Mary Lincoln “Tinty” Martin

Mary Lincoln Martin, the eleventh of the fourteen children of

Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, was born 12 August 1863 in Martintown, Green County, WI. Obviously

named after the nation’s then-current First Lady, she was known to the family as Tinty. It is not known

how she obtained such an unusual nickname, which sometimes appears in family correspondence as Tintie

and Tinta, except that it might somehow have come from her middle name. How one gets “Tinty” from

“Lincoln” is a mystery, but the nickname was part of a set shared with her brother Abraham Lincoln

Martin, the set being Linky and Tinty. Perhaps Tinty evolved from an earlier version, Tinky being the

prime possibility.

Mary Lincoln Martin, the eleventh of the fourteen children of

Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, was born 12 August 1863 in Martintown, Green County, WI. Obviously

named after the nation’s then-current First Lady, she was known to the family as Tinty. It is not known

how she obtained such an unusual nickname, which sometimes appears in family correspondence as Tintie

and Tinta, except that it might somehow have come from her middle name. How one gets “Tinty” from

“Lincoln” is a mystery, but the nickname was part of a set shared with her brother Abraham Lincoln

Martin, the set being Linky and Tinty. Perhaps Tinty evolved from an earlier version, Tinky being the

prime possibility.

Tinty and Linky were a tandem of sorts in childhood, though the 1870s was very much a time when boys

did boy stuff and girls did girl stuff. It must have been quite a shock to Tinty when her brother

drowned in the Pecatonica River in 1879 at only eighteen years of age.

Tinty married Elwood Byron Bucher 30 January 1882 in Monroe, Green County. Elwood was often better

known as E.B. Bucher. The eldest son of Jacob Bucher of Pennsylvania and Matilda Gilbert of Maryland

and one of many children, Elwood had been born 14 February 1861 in Amboy, Lee County, IL. He had spent

his childhood there and in adjacent Ogle County before the family came north to Jordan Township, Green

County, WI prior to 1880, by which time he was almost old enough to be out on his own. His father worked

for years as a miller, and had apparently passed those skills along to Elwood, who at the time of the

wedding was a miller working at the Martin grist mill.

Tinty (shown at right at about age seven) was one of

the youngest children of Nathaniel and Hannah, so it was only natural that her own children were among

Nathaniel and Hannah’s youngest grandchildren, and there are strong indications Hannah doted on them. The

matriarch had plenty of opportunity to do so because Tinty remained emotionally and geographically close

to her parents. Tinty and Elwood and their brood

dwelled first right in Martintown and then, some time in the 1890s, moved only a tiny bit south over

the state line to Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. (Shown below at right is their home a hundred

years after they moved into in it.) Tinty and Elwood had the five children whose biographies can

be found by clicking on their names at the bottom of this page, as well as a set of male twins, born

25 September 1890 in Martintown. No source provides a name for either of the twins, who were probably

born prematurely as twins often are. This lack of known names implies they died very early in their

infancies. However, it is believed they were not stillborn, or their existence would probably not

have been noted at all. Instead, they are referred to in family genealogical notes and in Elwood’s

obituary. The 1900 census plainly states that Tinty had given birth seven times and confirms that

two had died. Their birthdates were not recalled within the family, but by 1890, Green County was

beginning to make a practice of keeping birth records on file, and so the Wisconsin Birth Index was

used to determine when they came into the world. Whether either or both of the twins survived past

the 25th is not yet known.

