Eleanor Amelia “Nellie”

Martin

Eleanor Amelia Martin, along with her twin Alice Adelia

Martin, was born 11 May 1849 in Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. Within a year or so of her birth,

the family moved a mile or so north across the Wisconsin state line to the place along the Pecatonica

River where her father would found the village of Martin (to be renamed Martintown late in the 19th

Century). This would be her home for the rest of her childhood. She went to school within sight of

the family dwelling, at first in a twelve-foot square building with only her brothers Elias and Horatio

and sister Jennie and the neighboring Lockman children as classmates. The teacher in those early years

was Belle Bradford, daughter of John Bradford, a man who had once been her father’s employer.

Eleanor Amelia Martin, along with her twin Alice Adelia

Martin, was born 11 May 1849 in Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. Within a year or so of her birth,

the family moved a mile or so north across the Wisconsin state line to the place along the Pecatonica

River where her father would found the village of Martin (to be renamed Martintown late in the 19th

Century). This would be her home for the rest of her childhood. She went to school within sight of

the family dwelling, at first in a twelve-foot square building with only her brothers Elias and Horatio

and sister Jennie and the neighboring Lockman children as classmates. The teacher in those early years

was Belle Bradford, daughter of John Bradford, a man who had once been her father’s employer.

Nellie’s twin died at less than five months of age, but Nellie thrived. Aside from having an eye that

did not track the same as the other, she enjoyed good health and would ultimately survive more than

eighty years. In this she contrasted sharply with the majority of her siblings. Of all the fourteen

children of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader, only she and her brother Elias and sister Juliette

would live to be elderly. In her childhood, Nellie saw sibling after sibling die at less than three

years of age. Another challenge reared its head in the winter of 1857-58, when her father suffered a

nervous breakdown so severe his brother-in-law Jeremiah Frame was temporarily given power-of-attorney

over his legal affairs. As the eldest daughter, Nellie probably had to shoulder an unusual share of

household responsibility given how many younger children there were, and given the occasional

unsettled interval such as the 1857-58 turmoil. However, in general respects, Nellie’s childhood was

secure and even enviable. She was the daughter of the village patriarch and major landowner. Though

born at a point when many Stephenson County and Green County homes were still only log cabins or

something equally primitive, her environment as a whole grew more economically and socially robust

with each passing year.

As the eldest daughter of the wealthiest man in the

immediate vicinity, Nellie was quite a prize to be had as far as suitors were concerned. But Nellie

did not concern herself with her social position; she wanted a mate of good character over all else.

And so she accepted the attentions of John Warner of Winslow. John, born 24 February 1847, was the

son of John Warner and Marancy Alexander, both formerly of New York state, and among the region’s

pioneers. John Sr. and Marancy had wed in 1841 and established one of Winslow’s original

homesteads -- in fact, Winslow had not yet formally existed when the Warners had taken possession

of the parcel. John’s father had died before John had turned

eleven. He had for several years thereafter served as the head of the household, responsible for the

support of his older sister and three younger brothers, until his mother had remarried in 1862. Cast

into the workforce early, John had acquired a variety of skills. Among them was an understanding of

machinery and of mill equipment. (His father had been a sawmiller, and briefly a partner of John

Bradford.) His introduction to Nellie may well

have resulted from his job helping to maintain gristmill and sawmill equipment at the Martin mills.

Their relationship blossomed into a courtship and they were married 21 April 1869. As was often the

case of marriages between Martintown or Winslow residents, the couple ventured up to Monroe, the

seat of Green County, to take care of the bureaucratic aspects. The rites there were conducted by

Justice of the Peace S.W. Abbott and witnessed by a pair of Monroe residents, M.J. Gardner and Mary

Reynolds. Neither of those women appear to have been individuals who knew John and Nellie well, and

S.W. Abbott himself had no direct connection -- they were just the people available on the spur of

the moment. The “real” wedding was held in Martintown in front of the full gaggle of kinfolk and

friends.

As the eldest daughter of the wealthiest man in the

immediate vicinity, Nellie was quite a prize to be had as far as suitors were concerned. But Nellie

did not concern herself with her social position; she wanted a mate of good character over all else.

And so she accepted the attentions of John Warner of Winslow. John, born 24 February 1847, was the

son of John Warner and Marancy Alexander, both formerly of New York state, and among the region’s

pioneers. John Sr. and Marancy had wed in 1841 and established one of Winslow’s original

homesteads -- in fact, Winslow had not yet formally existed when the Warners had taken possession

of the parcel. John’s father had died before John had turned

eleven. He had for several years thereafter served as the head of the household, responsible for the

support of his older sister and three younger brothers, until his mother had remarried in 1862. Cast

into the workforce early, John had acquired a variety of skills. Among them was an understanding of

machinery and of mill equipment. (His father had been a sawmiller, and briefly a partner of John

Bradford.) His introduction to Nellie may well

have resulted from his job helping to maintain gristmill and sawmill equipment at the Martin mills.

Their relationship blossomed into a courtship and they were married 21 April 1869. As was often the

case of marriages between Martintown or Winslow residents, the couple ventured up to Monroe, the

seat of Green County, to take care of the bureaucratic aspects. The rites there were conducted by

Justice of the Peace S.W. Abbott and witnessed by a pair of Monroe residents, M.J. Gardner and Mary

Reynolds. Neither of those women appear to have been individuals who knew John and Nellie well, and

S.W. Abbott himself had no direct connection -- they were just the people available on the spur of

the moment. The “real” wedding was held in Martintown in front of the full gaggle of kinfolk and

friends.

