.

These resulted in the ABC-network made-for-tv movie Follow the River in 1995 and the film The

Captives in 2004. Mary and the others were taken from a spot described as being part of the James

Patton tract. James Patton himself was one of the four killed in the raid, shot as he tried to fend

off a set of attackers with his broadsword. The tract was over a thousand acres in size, but it could

well be that on that infamous day, the Shawnee traversed Paulser’s land on their way

to the Patton and Ingles cabins. In a way, Paulser could be described as an adventurer simply by

choosing to reside in this unsecured territory.

Paulser must have been at least twenty-one years old in 1754 in order to have made a land agreement in

his own name. Since the transaction occurred at the very beginning of 1754, we can probably rule out a

birth in the calendar year 1733, but how much before 1733 he was actually born is guesswork as there

are no references to his age in surviving documents. His origins are unconfirmed, but his name suggests

he was Palatinate German, aka Pennsylvania Dutch. Several of his neighbors along New River were

individuals whose names appear on the list of Palatinate German passengers of the Winter Galley,

which arrived in Philadelphia harbor 5 September 1738. These neighbors were Adam Wall, Casper Berger

(also killed in the July 1755 Shawnee raid), Philip Harlas, and Johan Michael Preis (Price). It stands

to reason Paulser would have settled down “among his own kind.”

There is reason to think Paulser may have never viewed the New River property as a long-term home, but

more as an investment to develop and sell once he had found a better place. He had hardly arrived before

he began setting the stage for a move to Bedford County. The first indication is that he had 189 acres

surveyed in Bedford County 5 April 1755. This was before the Shawnee raid occurred but it may be that he

felt it prudent to have a haven to the east to retreat to if hostilities flared up. (Mary Draper Ingles

and her husband William spent an interval in Bedford County after the raid, requiring a period of respite

before they were willing to resume their lives along New River.) In the mid-1760s, Paulser was ordered by

the Bedford County court to

view a prospective road easement in order to help settle a lawsuit between two individuals, Abeshart

and Johnson, the implication being that the proposed road would run near land Paulser owned. But though

he was surely physically present in Bedford County from time to time during the 1750s and 1760s, he

seems to have been based in Augusta County until the end of that period. Some of the indications he

was still in Augusta County include a conviction in Sweet Springs District Court in 1764 of having

slandered one Joseph Ghent -- apparently Paulser had aired the opinion that the reason why Ghent owned

so many slaves was that Ghent enjoyed having his way with the females. In 1768, a man named George

Taylor purchased part of what had been the James

Patton tract along Crab Creek; in the deed descripton, Paulser is noted as a corner neighbor. The

turning point -- the juncture at which Paulser and family actually established a new home -- appears to

have come in 1769 when Paulser purchased 225 acres on both sides of Wilson’s Fork of Goose Creek from

previous owner Michael Woods. There were some lingering connections to the old stomping grounds. Paulser’s

name appears in 1773 and 1777 court records of Fincastle County -- the Crab Creek land having become part

of Fincastle in 1772, having been part of a huge version of Botetourt County from 1769 to 1772. In 1777,

Fincastle ceased to exist and the area became Montgomery County. However, these 1770s traces

are not compelling enough to imply Paulser had not yet moved to Bedford.

Paulser appears to have been a single man when he came to Augusta County, and the timing of his marriage

suggests he waited until he had exercised his option to buy the 440-acre Crab Creek parcel before he

was willing to become a family man. His wife was named Catharine. Her last name at the time of the wedding

was Miller, the surname stemming from her first husband. Her maiden name is uncertain. Various

possibilities appear in a few genealogies, but it is unclear what sources those possibilities arise from,

and so they will go unmentioned for now. She was a widow when she wed Paulser, the wedding most likely

taking place in 1760 or 1761. Her story was preserved in a hearsay fashion among her immediate direct

descendants. Bearing in mind that such word-of-mouth accounts have a tendency to drift off course from the

reality on which they are based, here is a summary of that story: Catharine was yet another Palatinate

German. Among other things, this means she may have gone by a German form of her name until arriving in

the colonies -- Katarina Müller being the likeliest form. She wed Mr. Miller in the late 1750s back in

Europe, and the newlyweds made plans to join relatives and friends who had already made their way to

Augusta County. Catharine, pregnant with her first child, made the voyage in 1759, but Mr. Miller stayed

behind to take care of some essential matters -- perhaps completing the process of selling off property

and/or other assets to create as much carrying-cash as possible -- and he fell sick and died before

embarking on the ship that was to carry him across the Atlantic. Catharine was perhaps already a widow by

the time she gave birth to son Henry Miller 6 December 1759 in Augusta County, though she may not have

known of her change of status until word of her husband’s death arrived the following spring. Once everyone

understood she no longer had a living spouse, the matchmaking would have been straightforward: There was

Paulser, a somewhat older man with plenty of property, and there was Catharine, a young widow

of similar ethnic and cultural background, in need of such a husband. Accordingly, the two were wed. Henry

Miller was the eldest of the kids they raised (barring the possibility that Paulser had an earlier family,

though there is no direct sign of one). Henry would in 1780 marry Sarah Jane Pearcy, daughter of John

Pearcy and Anna Margaret Spencer. He retained the name Miller throughout life, never becoming a Smelser

even though the only father he ever knew was Paulser. Apparently Paulser was a stickler for natural sons

being a man’s true heirs, and preferred not to formally adopt his stepson.