Tinty (shown at right at about age seven) was one of

the youngest children of Nathaniel and Hannah, so it was only natural that her own children were among

Nathaniel and Hannah’s youngest grandchildren, and there are strong indications Hannah doted on them. The

matriarch had plenty of opportunity to do so because Tinty remained emotionally and geographically close

to her parents. Tinty and Elwood and their brood

dwelled first right in Martintown and then, some time in the 1890s, moved only a tiny bit south over

the state line to Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. (Shown below at right is their home a hundred

years after they moved into in it.) Tinty and Elwood had the five children whose biographies can

be found by clicking on their names at the bottom of this page, as well as a set of male twins, born

25 September 1890 in Martintown. No source provides a name for either of the twins, who were probably

born prematurely as twins often are. This lack of known names implies they died very early in their

infancies. However, it is believed they were not stillborn, or their existence would probably not

have been noted at all. Instead, they are referred to in family genealogical notes and in Elwood’s

obituary. The 1900 census plainly states that Tinty had given birth seven times and confirms that

two had died. Their birthdates were not recalled within the family, but by 1890, Green County was

beginning to make a practice of keeping birth records on file, and so the Wisconsin Birth Index was

used to determine when they came into the world. Whether either or both of the twins survived past

the 25th is not yet known.

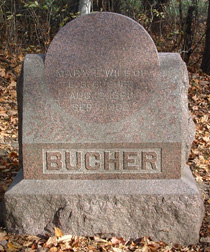

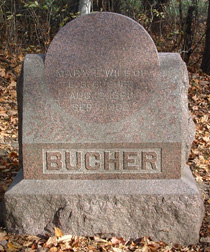

Tinty survived a greater number of years than eight of her siblings. Nevertheless, she did not escape

the curse of short lifespan. She passed away at the age of only thirty-nine, her death taking place 1

September 1902 in Winslow. Her death record states she perished of peritonitis and salpurgitis,

complicated by septic metritis. In layman’s terms, her upper reproductive tract became severely

infected. The cause may well have been an ectopic pregnancy. However, at that point in medical

history, it was not unheard of for women’s deaths to be attributed to reproductive tract sepsis when

actually the problem was a burst appendix. Either way, if Tinty had lived in the era of surgery and

antibiotics, she might not have succumbed. That makes her death seem particularly tragic to those of

us who are alive today, but it was tragic enough at the time. Imagine the horror of Nathaniel and

Hannah, to know that they had survived more than half the children born to them. Tinty was the

penultimate child of the couple to be laid to rest in the private Martin cemetery at the crest of the

hill above her parents’ house. (Her gravemarker is shown below left.) Her brother Horatio’s

remains would be interred there less than four years later. (Tinty’s body was later moved. Details

are at the bottom of this biography.)

Tinty and then Horatio’s demise set the stage for their

surviving spouses, Elwood Bucher and Laura Hart Martin, to find solace from their loneliness in

each other. They would marry 21 March 1907 in Chicago, meaning that the children of Tinty and

Horatio would henceforth be not only first cousins, but step-siblings.

Tinty and then Horatio’s demise set the stage for their

surviving spouses, Elwood Bucher and Laura Hart Martin, to find solace from their loneliness in

each other. They would marry 21 March 1907 in Chicago, meaning that the children of Tinty and

Horatio would henceforth be not only first cousins, but step-siblings.

Elwood slipped easily into the role of boss of the Martin mills. He moved into the home Laura and

Horatio had shared. In the long run Laura would be his wife over a greater period than Tinty had

been. The couple finished raising Laura’s youngest three children as well as Ralph Bucher, who had

only been two years old when his mother died. The other Bucher kids did not participate in this

shared household because by early 1907 they were old enough to have established themselves

independently, even Blanche, who was a school teacher soon to marry Tecumseh E. Claus. Inasmuch as

Elwood and Laura’s home was right next door to that of Hannah Strader Martin, they surely provided

some care to the elderly widow, though the brunt of this responsibility fell upon Juliette Martin

and her husband E.E. Savage, who had moved back to Martintown and back into the original Nathaniel

Martin family residence after some years spent in the Pacific Northwest.