(This website contains a section devoted to the Warner family. To read a biography specifically

centered on John, click here)

Nellie and John stayed in Martintown for the next three decades aside from a brief interval in the

1880s. This was in sharp contrast to John’s siblings, who over the course of the 1870s would all head

off to new homesteading

opportunities in Nebraska, taking Marancy (a widow again) with them. John enjoyed a local advantage his

kin did not. Nathaniel Martin owned so much land that he was able to give each of his children eighty

acres upon their marriages. Nellie’s dowry consisted of a parcel that lay along

the northern bank of the Pecatonica opposite the main part of the village. Six of the couple’s eight

children were born there. The exceptions were first son John Martin Warner, born in Winslow in 1870,

and seventh child Albert Frederick Warner, born in Willow Springs, Howell County, MO during the summer

of 1884. (Nellie and family accompanied her sister Emma Brown and family when the Browns were based in

Howell County for a period in the mid-1880s, where Cullen Brown was a lumber merchant and probably

operated or helped operate a sawmill. The Warners were gone from Martintown for only a year or so.)

The births occurred every other year from 1870 to 1886, with the exception of 1880. (Nellie had a

miscarriage that year.) Ida Ellen, the fifth child, would succumb to diphtheria at only a year and a

half of age and would be buried in the Martin family cemetery on the hill above Martintown, becoming

the second grandchild of Nathaniel and Hannah Martin to be laid to rest there, only three months after

her first cousin and playmate Edna Brown had passed away. (Ida Ellen and Edna had both been born in

August, 1878.)

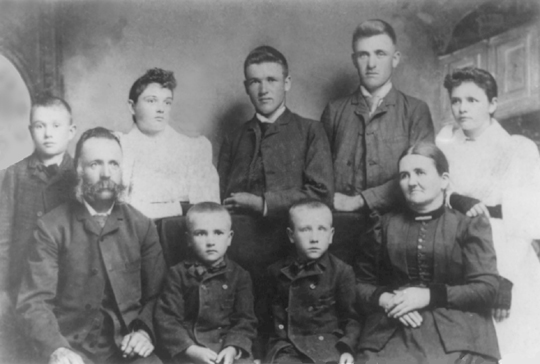

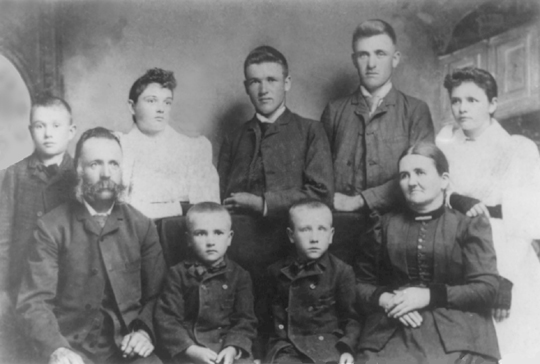

Taken in the early 1890s, this formal portrait shows the entire family of John Warner

and Nellie Martin, with the exception of Ida Ellen Warner, who had perished more than a decade

earlier. John is seated at left, Nellie on the right, with youngest sons Walter (l) and Bert (r)

seated between them. Standing in the back are, left to right, Cullen, Cora Belle, Charles, John,

and Emma.

Though the farm provided a certain amount of security, John did not particularly view himself as a

farmer, even though farming took up quite a bit of his time. He saw himself as a businessman. He was

undoubtedly one of his father-in-law’s right-hand men, but made

sure to establish his own direct and independent sources of income. And a good thing, because he had a

large family to support. Sometimes a few mouths extra, as in the late 1870s and early 1880s when he

and Nellie took in Nellie’s teenaged cousins Henry Seward Martin and Isaiah Elias Martin, sons of her

uncle Charles Alexander Martin. (Charles and his wife had separated.) During the 1890s, John’s ways of

generating income varied even to the point of him becoming a county justice of the peace and an insurance

agent. He was also a small-scale investor, such as when he provided the capital for his elder sons to

purchase a large steam

tractor, who then proceeded to hire out themselves and the tractor to local farmers at harvest time

as the Warner Brothers. Most of all, John was a sawmill man, particularly when it came to the sales side

of the industry. He teamed up with local sawyer (and brother-in-law of his first cousin Harvey Mack)

Dayton D. Tyler as Tyler & Warner, producing custom hardwood lumber on Dayton’s farm a mile north of

Martintown. John’s success as a lumber broker eventually led to an opportunity at a distance. (This had

happened once before, leading to the sojourn in Howell County, MO.) John became associated with the

large Meyer Brothers’ lumber operation in Scioto Mills, ten miles southeast of Martintown. He seems to

have helped bring in business for them, perhaps directly and certainly as part of a new partnership,

Warner & Son, with secondborn son Charles Elias Warner. In order to take this job, he and Nellie moved to

Scioto Mills in the second half of the year 1900. Three of their older children, John, Emma, and Belle,

were married and living independent lives by then, but their four younger sons came with them to Scioto

Mills.