Catharine, who had been born in the 1738-41 time period, went on to give Paulser at least eight children,

not counting Henry Miller. These were John, Elizabeth (Betsy), Abraham, Stephen, Paulser, Jr., Rebecca,

Mary, and Jesse Smelser. John was almost certainly the eldest son and Betsy the eldest daughter, but

otherwise that sequence is not to be taken as the order of birth. Jesse, for example, was probably one

of the older kids. Unfortunately there does not appear to have been a family Bible record preserved as

happened in the case of the Pearcy family, and the timing and order of childbirths can only be guessed

at. There may have been other children who died young. The eight above are named in Paulser’s will.

Paulser was a man of significance in Bedford County, if perhaps not as major as John Pearcy. Court

records show that in 1772, he was appointed overseer of a road. In 1775, he had more land surveyed. In

1777, he contributed a significant sum for the so-called Cherokee expedition.

The close association of the Smelser and Pearcy families once they were both established along Goose

Creek is apparent via many individual bits of evidence: John served as an executor of Paulser’s will.

James Pearcy married Betsy Smelser, Henry Miller married Sarah Jane Pearcy, and Mary Pearcy married

Jesse Smelser. In the 1830 census, Henry Pearcy

and household appear on the very same page as John Smelser and Jesse Smelser and their households. In

1819, when Nicholas Pearcy acquired half of his brother Edmond’s portion of the original Pearcy estate,

Nicholas also bought the lot on Jones Fork of Goose Creek that contained the so-called “Smelser Meeting

House.” (Nicholas was by then a deacon of the local Beaver Dam Baptist Church and an advocate of Luther

Rice’s proposal to send Southern Baptist missionaries to Asia. Nicholas’s son George Pearcy was only six

years old in 1819 but the meetings in that hall may well have been where he was first encouraged to

become one of those crusaders.)

As the winter of 1777-1778 progressed, Paulser recognized that the health problems he was suffering

from might be terminal -- a correct assessment as it turned out. That his constitution failed at this point

suggests he may have been older than supposed, because a birth as late as 1732 would mean he was only

in his mid-forties at the time of his mortal decline. He made out his will 7 December 1777. By late the

following spring he was dead. Precisely what day he perished is not absolutely certain, but the will

was “proved” 25 May 1778 when Michael Carn, a witness to the signing, swore to J. Steptoe, clerk of the

Bedford County court, that it was the legitimate and legal document, and then was proven again on the

27th by witness Thomas Campbell, leaving the three executors, Catharine Smelser, John Pearcy, and John

Sharp, free to carry out its terms. Lacking any better date, 25 May 1778 appears in various genealogies

as Paulser’s precise death date.

Paulser’s will was kept within county archives and a clerk’s handwritten transcript of it from the 19th

Century survives today in the archives of the Bedford Museum. Paulser was very specific about his bequests

to his widow and children. We can all be grateful for that because it establishes the identities of the

eight children, one or two of whom would otherwise be forgotten. The nature of the bequests also sheds

light on the attitudes of the era, making clear that inheritance was an institution whose main purpose

was to ensure the control of property by white males. Catharine was given the home farm and everything

upon it, but only on the condition that she remain a widow. Remarriage would have required her to sell

all the personal property, slaves, and livestock and divide the money equally among the surviving kids.

The five sons were all given large chunks of land, with Stephen and Paulser, Jr. splitting the home farm

(Catharine in

essence keeping control of it not in her own right, but on their behalf), John and Abraham splitting a

parcel purchased some years before from Edmund Smith, and Jesse receiving the land newly surveyed in

1777. By contrast, the girls received diddly-squat, it obviously being taken as a given by Paulser that

whatever wealth they might have as adults would come from the husbands they would acquire, and so he only

needed to contribute a token amount toward their dowries. Betsy was given two cows and calves and ten

pounds in cash. Rebekah and Mary were given joint ownership of Peter, one of the household slaves, with

Rebekah given the option of claiming sole ownership as long as she paid Mary half of Peter’s value.

Apparently Paulser had even more prejudice toward step-offspring. Henry Miller is not mentioned in the

will. He got nothing. It is small wonder that he and Sarah Jane left Bedford County not long into

the 1780s in favor of Kentucky.