Elwood was the last major steward of the family legacy business. That he was the last was not due to

any failure on his part. In fact, he seems to have been a particularly capable successor of Nathaniel

and Horatio, and this competence was a good thing, because he faced challenges from the early days

of his tenure. He was not allowed the luxury of simply letting the businesses operate as they had over

the previous half-century and more. The globalization and consolidation of commerce was wiping out

cottage industries right and left. The production of flour had once been a matter of local farmers

growing their own wheat and bringing it to the nearest mill to be processed. Lumber had once been

delivered by ox-drawn wagons and barges, and the shorter the distance the wood had to travel from

forest to mill to construction site, the better and cheaper for all concerned. Nathaniel Martin had

in a sense enjoyed a monopoly. But by 1905 to 1910, the operations he had brought into being were

becoming quaint. Old customers would still come calling, but only if the prices remained competitive

with those of the large, distant suppliers. Elwood did not stand idly by and let himself be a victim

of changing times.

Elwood embraced the new era, seeing new opportunities. At this

point, it was taken as

a given that electricity would soon be the standard way every American home would be lit. Electrical

appliances -- stoves, refrigerators, vacuums -- were poised to become equally common, if not quite

so soon. In Martintown and Winslow, there was as yet no electrical utility company. Elwood saw that

he could tap the power of the mills’ waterwheels and meet that demand. In 1909 he was awarded a

contract by the town of Winslow to supply enough electricity in the evenings for the street lights,

allowing the gas lights to be retired. By September of that year -- a month ahead of deadline -- he

delivered on his promise. The electric plant eventually became the mills’ prime reason to exist, ahead

of flour and lumber.

Elwood embraced the new era, seeing new opportunities. At this

point, it was taken as

a given that electricity would soon be the standard way every American home would be lit. Electrical

appliances -- stoves, refrigerators, vacuums -- were poised to become equally common, if not quite

so soon. In Martintown and Winslow, there was as yet no electrical utility company. Elwood saw that

he could tap the power of the mills’ waterwheels and meet that demand. In 1909 he was awarded a

contract by the town of Winslow to supply enough electricity in the evenings for the street lights,

allowing the gas lights to be retired. By September of that year -- a month ahead of deadline -- he

delivered on his promise. The electric plant eventually became the mills’ prime reason to exist, ahead

of flour and lumber.

Elwood’s main assistant was Charles Lewis Buss, the husband of his daughter Rose Marie Bucher. Elwood

was reaching fifty years old and as he saw it, Charles would make an ideal successor. Other young males

of the family were tapped to help with the business, whether it be flour milling or lumber cutting or

running the dynamo. These included Fay Martin and later, as teenagers, Ralph Bucher and Clark

Martin. Having Charles on hand, living with Rose and their offspring a stone’s throw from the huge mill

buildings, meant Elwood was free to move back to Winslow, so as the “aught” years of the 20th Century

turned into the 1910s, he and Laura and their boys did so. Life had become secure again, with a seeming

bright future ahead, after a very trying decade that had opened with the death of Tinty, seen the deaths

of Nathaniel and Horatio and the departure of Nellie Martin Warner and most of her family, and had ended

with the demise of Arley’s young husband Frank Ritter.

The good times lasted only about five years, then

Elwood’s doctor son Claude was killed by an automobile crash in late 1915 while making a house call. At

the end of 1918, Blanche succumbed to the great influenza epidemic. Both died in their early thirties.

About 1920, Elwood’s health failed. The precise nature of his malady is not well described in surviving

notes, but he was weak enough he sometimes resorted to a wheelchair (though he was capable of standing

upright, as shown in the photo at left, with Laura outside their home). Grandson Lyle Smith recalled

that as an adolescent he was not allowed to see Grandpa Elwood because he had some sort of “bad disease.”

This may have meant Elwood had a condition that was contagious or unsightly, tuberculosis being the

prime candidate, or it could mean he had something morally repugnant, such as syphillis. Much of his

care fell to his brother John, who moved into the Winslow home with Elwood, Laura, and their

“grown-sons-still-at-home” Fay and Ralph, Clark having moved to Washington state, where he worked at

the creamery of Elwood’s brother Charles Benedict Bucher. Whatever it was, it was chronic. Extended

forays to the South and the West, taken in hope of therapeutic benefit, did nothing to help.