The relocation to Scioto Mills represented a watershed moment in the destiny of the immediate family. Finally the

tight connection with Martintown and Winslow became weakened in a lasting way. The Warners would only reside

for six years in Scioto Mills, but it was there that developments occurred that erased any prospect of

coming back to their old haunts. It was a health crisis that locked in the course-change for good. Son

Cullen began a romance with a young lady, Minnie Brecklin -- quite possibly a first cousin of Nellie and

John’s daughter-in-law Anna Lueck, wife of John Martin Warner. This led to a marriage

in 1903 and in May of 1904, the birth of Selma Warner, the sixth of John and Nellie’s grandchildren. Soon

after the birth, Minnie manifested symptoms of tuberculosis. Cullen was soon ill as well. Nellie and John

had always been nurturant parents and had kept their children close even as adults. Charley still lived

at home and even their married offspring were not far away -- John Martin Warner was the proprietor of a

general store in Martintown and Emma and Belle and their husbands lived on Green County farms within

a mile of the village. Nellie and John immediately began to make plans and adjustments to alleviate the

situation their stricken son and daughter-in-law had found themselves in. Most important, they took over

care of Selma. (Shown at right is the Scioto Mills house.)

Minnie rapidly worsened. She died at the beginning of 1906. At

that point, Cullen’s doctor recommended he

be taken to a region with an arid climate to slow down the course of his own infection. The physician may

also have made it clear that the measure would help prevent other family members from contracting the

disease. Nellie and John’s response was profound. Despite the deep roots in southern Wisconsin and northern

Illinois, they accepted that the humidity and the cold winters were not what Cullen should be asked to put

up with any longer. Several of Nellie’s first cousins had settled in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

These cousins included her aunt Elizabeth Strader’s sons Elias Frame, William Patterson Frame, and Jacob

Silas Frame. The dry heat sounded like it was “just what the doctor ordered” and the Frames

recommended the area for other reasons. So Nellie and John headed off to Fresno County in December, 1906.

Minnie rapidly worsened. She died at the beginning of 1906. At

that point, Cullen’s doctor recommended he

be taken to a region with an arid climate to slow down the course of his own infection. The physician may

also have made it clear that the measure would help prevent other family members from contracting the

disease. Nellie and John’s response was profound. Despite the deep roots in southern Wisconsin and northern

Illinois, they accepted that the humidity and the cold winters were not what Cullen should be asked to put

up with any longer. Several of Nellie’s first cousins had settled in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

These cousins included her aunt Elizabeth Strader’s sons Elias Frame, William Patterson Frame, and Jacob

Silas Frame. The dry heat sounded like it was “just what the doctor ordered” and the Frames

recommended the area for other reasons. So Nellie and John headed off to Fresno County in December, 1906.

In the early part of the month, furniture and major household items, as well as the family horses and

their carriage, were loaded onto a freight car at Scioto Mills. Son Bert, then twenty-two years old,

rode in and kept watch over that car and its contents during its entire three-week journey west.

He was accompanied by Nellie’s sixteen-year-old nephew Fay Horatio Martin. The rest of the family lingered

to take care of one last important matter. Youngest son Walter Clare Warner refused to leave without his

sweetheart, Margaret Bell. The pair were married on Wednesday, the 12th. On Saturday the 15th, the family

boarded a passenger train. The group consisted of Nellie, John, Cullen, Selma, and the two newlyweds.

(Charley remained in Scioto Mills.) Because passenger trains had priority claim to the tracks and theirs

succeeded in maintaining a steady pace, this larger group of family members arrived well ahead of Bert and

Fay despite the lead the young men had built up.

Will Frame welcomed the Warners temporarily at his home in southern Fresno County near the small town of

Fowler. Of all the local relatives, Will and his brother Jake were the ones who particularly helped Nellie

and John get established in the county over the next few years. Will and Jake

were also in a position to recommend what sort of real estate the Warners might like now that they were

Californians. If so, John appears to have ignored their advice. He simply couldn’t suppress his tendency

to seek out not just a bargain, but an investment. He chose to purchase a substantial parcel along

the foothills of the Sierra Nevada east of the town of Clovis. The sale price was low. John assumed

this was because that part of Fresno County was not yet developed. The reality was that it was marginal

land, being neither out in the valley in proximity to an irrigation canal, nor up in the mountains with

timber that could be harvested, nor along any route whose commerce would generate economic opportunities.

But in 1907, the family was optimistic, and viewed the acreage as having the potential to be what the

Martintown farm had been for so many years -- a true family estate, one that would possibly pass down

through the generations.

This is not to say that the purchase was an outright blunder. John just didn’t take into account how much

California agriculture differed from that of Wisconsin and Illinois. To his credit, he recognized even

before handing over payment for the deed that his ranch would not have enough water to support crops. He

correctly saw that what he had was pasture. Accordingly, he soon acquired cattle to raise as stock. Bert

was his main assistant in this, with Cullen helping out whenever he was

feeling healthy enough. However, John kept expecting the soil to support a degree of grazing more like what

he was used to. It took a few seasons for him to understand just how much less grass grows when there are

no summer rains whatsoever. To support the numbers of animals he had acquired, he had to lease grazing

rights on other property, and bring in supplemental hay. With each additional expense, his expected profit

shrank.