Catharine’s date of death is unconfirmed. Heirs along the Miller line have her death date as September,

1786. Other clues imply she died about 1794.

James Pearcy

James Pearcy was the thirdborn child of John Pearcy and Anna Margaret Spencer, born 4 May 1762 in

Buckingham County. To some degree he could also be thought of as the eldest son. He did have one older

brother, William, but William's paper trail vanishes with the inclusion of his name on the list of Bedford

County men who served in the Revolutionary War. It could be William did not survive the war. If he did, he

might otherwise have died in early adulthood. He is the only child of James and Margaret for whom there is

no marriage noted. Assuming he did die, this left James playing the role of eldest son from the 1780s

onward.

James was too young to fight in the early years of the war, but he was swept up in the

conflict later on. His pension application survives, complete with an account he dictated about himself.

He provided a long paragraph about his service (the length due in part to the need to include as many

details so as to substantiate his eligibility to receive benefits) and a four-sentence paragraph of

general autobiography. Four sentences isn’t much, but we are lucky to have it. On the positive side, since

he completed the application 25 September 1832 when he was already seventy years old, he was able to

supply a full tally of the four main places in which he dwelled over the course of his lifetime --

Buckingham County 1762-1768, Bedford County 1768-1809, Franklin County 1809-1817, and then Wayne County,

KY, where he would eventually pass away. Later his widow applied for benefits as his survivor. That

material is also in the file and gives us another scrap or two about James, including his death date of

23 June 1843.

James served about eight months in the Colonial Army as an infantry private under the command of Captain

David Beard and General Nathaniel Green, fighting in the Battle of Guilford in North Carolina and then

at the Battle of Yorktown, the decisive engagement of the war. In his pension file declaration, James

claims to have been “well acquainted” with George Washington and Lafayette. Given that James was not an

officer, he was probably exaggerating his familiarity with the two leaders. Undoubtedly there was some

sort of ceremony after the battle during which Washington and Lafayette personally thanked the men who

had fought and won, perhaps going as far as to shake their hands and exchange a few words with each

one face to face. That was probably the only type of occasion when James might have had the chance to

actually meet them and speak with them.

It was only a couple of years after coming back from Yorktown that James began his life as a

husband and father, matching his own father’s example of doing so at twenty-one. Actually, it was just

short of that age, with the wedding taking place 25 Apr 1783. His wife was Betsy Smelser. James was the

only one of the sons of John and Margaret to wed so early, the rest all waiting much longer. It is

worth wondering if it was a shotgun wedding. The best genealogies of the family have the first child,

John, born 22 March 1781. This could well mean there is an error in the record -- one prominent researcher

as it as 1784, which could mean he was part of a set of twins, the other being his sister Martha. If the

earlier date is correct, the couple conceived their first child three years before they wed, at a time

when James had just turned eighteen and Betsy was only about sixteen. This does not seem likely. Either

the date is not right, or it has some other explanation -- for example, it could be that John was

actually the son of James’s older brother William, adopted after William died. If there were complications

of any sort at the beginning of James and Betsy’s relationship, these stresses did not harm its longevity.

The pair were spouses for over sixty years, all the way to

the death of James in 1843. One side effect of them getting started young, though, was that their

kids were barely younger than James’s youngest siblings and it is sometimes hard to be sure which

generation of the family is reflected in Bedford County marriage records filed in the first two decades

of the 19th Century. Some of James and Betsy’s kids had names identical to those of some of his nieces

and nephews.

The children were born from the early 1780s up into the first few years of the next century, the last being

born about 1807 when Betsy was in her early forties. The precise number of children is unclear. There is no

doubt there were at least ten, but it is twelve if all of the possible children are included. In order of

birth, the full twelve are John, Martha, Jacob, Catherine, James William (known by his middle name),

Rebecca, Nathaniel (or Nathan), Charles, Mary (known as Polly), Matilda (Millie), and Elizabeth (Eliza),

as well as Sarah, whose birth-order position is uncertain -- she is mentioned as one of James’s heirs in

an 1849 land transaction. A man named Moses Wright bought land that year that James and Betsy had owned,

and all the living heirs were required to confirm that they had no further claim. Sarah is on that list,

but does not turn up in family records made prior to that date, hence the mystery. The children arrived

at an almost clockwork-like pace of every other year through the birth of Rebecca. But between Rebecca and

Nathaniel is a gap of six or seven years. The odds are high that at least a couple of children were born

during this span, say one about 1892 and another in the middle of the decade. Sarah’s birth could easily

fit into one of these positions, but aside from that possibility, James and Betsy may have lost one or

more babies whose existence has left no detectible trace. There is also the possibility James was not

siring children during these gaps because he was absent from the home. The 1790s was a period when