The good times lasted only about five years, then

Elwood’s doctor son Claude was killed by an automobile crash in late 1915 while making a house call. At

the end of 1918, Blanche succumbed to the great influenza epidemic. Both died in their early thirties.

About 1920, Elwood’s health failed. The precise nature of his malady is not well described in surviving

notes, but he was weak enough he sometimes resorted to a wheelchair (though he was capable of standing

upright, as shown in the photo at left, with Laura outside their home). Grandson Lyle Smith recalled

that as an adolescent he was not allowed to see Grandpa Elwood because he had some sort of “bad disease.”

This may have meant Elwood had a condition that was contagious or unsightly, tuberculosis being the

prime candidate, or it could mean he had something morally repugnant, such as syphillis. Much of his

care fell to his brother John, who moved into the Winslow home with Elwood, Laura, and their

“grown-sons-still-at-home” Fay and Ralph, Clark having moved to Washington state, where he worked at

the creamery of Elwood’s brother Charles Benedict Bucher. Whatever it was, it was chronic. Extended

forays to the South and the West, taken in hope of therapeutic benefit, did nothing to help.

Elwood off-loaded one concern by selling the dynamo to a consortium based in Lena, IL (a village

half a dozen miles south of Martintown). He kept title to the other mills for the time being. As he

entered his last decade of life, one of the thoughts that comforted him was that he was to leave these

remaining family

businesses in the custody of a hand-picked, well-trained successor. Alas, Charles Buss

chafed at the role he was asked to play. He longed to do something else with his life. Among other

things, he wanted to become a clergyman. Rose, too, felt the calling to preach, unusual though that was

for a woman of her generation. In the early 1920s, Charles lost three fingers in an accident at the

mills. He took this as a sign that he was not living the life meant for him. Charles and Rose moved to

a new home in Vermilion County, IL, near Danville. Possible family replacements such as Ralph or Fay,

or Laura’s grandsons Leon and Lyle Smith, did not have the aptitude or inclination -- or in the case of

the Smith boys, the experience -- to steer the business into the future. And so everything was sold.

There was a sort of legacy, though. The electrical plant was the last substantial commercial enterprise

to operate in Martintown. Wisconsin Power & Light acquired ownership from the consortium, built a new

brick building in about 1930 to house a brand-new, up-to-date dynamo, and kept generating power there

for decades to come. In its final days, the on-site manager was Tinty’s grand nephew Frederick Cullen

“Fritz” Hastings.

Elwood resigned himself to spending his dwindling time as an invalid at his home, where he finally

expired 6 March 1930 of pneumonia and heart inflammation. His remains were interred at Rock Lily

Cemetery, Winslow. In the 1920s, he had decided he would not be buried with Tinty at the Martin

Cemetery. Instead, at some point in the last few years of his life, he had arranged for her casket

to be dug up and reburied at Rock Lily near the graves of Claude and Blanche. Her headstone

was left in place at Martin Cemetery, but her actual remains are no longer below it, and Elwood’s name

and stats were never carved on that stone, though in 1902 space had been left for that purpose.

E.B. and Tinty with their children Claude, Arley, Rose, and Blanche, early or

mid-1890s

Children of Mary Lincoln Martin

with Elwood Byron Bucher

Claude Earl

Bucher

Arletta Pearle

Bucher

Rose Marie

Bucher

Blanche B.

Bucher

Ralph Byron

Bucher

For genealogical details, click on

each of the names.

To return to the Martin/Strader Family main page, click here.