The nearest post office was at the tiny trading post of

Academy, so inevitably when the family wrote home,

or were being written to, the address was simply “Academy.” Their name for their property was Spring Brook

Ranch, but this did not stick. When spoken of in later years, it was nearly always called “the Fancher

Creek place,” the name taken from the seasonal stream that ran through the parcel. A house was quickly built

to match the scale of the ample residence the family had enjoyed in Scioto Mills. (Shown left, the Fancher

Creek place and its main house.)

The nearest post office was at the tiny trading post of

Academy, so inevitably when the family wrote home,

or were being written to, the address was simply “Academy.” Their name for their property was Spring Brook

Ranch, but this did not stick. When spoken of in later years, it was nearly always called “the Fancher

Creek place,” the name taken from the seasonal stream that ran through the parcel. A house was quickly built

to match the scale of the ample residence the family had enjoyed in Scioto Mills. (Shown left, the Fancher

Creek place and its main house.)

John and Nellie were committed to California from the start, as were Cullen, Bert, and Selma. Walter and

Margaret did return to Scioto Mills for the summer of 1907, but after toying with the idea of staying there,

made up their minds and came back west for good. With that, the tide turned. Eventually all of John and

Nellie’s offspring came to Fresno County. This is evidence of the sort of person Nellie was. She had

been -- and still was -- such a good mother that her children didn’t want to be widely separated from her.

Even during the stretch from 1907 to 1910, though Charley, Belle, and Emma were in theory still residents

of either Martintown or Scioto Mills, they were with their mom and dad on extended visits lasting anywhere

from six weeks to four months of each calendar year -- despite the ordeal of long train trips.

The ranch was quite a ways from any true settlement. This was convenient in the sense that it kept Cullen

from rubbing elbows with neighbors who might worry about his tuberculosis. But the isolation did not appeal

to Nellie, who on a typical day had no female company other than her young granddaughter. John didn’t care

for the logistics, either. He enjoyed wheeling and dealing. Being a cattleman left him unfulfilled. He was

competent enough at it, but not as good as neighbors who had devoted far more years to that means of making

a living. So John began spending more and more time in the nearest towns -- Clovis and Fresno among them.

Another place was Sanger, ten miles due south of the ranch. Sanger was a small town, but had a solid economic

base because it was located at the terminus of one of the flumes that carried logs down from the Sierra Nevada

to be turned into lumber, which would then be shipped off to customers by rail, Sanger being situated right on

a Southern Pacific Railroad line. John was a sawmiller. Sanger was a sawmill town. John was a merchant, and

Sanger had commerce. So he kept his eye out for business opportunities there. He and Nellie and little Selma

may even have been in the habit of spending two or three days at a time there, getting rooms in a favorite

hotel rather than having to make the lengthy wagon ride there in the morning and then cover those same miles

home by evening.

Given how settled Nellie’s first fifty years of life had been, it must have been a challenge over the first

couple of years in California for her to adjust to her new circumstances. It was so different from what she

knew. When the family had gone to

Missouri, she had known the relocation was temporary and had had the company of her sister Emma. While

in Scioto Mills, she had been able to make day trips back home. But now she was far from old friends

and familiar settings. It helped that she had some of her children nearby, and she no doubt appreciated

the opportunity to get to know her Frame cousins again. Due to their moves to Iowa, Nebraska, Colorado,

and California, she had seen little of them since her twenties.

Nellie’s focus was largely upon Selma. She had been the mother

of eight, and now she was a mother one last time. As a man of his era, Cullen would not have been involved in

a lot of direct childcare even if he had been healthy, but that was even more the case given his potential

contagiousness. (At right, Nellie with Selma in about 1910.) It meant a great deal to Cullen to have his

daughter around, though, and Nellie was consoled that at least she could do that much for her ailing boy.

Nellie’s focus was largely upon Selma. She had been the mother

of eight, and now she was a mother one last time. As a man of his era, Cullen would not have been involved in

a lot of direct childcare even if he had been healthy, but that was even more the case given his potential

contagiousness. (At right, Nellie with Selma in about 1910.) It meant a great deal to Cullen to have his

daughter around, though, and Nellie was consoled that at least she could do that much for her ailing boy.

Walter and Margaret Warner officially lived at Spring Brook Ranch until the early part of 1909. They occupied

a small shack separate from the main house. They were often gone, though. They made a habit of accompanying the

Frame cousins up and down the Central Valley as migrant farmworkers, earning money picking oranges, grapes, and

peaches, among other crops. Charley Warner did this as well during intervals when he was not in Scioto Mills.

Belle and Alie Spece arrived in the early part of 1909. Their intention had been to stay in Green County,

where Alie for three years had been adapting the infrastructure of his farm in order to open a cheese factory.