European-Americans were rapidly pushing out the native tribes of the lands just west of the Appalachian

range. The economic opportunities for someone with enough cash to obtain land or, for instance, fund a

sawmill in a fast-building locality, were perhaps too good to pass up. Sometimes these frontier areas were

too raw to be suitable for a wife and kids, so it could be James went on his own. There is no direct

evidence now that he was involved in such a foray, but it is easy to imagine he may have indulged this

urge. His sister Sarah and brother-in-law Henry Miller had been among the very earliest pioneers of

Lawrenceburg, KY, arriving at that settlement in approximately 1784. They continued to reside there until

the 1820s. James might easily have taken advantage of their home as a base from which to investigate

opportunities in central Kentucky.

If James did not “check out things out west” in the 1790s, then we have to assume he spent his twenties,

thirties, and most of his forties simply being a gentleman farmer and minor official of the Goose Creek

area of Bedford County, serving as his father’s main lieutenant. We know from his pension application that

he and Betsy moved in 1809 to neighboring Franklin County, VA. By then, his mother was probably deceased.

His father was transferring ownership of Bedford County land to other sons; it stands to reason John may

have had a parcel in Franklin County that was given to James. The move was probably a small one -- perhaps

only a few miles. It was not more than a couple of dozen miles. There is one other possible impetus for

this move. James and Betsy’s son Jacob was charged with a felony 6 June 1807. Jacob went “on the lam” to

Botetourt County and eventually on to Randolph County, WV, where he operated under the Piercy and Percy

spellings of the surname, perhaps as a way of hiding his origins. This incident may have negatively

affected the reputation of James and Betsy, spurring them to head for Franklin County after a couple of

years of coping with the gossip. Another potential blow to their reputation may have been the birth of

their grandson Nathan Pearcy in about 1808. Nathan Pearcy, who as a grown man would eventually settle in

Daviess County, MO (a place where many Bedford/Franklin County folk moved in the late 1850s and early

1860s), appears to have been born out of wedlock to James and Betsy’s daughter Catherine Pearcy a few

years prior to her marriage to John Richardson.

The pension application refers to another move, this one bringing James and Betsy to Wayne County, KY in

March, 1817. This was thoroughly unlike the earlier move to Franklin County. It represented a “clean

break” and probably is a strong indication that James’s father had died by then, meaning that James no

longer had either of his parents alive to anchor his bond to the area where he had been raised. Moreover,

he may have received enough of an inheritance to fund a big, bold change of venue. Why he and Betsy

would come to roost in Wayne County is not obvious, though. Did they want to get away from their past

associations? If so, Wayne County was a good hiding place. Over the decades various members of the

clan would also choose to leave Bedford County and its region, but they would go to such places as

West Virginia, the Ohio River Valley, Wisconsin, Iowa, Missouri, Texas, and even the Far West. None

came to Wayne County. The handful that did eventually make it into Kentucky set themselves down in the

eastern or northern portions of the state, such as Sarah Jane Pearcy and Henry Miller had done when

choosing to live in pioneer Lawrenceburg.

The clean break aspect was even true of some of James and Betsy’s immediate family. Most of the kids had

come along to Franklin County, but a full six declined to move to Wayne County. Before their lives were

done, these six would be widely scattered. Of that group, John died in Indiana, Jacob in West Virgina,

Rebecca (probably) in Wisconsin, and Charles back in Bedford County. Only five children came to Wayne

County. Three of them were daughters Polly, Matilda, and Eliza, who didn’t really have much of a choice

because they were still unmarried minors as of 1817. Another was Nathaniel, who was twenty at the time of

the move but had not yet married, so again his decision was influenced by the fact that he had not yet

established himself outside his birth household -- Nathaniel would spent sixteen years in Wayne County

before moving to Morgan County, IL and then, a couple of decades later, to Decatur County, IA. The one

child who deliberately chose to be part of the migration, but did not have to be, was married son

William. This may be a clue. It could be that William was the person primarily responsible for the

decision to move. It could be that William was the son who was helping maintain the family farm in

Franklin County. Once he set his sights on Wayne County, it would have left James and Betsy in the lurch

unless they came along.

Wayne County was an out-of-the-way spot back then. This is still true even today, with the 2000 census

showing fewer than 20,000 human inhabitants. The Pearcy clan is well represented there. William and

his wife Senah (Clatcher) had a large family, and large (or even huge) families tended to be the mode

among their children and grandchildren. Many descendants remain within the county. This is also true of

a fragment of Polly’s line. Given the exponential increase in numbers

with each generation, it would not be out of the realm of possibility that a thousand descendants of

James and Betsy live in Wayne County today. That would be five percent of the local population.