Mary Lincoln Martin, the eleventh of the fourteen children of

Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, was born 12 August 1863 in Martintown, Green County, WI. Obviously

named after the nation’s then-current First Lady, she was known to the family as Tinty. It is not known

how she obtained such an unusual nickname, which sometimes appears in family correspondence as Tintie

and Tinta, except that it might somehow have come from her middle name. How one gets “Tinty” from

“Lincoln” is a mystery, but the nickname was part of a set shared with her brother Abraham Lincoln

Martin, the set being Linky and Tinty. Perhaps Tinty evolved from an earlier version, Tinky being the

prime possibility.

Mary Lincoln Martin, the eleventh of the fourteen children of

Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, was born 12 August 1863 in Martintown, Green County, WI. Obviously

named after the nation’s then-current First Lady, she was known to the family as Tinty. It is not known

how she obtained such an unusual nickname, which sometimes appears in family correspondence as Tintie

and Tinta, except that it might somehow have come from her middle name. How one gets “Tinty” from

“Lincoln” is a mystery, but the nickname was part of a set shared with her brother Abraham Lincoln

Martin, the set being Linky and Tinty. Perhaps Tinty evolved from an earlier version, Tinky being the

prime possibility. Tinty (shown at right at about age seven) was one of

the youngest children of Nathaniel and Hannah, so it was only natural that her own children were among

Nathaniel and Hannah’s youngest grandchildren, and there are strong indications Hannah doted on them. The

matriarch had plenty of opportunity to do so because Tinty remained emotionally and geographically close

to her parents. Tinty and Elwood and their brood

dwelled first right in Martintown and then, some time in the 1890s, moved only a tiny bit south over

the state line to Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. (Shown below at right is their home a hundred

years after they moved into in it.) Tinty and Elwood had the five children whose biographies can

be found by clicking on their names at the bottom of this page, as well as a set of male twins, born

25 September 1890 in Martintown. No source provides a name for either of the twins, who were probably

born prematurely as twins often are. This lack of known names implies they died very early in their

infancies. However, it is believed they were not stillborn, or their existence would probably not

have been noted at all. Instead, they are referred to in family genealogical notes and in Elwood’s

obituary. The 1900 census plainly states that Tinty had given birth seven times and confirms that

two had died. Their birthdates were not recalled within the family, but by 1890, Green County was

beginning to make a practice of keeping birth records on file, and so the Wisconsin Birth Index was

used to determine when they came into the world. Whether either or both of the twins survived past

the 25th is not yet known.

Tinty (shown at right at about age seven) was one of

the youngest children of Nathaniel and Hannah, so it was only natural that her own children were among

Nathaniel and Hannah’s youngest grandchildren, and there are strong indications Hannah doted on them. The

matriarch had plenty of opportunity to do so because Tinty remained emotionally and geographically close

to her parents. Tinty and Elwood and their brood

dwelled first right in Martintown and then, some time in the 1890s, moved only a tiny bit south over

the state line to Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. (Shown below at right is their home a hundred

years after they moved into in it.) Tinty and Elwood had the five children whose biographies can

be found by clicking on their names at the bottom of this page, as well as a set of male twins, born

25 September 1890 in Martintown. No source provides a name for either of the twins, who were probably

born prematurely as twins often are. This lack of known names implies they died very early in their

infancies. However, it is believed they were not stillborn, or their existence would probably not

have been noted at all. Instead, they are referred to in family genealogical notes and in Elwood’s

obituary. The 1900 census plainly states that Tinty had given birth seven times and confirms that

two had died. Their birthdates were not recalled within the family, but by 1890, Green County was

beginning to make a practice of keeping birth records on file, and so the Wisconsin Birth Index was

used to determine when they came into the world. Whether either or both of the twins survived past

the 25th is not yet known. Tinty and then Horatio’s demise set the stage for their

surviving spouses, Elwood Bucher and Laura Hart Martin, to find solace from their loneliness in

each other. They would marry 21 March 1907 in Chicago, meaning that the children of Tinty and

Horatio would henceforth be not only first cousins, but step-siblings.