No sooner did he finally get the factory going than it seemed Belle was coming down with TB. A relocation to

California was

hastily arranged. Thankfully Belle did not develop the disease, but it would take a while to be sure she had

been spared. In the meantime, the relocation was a done deal. Belle and Alie soon established themselves in

Sanger. It was only the first of a series of major family events that took place in the early months of

that year, some good, some bad. One of the good developments was that John and Nellie decided to buy twenty

acres of farmland down in the Fowler/Del Rey area near Will Frame’s place. The price for land was

extraordinarily low at that point and John wanted to take advantage. Their plan was for Walter and

Margaret to develop this acreage, with the understanding that if the young couple stuck it out for the

long haul, they would be able to use some of the money they earned from their harvests to acquire the title

deed from John and Nellie -- or perhaps receive it as a bequest. The worst of the bad developments was that

at last, Cullen’s case of tuberculosis got the

better of him. The doctor seems to have been right about the arid climate helping Cullen, but the positive

effect only lasted a couple of years. By the spring of 1909, it became obvious that the end was imminent.

In late April the family gathered for the death vigil at the Fancher Creek house. The group included

not only the immediate Warner family, but some of the Frame cousins as well. Cullen passed away after

much suffering 1 May 1909. The next day the family gathered again for the sad task of digging his

grave at the Academy cemetery. Jake Frame, who was a minister, conducted the rites.

Nellie and John had not managed to develop a true fondness for Spring Brook Ranch, and now that the place was

associated with Cullen’s awful death, any residual enthusiasm they had for the property dribbled away. They

still used it as their official base for another fourteen months, but spent more and more time away from it.

This became particularly true in early 1910 with the arrival in Fresno County of son John, daughter-in-law

Anna, and grandchildren Leslie and Dorothy. Anna Lueck Warner had tuberculosis. As with Cullen, it was hoped

that the arid climate would help her. This was no small move. John had been doing well as owner of Martintown’s

general store. The couple are unlikely to have relocated if not for the health crisis. Coming with them was

Charley Warner, who would now stay year-round in California, and though he spoke occasionally of going back to

Scioto Mills, did not actually do so until the 1940s as an elderly man.

With so many Warner men on-hand, an assortment of money-making prospects were discussed and attempts made in

order to “test the waters.” For a number of months during the early part of 1910, John M., Charley, and Walter

operated a produce stand in downtown Fresno near the railroad tracks. This area, though it was probably only

a square mile or so in total area, was the mercantile hub of Fresno County. It may have been Jake Frame who

lured them there. In 1909, Jake and his immediate family had become based in Fresno in a big way, and this

would continue to be the situation for years to come. Jake was the sort of person who would have been eager to

have plenty of extended family members get in on the spiritual and moral life of the community there. However, as

far as the earning potential of the produce stand went, it may have been too much a case of

the old adage, “Location. Location. Location.” In other words, there were so many competitors the Warners soon

came to see they might do better in a commercially less-exploited spot. Soon plans were being revised.

Meanwhile, John Sr. and Nellie proceeded in a methodical fashion to divest themselves of the ranch. They had

not instantly sold it after Cullen’s death, a prime reason being that they couldn’t absorb the financial hit

if they simply took the first offer and then hurried away. They needed to get their cattle fully raised and

fattened, and pick the proper juncture to sell them. In contemplating that prospect, John in his

typical entrepreneurial flair realized he didn’t need to sell out to a feed lot or slaughterhouse or to another

rancher. He was quite at ease dealing with customers, so why not rent a storefront for half a year, open a

butcher shop, and sell the beef at retail? And so he did just that. In the early summer of 1910, he found

suitable quarters in Fresno near his sons’ fruit-and-vegetable outlet. It is true that John did not have any

previous experience as a butcher shop proprietor, but he apparently was not intimidated to plunge right in.

Perhaps he had written to his nephew John Warner Ladd, who had been operating a meat market in Creighton,

Knox County, NE for half-a-dozen years, and would have been able to provide his uncle with plenty of tips as

to how to best proceed with the venture.

John wrapped up his brief butcher shop phase by the end of calendar year 1910. By then the ranch was no

longer needed to keep the cattle. The deed was traded for shares of mining stock. Having no more need to

stay in Fresno, Nellie and John moved themselves into the house on the twenty-acre Del Rey farm they

had purchased for Walter and Margaret. The younger couple had decided not to commit themselves to it. Walter

had farmed it in 1909 and probably put in hours managing it through the 1910 harvest, but he and Margaret and

their baby boy Clare had not actually lived there for quite some time, preferring to be in Fresno where

Walter could more easily attend to Warner Brothers Produce. Back in the early Twentieth Century, in the

absence of air-conditioning, such businesses as produce outlets typically opened by six or seven in the

morning to take advantage of cool morning temperatures, and a commute up from Del Rey (probably by train)

each day would not have been practical. By this point, the farm house was the only house that Nellie and

John actually owned. They decided to stay there -- thereby avoiding having to pay rent -- until they

figured out where to go next.