Being in Wayne County also exaggerated the tendency for the family name to be recorded under spellings

other than Pearcy. (This was true elsewhere, but not to the same degree.) Well over half of the modern-day

descendants of James William Pearcy use the Piercy variation. When researching the 19th Century documentation

of the family in Wayne County, one must search not only for Pearcy, but for Piercy, Piercey, Peircy, Peercy,

Pierce, Perry, and even Powers (the latter perhaps being due to the proximity of Wayne County neighbors

named Powers). The pension file application was submitted under the Piercy variant, though within the

document it is also rendered as Pearcy.

James reached the age of eighty-one, showing more longevity than his siblings except possibly for Henry,

who may have reached eighty-two. He and Betsy may have maintained a home of their own until near the end,

but if so, they had plenty of younger family members with them. It is also likely that James gave up the

role of head-of-household well before his death, ceding it to son William, or sharing a home with

Polly and son-in-law Lorenzo Dow Kannatzer. Betsy is shown in the 1850 census as a widow residing with

the latter pair and their kids.

Betsy is assumed to have still been in Wayne County when she passed away. Her precise date of death is

not available, but it is assumed to be some time in the first half of 1857. She had qualified in 1848

for a widow-of-a-veteran payments of $13.33 per month for the rest of her life. This stipend was paid

in lump sums of eighty dollars every six months in March and September. The last payment to her went out

in March, 1857. This can reasonably be taken to mean the bureaucrats were informed that she had died and

so the September, 1857 payment was not sent. Even to have reached calendar year 1857 means she was at least

ninety-two years old when she died. In the March, 1855 renewal of the pension application, she claimed

to be already be ninety-seven, but this can be taken as the standard sort of exaggeration that occurs

whenever the matriarch of a clan gets so old everyone starts saying, “Wow, she is almost a hundred years

old!” and the woman herself is too deep into her senility to offer a correction.

James Martin and Rebecca Pearcy

Much of what there is to say about James Martin and Rebecca Pearcy’s origins or their youth has already

been described above or in the biography of their son Nathaniel. They probably met in Franklin County,

VA soon after Rebecca and her family moved there. The pair were wed in late 1811.

By early 1812, they appear to have set out on their own without any of their family members and

forged a life for themselves in Monroe County, in what is now West Virginia. The paper trail is

blank for the next twenty-five years. When it comes to the usual footprints such as censuses, tax

lists, deeds, court case files, the family is invisible. We are left with indirect measures to tell

us how they lived their lives.

We have the hint that James may have been more than “just a farmer.” For one thing, he married Rebecca,

and she was not “just a farm wife” material. She was from an educated and prosperous family, and she

appears to have been educated herself -- no small thing for a woman of her era. Moreover, Monroe County

was not the sort of place to go just to farm. Yes, there were fertile bands of flat alluvial soil along

some of the waterways, but Monroe County’s greatest economic asset was its abundance of fast streams,

perfect for the water power needed for mills -- sawmills, grist mills, woolen mills. Rebecca came from

mill country as

well, and was the daughter of a man whose clan’s wealth back in England had come from textile milling.

Their sons Nathaniel and Isaiah founded mills. James is highly likely to have had a career as a miller

of some sort. If he had been just a farmer, some or all of his sons would have been just farmers, too. But

of the four sons whose lives can be examined, all had non-agricultural professions.

Precisely where they lived is another part of the blank, and again, it is the indirect evidence that

gives us any clue at all. The birthplace stats columns for their children in censuses taken in the second

half of the 1800s confirm James and Rebecca maintained their home in West Virginia throughout the years

the kids were being born. And though James and Rebecca are invisible, the same is not true of John Burwell

or Jacob King, who would become their sons-in-law in the late 1830s. Logically, the Martins

lived near the Burwells and the Kings. Together, the clues add up to a Martin home somewhere in the

northern part of Monroe County near the border with Greenbrier County, with Second Creek (a teeny-tiny

hamlet, then and now) being a valid spot to push the pin into the map.

One of the tiny scraps we have that frames a lifestyle scene is that music was nurtured within the family.

This would be true down through the generations. Some descendants even depended upon music as a source of

income, examples being Nathaniel’s great-grandaughters Hazel Cannon Rodgers, a piano teacher, and

Margaret Eliza Hodge, a violin teacher. All of the sons of James and Rebecca were said to have played

the fiddle. One can just imagine the family members and neighbors gathered for a Saturday night

Appalachian hoedown in the 1830s.

The children began arriving at once and at a pace that left Rebecca pregnant three quarters of the

time for the first half-dozen years of the marriage. The pace of later births was somewhat more sedate,

but fast enough that by the end of the 1820s the tally had come to ten. They were Sydney, Redmond, Isaiah,

Elias, Nathaniel, Rebecca, Nancy, Samuel, Polly, and Charles. We have nine of the names from the list in

Nathaniel’s 1901 biographical sketch, and that sketch confirms the total came to ten. The one missing

child is Samuel, whose name is included in the genealogy created by Nathaniel’s great-granddaughter

Sarah Jeanette Hodge in the 1940s. Sarah’s source for the name Samuel is unknown and it remains an open

question whether she was correct.