Tinty and then Horatio’s demise set the stage for their

surviving spouses, Elwood Bucher and Laura Hart Martin, to find solace from their loneliness in

each other. They would marry 21 March 1907 in Chicago, meaning that the children of Tinty and

Horatio would henceforth be not only first cousins, but step-siblings. Elwood embraced the new era, seeing new opportunities. At this

point, it was taken as

a given that electricity would soon be the standard way every American home would be lit. Electrical

appliances -- stoves, refrigerators, vacuums -- were poised to become equally common, if not quite

so soon. In Martintown and Winslow, there was as yet no electrical utility company. Elwood saw that

he could tap the power of the mills’ waterwheels and meet that demand. In 1909 he was awarded a

contract by the town of Winslow to supply enough electricity in the evenings for the street lights,

allowing the gas lights to be retired. By September of that year -- a month ahead of deadline -- he

delivered on his promise. The electric plant eventually became the mills’ prime reason to exist, ahead

of flour and lumber.

Elwood embraced the new era, seeing new opportunities. At this

point, it was taken as

a given that electricity would soon be the standard way every American home would be lit. Electrical

appliances -- stoves, refrigerators, vacuums -- were poised to become equally common, if not quite

so soon. In Martintown and Winslow, there was as yet no electrical utility company. Elwood saw that

he could tap the power of the mills’ waterwheels and meet that demand. In 1909 he was awarded a

contract by the town of Winslow to supply enough electricity in the evenings for the street lights,

allowing the gas lights to be retired. By September of that year -- a month ahead of deadline -- he

delivered on his promise. The electric plant eventually became the mills’ prime reason to exist, ahead

of flour and lumber. The good times lasted only about five years, then

Elwood’s doctor son Claude was killed by an automobile crash in late 1915 while making a house call. At

the end of 1918, Blanche succumbed to the great influenza epidemic. Both died in their early thirties.

About 1920, Elwood’s health failed. The precise nature of his malady is not well described in surviving

notes, but he was weak enough he sometimes resorted to a wheelchair (though he was capable of standing

upright, as shown in the photo at left, with Laura outside their home). Grandson Lyle Smith recalled

that as an adolescent he was not allowed to see Grandpa Elwood because he had some sort of “bad disease.”

This may have meant Elwood had a condition that was contagious or unsightly, tuberculosis being the

prime candidate, or it could mean he had something morally repugnant, such as syphillis. Much of his

care fell to his brother John, who moved into the Winslow home with Elwood, Laura, and their

“grown-sons-still-at-home” Fay and Ralph, Clark having moved to Washington state, where he worked at

the creamery of Elwood’s brother Charles Benedict Bucher. Whatever it was, it was chronic. Extended

forays to the South and the West, taken in hope of therapeutic benefit, did nothing to help.

The good times lasted only about five years, then

Elwood’s doctor son Claude was killed by an automobile crash in late 1915 while making a house call. At

the end of 1918, Blanche succumbed to the great influenza epidemic. Both died in their early thirties.

About 1920, Elwood’s health failed. The precise nature of his malady is not well described in surviving

notes, but he was weak enough he sometimes resorted to a wheelchair (though he was capable of standing

upright, as shown in the photo at left, with Laura outside their home). Grandson Lyle Smith recalled

that as an adolescent he was not allowed to see Grandpa Elwood because he had some sort of “bad disease.”

This may have meant Elwood had a condition that was contagious or unsightly, tuberculosis being the

prime candidate, or it could mean he had something morally repugnant, such as syphillis. Much of his

care fell to his brother John, who moved into the Winslow home with Elwood, Laura, and their

“grown-sons-still-at-home” Fay and Ralph, Clark having moved to Washington state, where he worked at

the creamery of Elwood’s brother Charles Benedict Bucher. Whatever it was, it was chronic. Extended

forays to the South and the West, taken in hope of therapeutic benefit, did nothing to help.