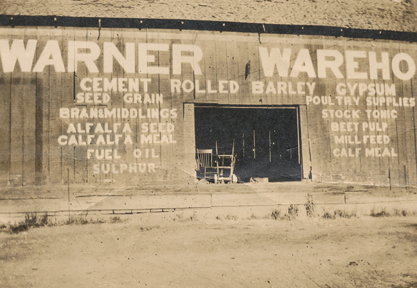

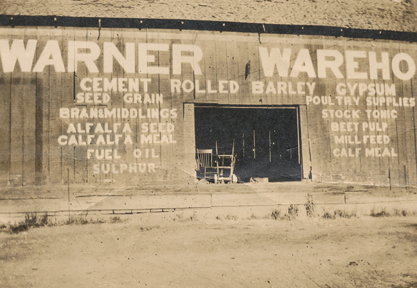

The answer to the question -- “Where to go next?” -- quickly became an easy one to answer. John M. Warner

decided he liked the potential of Sanger as a place of business. In a case of “thinking big,” he convinced

his father to put up half the funds and open up a warehouse in Sanger to sell feed grain and hay and

livestock-related hardware, as well selling as the sort of bulky items that require a warehouse to properly

cope with, such as cement, gypsum, and sacks of flour. Sanger already had an existing operation of that sort,

Farmers Warehouse. The two Johns, father and son, bought out the owners and expanded the operation and the

physical structure to a scale never before seen in the community. Among other things, that meant they could

earn some of their income without even having to handle merchandise -- they simply rented otherwise empty

portions of the building to clients who needed to store their own large equipment and/or wholesale supplies.

The increase in the square footage was so significant that local historians of the 1970s would treat the

juncture as the moment when Sanger acquired its first truly urban structure and became more than just a

village. Indeed, its founding was one of the spurs that led to the incorporation of the town less than a

year later. The new business was called Warner Warehouse Company. The name was painted in huge letters on

the side of the building, as can be seen in the photo shown slightly below at left.

The elder John, though excited by the enterprise and

certainly a big part of the planning and organization, was growing rickety enough that he was content to

supervise rather than commit to on-the-clock shifts as a warehouseman, nor was he even on-site every day.

That meant that right away, an additional

manager was needed to help John Martin Warner on the floor. Bert was hired to do that. His salary was sixty

dollars per month. This was generous enough that he knew he could support a wife, and soon have enough to buy

himself and that wife a house, so he and his sweetheart Grace Branson, a teacher at Round Mountain School in

the hills east of Spring Brook Ranch, set in motion their wedding plans. Meanwhile Alie Spece got in on the

income-earning potential by opening up a feed lot right next to the warehouse. Cattlemen of the hills were

in the habit of bringing stock down to Sanger to load them onto trains to go to market. The combination of

grain warehouse and feed lot right by the railroad tracks ensured Alie would have customers.

The elder John, though excited by the enterprise and

certainly a big part of the planning and organization, was growing rickety enough that he was content to

supervise rather than commit to on-the-clock shifts as a warehouseman, nor was he even on-site every day.

That meant that right away, an additional

manager was needed to help John Martin Warner on the floor. Bert was hired to do that. His salary was sixty

dollars per month. This was generous enough that he knew he could support a wife, and soon have enough to buy

himself and that wife a house, so he and his sweetheart Grace Branson, a teacher at Round Mountain School in

the hills east of Spring Brook Ranch, set in motion their wedding plans. Meanwhile Alie Spece got in on the

income-earning potential by opening up a feed lot right next to the warehouse. Cattlemen of the hills were

in the habit of bringing stock down to Sanger to load them onto trains to go to market. The combination of

grain warehouse and feed lot right by the railroad tracks ensured Alie would have customers.

The new businesses and the wedding plans made the early part of the year 1911 a seemingly propitious time for

the Warner clan. There was however a fly in the ointment. Anna Lueck Warner’s tuberculosis progressed

rapidly. She went back to Green County so that she could die amongst Lueck family members. She passed away

7 May 1911. Naturally her decline, her death, and the logistics of childcare arrangements for Leslie and

Dorothy claimed John M. Warner’s attention, and he could not devote himself to Warner Warehouse Company to the

degree he had hoped. Charley helped fill his shifts, as he had once done at the Martintown general store.

Alie helped out as well, and in return, Charley and Bert helped at the feed lot. It was very much an all-family

circle of support.

In 1912 and 1913, the changes were nearly as rapid. As a new widower, John M. found he did not have the heart

to soldier on with his grand venture, though he did choose to remain Out West rather than writing off the whole

California sojourn as a mistake and beating a permanent retreat back to Martintown. Meanwhile John, Sr. came

to accept that his health and vigor were dwindling, and that had no choice but to scale back his activity level.

Accordingly, both Johns sold their shares in Warner Warehouse Company. Bert and Alie became the new owners and

proprietors, Alie having come to regard the feed lot to be a marginal business, and having briefly, for the

1913 harvest season, having farmed peaches near Del Rey. The partnership between Bert and Alie would last

for the next six years.

Nellie and John -- still with granddaughter Selma as part of their household -- continued to reside in

Sanger even after the transfer of warehouse ownership. John did enjoy investigating investment opportunities,

though. While Walter was working in the Sierra Nevada in the mid-1910s, John visited sawmills, inspected

standing timber, or even just took in the sights in those high elevations of the state. After all, he had

never seen real mountains until he had moved to California, and to be among those peaks and granite

faces was still awe-inspiring. It was on one of his forays that he had a stroke and/or heart attack and died

on the third of January, 1916.

Nellie was a widow at sixty-six. She never gave a moment’s thought to remarriage. With young Selma still her

dependent, Nellie moved in with Charley. Charley had always been the one of her children she was most attached

to, and vice versa. Though Nellie had some money in the bank and now started to receive a Civil War widow’s

pension, she probably would have found it hard to get by if she’d had to pay all of the expenses of her

own home. The pension, for example, was only fifteen dollars a month when John died, rising to eighteen

24 February 1917 on what would have been his seventieth birthday. Even in the late 1920s during Nellie’s

final years of life, the benefit was a modest forty dollars a month. Charley was at that time a Fresno

County farmer, though the home he was renting was fully within the city limits of Sanger. Or at least it

seems so. Nellie and her son and granddaughter are enumerated in Sanger in the 1920 census; it remains

possible they had only recently moved there and had spent the previous few years on the acreage Charley

had been cultivating.