Finally in the late 1830s, the paper trail resumes, and even a skeptic would have to agree the Martins

were in Monroe County by then. Monroe County’s records include the marriage book entry for Sydney Martin,

who married Jacob King 16 March 1838. A couple of years later the 1840 census was gathered, and

James is finally noted as a Monroe County head-of-household. The 1840 census was the last Federal census

that failed to list the names of all the occupants of a dwelling, but the ages and genders are noted,

yielding a tally that is perfectly consistent for a household composed of James, Rebecca, Sydney,

son-in-law Jacob King, and the latter’s kids (some from his earlier marriage), along with Samuel and

Charles Martin, the two boys still young enough to be at home. Sydney and Jacob and family reappear in

this same locale in the 1850 census.

By that 1850 census, James and Rebecca were no longer themselves residing in Monroe County, though. After

thirty years or more, they had finally moved on. They must have felt free to do so given that all of their

offspring except Charles were grown. Taking Charles along, James and Rebecca moved to Raleigh County, VA

(now WV). The pair appear in Raleigh County in the 1850 census. What spurred this move is unclear except

that at about this time quite a few people of Monroe County moved to Raleigh County, including some who

had been fairly close neighbors of the Martins.

That 1850 census enumeration is peculiar. All of the surviving children are listed as if they were there

dwelling with the old couple. This was not even close to being the truth. The only child who is likely to

have been a member of the household was Charles, then about twenty-one years old. Some were very far away,

the farthest example being Isaiah, who was out west panning for gold in the Trinity Alps of northern

California. It was as if the enumerator asked James to list all the children living with him and he,

perhaps hard of hearing or a little senile, did not hear the “with him” part of the sentence and listed

all his living children, which at that time consisted of Sydney, Redmond, Isaiah, Nathaniel, Rebecca,

Nancy, and Charles, the other three having already died.

In the early 1850s, with Nathaniel and Isaiah running the

extremely successful sawmill in Martintown, many of the other family members were drawn to the vicinity.

James and Rebecca -- probably still with son Charles in tow -- were among those that gave in to the

tropism. Family records do not say necessarily say they lived with Nathaniel. They might have instead

been with daughters Rebecca Burwell or Nancy Mew, both of whom lived slightly south of Martintown on the

Illinois side of the state line. However, it is reasonable to assume James’s final days were

spent in Martintown. There is no question he was buried there. James passed away 9 October

1856 -- the date happend to be his and Rebecca’s 45th wedding anniversary. He became the second family

member to be buried at the crest of the hill above the mills and main house, in what would become the

Martin cemetery. (The first was his grandson William Martin.) His tombstone states he had lived

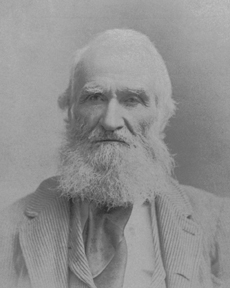

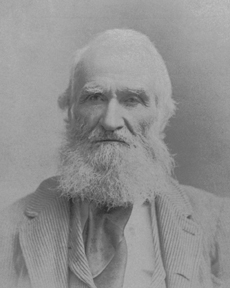

seventy-seven years (this conflicts with census records that put his birthdate in about 1775). (Photo

at left taken by Robert Carpenter 1993.)

In the early 1850s, with Nathaniel and Isaiah running the

extremely successful sawmill in Martintown, many of the other family members were drawn to the vicinity.

James and Rebecca -- probably still with son Charles in tow -- were among those that gave in to the

tropism. Family records do not say necessarily say they lived with Nathaniel. They might have instead

been with daughters Rebecca Burwell or Nancy Mew, both of whom lived slightly south of Martintown on the

Illinois side of the state line. However, it is reasonable to assume James’s final days were

spent in Martintown. There is no question he was buried there. James passed away 9 October

1856 -- the date happend to be his and Rebecca’s 45th wedding anniversary. He became the second family

member to be buried at the crest of the hill above the mills and main house, in what would become the

Martin cemetery. (The first was his grandson William Martin.) His tombstone states he had lived

seventy-seven years (this conflicts with census records that put his birthdate in about 1775). (Photo

at left taken by Robert Carpenter 1993.)

Rebecca went on to marry again within a year or so of his death -- a somewhat astonishing development.