In 1918 daughter Mary Emma Warner and her husband Fred Hastings and their three children finally made the

move from Wisconsin to Sanger. It was yet another testament to Nellie’s nurturant qualities that even her

eldest daughter wanted to be around her over forty years after she had been a baby. Not long after Emma’s

arrival, probably in 1919 when Bert bought out Alie and became sole owner of Warner Warehouse Company,

adding a gas station to the operation, Charley stopped farming and resumed putting in hours at the warehouse,

leaving Bert free to concentrate on the station -- that is to say, the new-fangled part of the business.

(One of Bert’s early steps was to hire his brother-in-law Fred to work at the station.) If Charley and

Nellie and Selma had been living in a rural situation until then, 1919 was the point when they moved into

Sanger.

(Shown at right is

Nellie in the late summer of 1918 in an image from Emma’s collection, preserved by Emma’s heirs. This photo

was undoubtedly taken to commemorate Emma’s arrival; the occasion must have been the first time in

a dozen years that Emma had been able to pose for a group shot with so many of her siblings. The teenage

girl on the far left may be Selma but is more likely to be Erma Alice Spece. On the far right, the young

woman is Gladys Beryl Spece. The middle-aged individuals in this image are Nellie’s four eldest children.

In the back is Charles Elias Warner. From left to right in front are Mary Emma Warner Hastings, John Martin

Warner, and Cora Belle Warner Spece.)

(Shown at right is

Nellie in the late summer of 1918 in an image from Emma’s collection, preserved by Emma’s heirs. This photo

was undoubtedly taken to commemorate Emma’s arrival; the occasion must have been the first time in

a dozen years that Emma had been able to pose for a group shot with so many of her siblings. The teenage

girl on the far left may be Selma but is more likely to be Erma Alice Spece. On the far right, the young

woman is Gladys Beryl Spece. The middle-aged individuals in this image are Nellie’s four eldest children.

In the back is Charles Elias Warner. From left to right in front are Mary Emma Warner Hastings, John Martin

Warner, and Cora Belle Warner Spece.)

Nellie’s role as a foster mother was cut a bit short. Selma was just shy of her sixteenth birthday when

she wed William Robert Mead in the spring of 1920. Nellie and Charley became a two-person household, and

did not need a house as large as the one they had been renting. They soon moved a fraction of a mile to

1811 Palm Avenue, putting them within a minute’s stroll of the homes of Emma, Belle, and Walter and their

families, who one way or another had all ended up congregating around a block defined by Hoag Avenue,

Palm Avenue, De Witt Avenue, and Tenth Street. Nellie therefore became almost as immediate a presence in

the lives of the majority of her surviving children as she had been in her forties, with four of the six

so very close at hand and Bert only a mile away. John was the exception, choosing at this juncture to move

to Yucaipa, San Bernadino County, CA to attempt to become an apple farmer. Alas, the togetherness was

disrupted in a fashion that could be described as “not the way Warners usually behave.” Walter apparently

said something Bert could not forgive. None of those who were there at the time preserved what was said, so

the particulars are

unavailable today, but the impression is, Walter -- perhaps while drunk -- disparaged Grace Branson Warner

in some way. Bert never spoke to Walter again. The rift was so long-lasting and profound that when Walter

died in 1946, Bert was not told until it was too late for him to attend the funeral. Everyone assumed

(incorrectly) that Bert wouldn’t want to attend. By the mid-1920s, not one of Nellie’s kids were still

residing in the tight enclave. Emma and Fred moved to Fresno, Fred giving up the job at the service station.

Walter and Margaret moved to Santa Cruz. Belle and Alie moved to a peach farm near Del Rey -- perhaps to the

very same acreage they had occupied in 1913. And Charley and

Nellie moved as well. In decades to come, the surviving family members would treat the matter as “in the

past,” but Nellie didn’t have that option. Not enough time. She would die while the schism was still freshly

ripped and still causing pain. She must have viewed the whole matter as the worst thing in the world that

could have happened, short of one of her children dying.

(At left, Nellie poses with her first cousin Jake Frame.

The setting is probably the farm of Jake’s son William Washington Frame near Conejo in southern Fresno

County. The apparent ages of the pair make it clear the photo was taken in the 1920s.)

(At left, Nellie poses with her first cousin Jake Frame.

The setting is probably the farm of Jake’s son William Washington Frame near Conejo in southern Fresno

County. The apparent ages of the pair make it clear the photo was taken in the 1920s.)