Her new husband was a Norwegian Lapp and his name appears in various forms in sources, due in part to

the different way names were composed in his homeland, and in part to his accent. Louis was the American

form of his first name, and the “most correct” spelling of his last name seems to be Enger. He also went

by Lewis Johnson, apparently because he seems to have off-and-on resorted to the Scandinavian naming

custom, using Johnson because his father’s first name was John. In the 1858 court case in which he

tried to seize power-of-attorney over Nathaniel’s estate, his name is transcribed as Lewis John Engert.

It is rendered as L.G. Anger in the 1860 census. The latter document is the only one available that

includes an age. It said he was thirty-nine. This does not seem credible and is probably an error. It is

unlikely Rebecca managed to attract the attentions of a man thirty-one years younger than herself -- unless

perhaps his only reason for pursuing the union was his hope that it would allow him to gain control of

Nathaniel’s considerable wealth. Rebecca was still alive as of the 1860 census (residing in Martintown

with Lewis). She does not appear in the 1870 census, when she would have been eighty years of age. Chances

are high she passed away during the 1860s.

And so we have come down through history and arrived at Nathaniel himself. His own biography page covers

his life in full and there is no need to cover it again here, but it is appropriate to offer capsule

biographies here of each of his siblings:

Five of the group appear to have remained in the general vicinity of their birth, venturing no farther

west than the Appalachian Mountains:

Polly died in childhood. She was probably one of the last to be born, perhaps even later than

Charles, who is otherwise assumed to have been the very youngest. In any event, Polly never had the chance

to live anywhere other than Monroe County.

Sydney, the eldest, was something of an old maid (i.e. in her mid-twenties) when she married

Jacob King 16 March 1838. Jacob was actually younger than she by about three years. He had been married

at about age twenty to Malinda Meadow and had sired at least two children with her before her untimely

death. Sydney helped raise these two stepsons, and in addition, she and Jacob had eight more

children (among them the aptly-named Monroe King). She and Jacob and their youngsters appear to have

stayed put in Monroe County for the duration of their fifteen-year marriage, that home perhaps being none

other than the home of James and Rebecca Martin, which the old couple left to the younger ones when they

moved to Raleigh County. They definitely shared a home of some sort with James and Rebecca for at least

two years, because the family members are all enumerated together in the 1840 census. Sydney did not have

the good fortune to finish raising her children to adulthood. She died 7 May 1853 of measles. Her death

register entry is the main source to confirm that James and Rebecca settled in Monroe County as newlyweds,

because Sydney’s birthplace is given as Monroe County. Jacob King was the informant. The death register

entry is also the only time in 19th Century sources that her name is spelled Sydney -- the standard female

spelling. Elsewhere it is always Sidney. Jacob King married his third wife Jane Massie, a widow with many

children of her own, about ten weeks after Sydney’s death. Jacob and Jane then moved a short distance to

Greenbrier County (now in WV), where he passed away about 1860. Despite her somewhat truncated life, Sydney

now stands as ancestress of a huge clan. At least seven of her biological children reached adulthood

and married and by now the list of her descendants is well into the hundreds. For whatever reason, an

unusually large proportion of those descendants lingered (and survivors continue to linger) in West

Virginia, quite in contrast to the dispersal pattern shown by the descendants of Sydney’s siblings.

Redmond settled in the Kanawha Valley of what is

now West Virginia. He arrived there in either the 1830s, or in the early 1840s. He resided for decades at

Alum Creek along the Coal River in Kanawha County just east of the Lincoln County line. He was no doubt

lured to Kanawha County by the prosperity stemming from the salt industry. The Kanawha River’s brine fields,

known since the era of Daniel Boone as the Great Buffalo Lick, represented a major source of this key food

preservative for the United States during the middle decades of the 19th Century. Redmond was not a salt

worker himself, though. He was a blacksmith and farrier. (Given that he had some land, he was also a

farmer, but not in a core-career sort of way.) In a history of the community of Alum Creek he is called a

shoe-maker, a reference to horseshoes, not human footwear. That history refers to Redmond as the person who

first noticed the absence of a neighbor’s wife and the odd behavior of the missing woman’s two young

children, which in turn made the community aware that the neighbor had, in fact, murdered his wife and

placed her body at the bottom of the Coal River. The body was found, the man was convicted of the crime,

and was hung. That incident occurred in 1853. By then, Redmond was ten years into his long marriage to

Elizabeth Midkiff, the mother of his six known children. She was part of two large clans who pioneered

Kanawha County, the Turleys and the Midkiffs. (The aforementioned murderer was Preston Turley, who was

probably a cousin of Elizabeth.) There were so many descendants of these families in the area that it was

inevitable that there was further mingling. Redmond and Elizabeth’s son Charles and Charles’s daughter

Celisha also married Midkiffs. There was even mingling among Redmond and Elizabeth’s direct descendants,

as when their great-grandchildren William W. Tyler and Florence Lenora King married one another in 1935.

(William and Florence were each other’s second cousins.) Members of the combined Martin/Midkiff clan

remained in Kanawha Valley well into the Twentieth Century and some are still to be found there. Redmond

may have had a middle name of Edward. He appears in the 1850 census as Edward Martin. However, this is the

only source that refers to him by that name and it may simply be an enumerator’s error. Redmond

became a soldier at over fifty years of age, joining the Union Army in 1864. Judging by his Civil War

pension file, he did not see combat, and in fact appears to have been posted only some ten miles from home

in Charleston. His role in the military was the same as in his civilian life -- he was a blacksmith. Like

many Civil War soldiers, the biggest risk to life he faced was from camp sickness, and indeed he was

hospitalized for a stretch in the winter of 1864-65. He recovered well enough to be discharged and was

returned to active duty for a period prior to being mustered out. He came back to Alum Creek at the close

of the war and survived until 1882, falling just shy of achieving the Biblical three-score and ten years

of lifespan. It is obvious he knew his end was coming at least a few weeks in advance because he wrote his

last will and testament 21 March 1882, referring in it to his ill health, and then the will was proven on

11 April 1882, Redmond having died some time during the interval between the 21st and the 11th. Elizabeth

passed away five years later. Both spouses are buried in Midkiff Cemetery. (The photograph at right,

taken by Redmond and Elizabeth’s descendant Terri Wiseman Smith, shows this cemetery. It is not known if Redmond

and Elizabeth’s headstone is in view.) The six children were Lucetta, Charles William, Susan C., James,

Mary Ann (“Polly”), and John. The only one of those six to live a full life was Charles, who died at age

seventy-one. James and John did not reach adulthood. Lucetta died in her twenties, only a few years after

starting a family. Polly also died in early motherhood, but was still alive when Redmond wrote his will.

Most of Redmond and Elizabeth’s grandchildren were the issue of Charles or Susan. The latter made it into

her fifties.

Samuel probably also stayed in the Appalachian region. He is assumed to have died young

because his name is not included in the 1850 census with James and Rebecca. That enumeration included

all children known to be alive and none of those known to be dead, so since Samuel’s name is not there,

it stands to reason he was dead. He is probably one of the two teenaged males noted in the 1840 census,

so he may have reached adulthood before he expired.

Elias lived to adulthood or close to it, but he died by no later than 1847 because his

namesake nephew, Nathaniel’s oldest son, was named for him, and it was a posthumous honor.

The other five children of James and Rebecca came west. Isaiah came with Nathaniel (or Nathaniel came

with Isaiah), as noted on Nathaniel's biography page. The pair could be called adventurers, exhibiting

the classic tendency of 19th Century American youngsters to boldly set off westward into frontier territory

just to see what they could make of themselves -- the famous Manifest Destiny syndrome. Eventually the other

three siblings did migrate, but they did not do so until Nathaniel’s mill was up and running and Martintown

and its immediate area represented a secure and stable place to put down roots.

Isaiah and his life are somewhat covered within Nathaniel’s biography since the two brothers

were so closely associated through their twenties and thirties. The point at which there destinies began

to separate was when Isaiah began substituting Nathaniel’s company for that of his wife and her family. He

wed Mary Gibler 9 April 1849, probably in Winslow, IL. Mary was a daughter of Lewis Gibler and Margaret

Van Matre, a couple who had been among the first settlers of Stephenson County. The Giblers had come

from Ohio, and it is possible they had journeyed to northern Illinois as part of the same migration

that included Hannah Strader and her family. Early into the marriage Isaiah left for the gold fields

of the Trinity Alps in California (just west of Mount Shasta -- a separate gold rush from the concurrent

frenzy going on in the Mother Lode), leaving Mary and infant son James T. Martin to lodge with her parents

in Oneco Township in Stephenson County. The 1850 census for Shasta County shows that one of

Isaiah’s fellow prospectors was Jesse Gibler, his new brother-in-law. Both Isaiah and Jesse returned

to the Pecatonica River area early in the 1850s, after which Isaiah helped Nathaniel run the mills.

Isaiah’s presence was surely a factor in expanding from just a sawmill to a gristmill as well. The

latter business began operation in 1854. Isaiah lingered in Martintown until at least the end of 1857.

A letter written by former coworker John Warner 17 November 1857 happens to mention that Isaiah

was then in the final stages of dredging out the mill race for the Bradford & Hicks sawmill, silt having

made the mill near useless for much of that calendar year. Then not long after, perhaps as early as

December, 1857 and perhaps having had some sort of disagreement with Nathaniel given how thorough the

subsequent separation became -- Isaiah left for Van Zandt County, TX with Mary and their little daughter

Minnie. Early in the year 1860, second daughter Addie was born. That completed the family, adding up to a

very small brood by the standards of the time, made even smaller due to the death of James T. Martin in