Nellie and Charley’s departure from Sanger may or may not have been influenced by the argument between

Bert and Walter. They may well have moved simply because doing so allowed Charley to take advantage of an

opportunity. In the latter 1910s he had been in effect stuck in place because moving would have meant

pulling Selma away from her classmates, something Charley would never have been so heartless as to do. But

now he could move if he wanted to. When John M. Warner decided he didn’t want to keep farming apples in

Yucaipa, he offered Charley the chance to step into his place, and Charley took him up on it. Nellie went

along. She did so even though this meant entering an existence bereft of almost all family members. She

had never had to deal with that sort of isolation before. We have Nellie’s own words to provide a glimpse

of her emotional state. The following is the full text of a birthday note Nellie wrote 2 June 1924 and

sent to Barbara Ann Spece Hastings. (Ann, born less than a month after Nellie and only a mile or so away,

was not only a beloved lifelong friend, but was the mother of Nellie’s son-in-law Fred Philo Hastings and

nephew-in-law Frank Opal Hastings.)

“Dear Old Friend: You did not answer my last letter but I will write you a birthday letter just the

same. I wish you a happy birthday and many more of them. I suppose that your son Hugh has got home by

this time as I heard that he left Fresno some time ago. He looks so much like his father, don’t you

think so? Charlie is like his father, too. Of course you know that I am down here with him. I like it

here very much only it is lonesome when Charlie is away and I have to stay alone nights. He is away

now but I expect him home today. I have stayed alone two nights. He has not sold all of his apples yet.

We have had quite a hard time to sell them on account of the quarantine for the hoof and mouth disease.

They have let up a little now. It sure has been hard on the farmers. I have not been so well since the

sick spell I had almost two years ago, but don’t get much thinner. Oh, how I wish you would come out

here and make a long visit. Wouldn’t there be some talking done. And ain’t you tired of boarding the

schoolmoms? Come out and take a rest. I think you have earned a good long one. Elma came down with us

the last time we were in Sanger and stayed four weeks less one day, then the rest of the family came

after her. Charlie said he wanted her to stay all summer. So did I. I suppose she has written and

told you about her visit up in Oregon where Selma, Cullen’s girl, is. And Aunt Maud and Uncle Joe were

there to see them. Well, I will say good bye. Love and kind thoughts from your friend. -- Nellie Warner.

P.S.: Write and tell me all about the old friends. I never expect to see any of them in this world,

but hope to meet all the loved ones in the better land when we are done with this.”

The Yucaipa phase took up most of the remainder of Nellie’s old age, but not quite all. The crop

quarantine of 1924 mentioned in the letter was only one struggle amid many that Charley faced as an

apple farmer, and in the latter half of the decade, he threw in the towel and returned to Fresno County.

Nellie of course came with him. She may or may not have been a member of his household once they got

there. The arrangement since 1916 had been that she was his cook and housekeeper. But Nellie was getting

so old she needed to scale back and let others take care of her. Charley had always been great with the

breadwinning aspects of supporting his mother, but now it was time to put her in the direct care of her

female relatives. Belle assumed the primary responsibility, which means that Nellie spent the majority

of her time with Belle and Alie on their peach farm near Del Rey. That was where she passed away 21

February 1930.

Nellie’s grave, shared with John, is located at Mendocino Avenue Cemetery, Parlier, CA, directly south

of Sanger. It can be found between the grave of grandson Elbert Clare Warner, who died at age four in

1913, and the grave of son Bert and his wife Grace. The headstone incorrectly lists Nellie as “Ellen

A.” Warner. She had been known as Nellie for so long that apparently her family members couldn’t recall

her formal name well enough when the stonecutter asked.

Here is Nellie as she looked less than a year before her death. This photograph was taken 9

May 1929 in the garden of the home of granddaughter Beryl at 707 West Avenue in Sanger. It is a

four-generations array consisting of Nellie, daughter Cora Belle Warner Spece, granddaughter

Gladys Beryl Spece Carter, and great-granddaughter Lillian LaVerne Johnston (daughter of Beryl’s sister

Erma Alice Spece Johnston).

Children of Eleanor Amelia “Nellie” Martin

with John Warner

John Martin

Warner

Charles Elias

Warner

Mary Emma

Warner

Cora Belle

Warner

Ida Ellen

Warner

Cullen Clifford

Warner

Albert Frederick

Warner

Walter Clare

Warner

For genealogical details, click on

each of the names.

To return to the Martin/Strader Family main page, click here.

Eleanor Amelia Martin, along with her twin Alice Adelia

Martin, was born 11 May 1849 in Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. Within a year or so of her birth,

the family moved a mile or so north across the Wisconsin state line to the place along the Pecatonica

River where her father would found the village of Martin (to be renamed Martintown late in the 19th

Century). This would be her home for the rest of her childhood. She went to school within sight of

the family dwelling, at first in a twelve-foot square building with only her brothers Elias and Horatio

and sister Jennie and the neighboring Lockman children as classmates. The teacher in those early years

was Belle Bradford, daughter of John Bradford, a man who had once been her father’s employer.

Eleanor Amelia Martin, along with her twin Alice Adelia

Martin, was born 11 May 1849 in Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. Within a year or so of her birth,

the family moved a mile or so north across the Wisconsin state line to the place along the Pecatonica

River where her father would found the village of Martin (to be renamed Martintown late in the 19th

Century). This would be her home for the rest of her childhood. She went to school within sight of

the family dwelling, at first in a twelve-foot square building with only her brothers Elias and Horatio

and sister Jennie and the neighboring Lockman children as classmates. The teacher in those early years

was Belle Bradford, daughter of John Bradford, a man who had once been her father’s employer. As the eldest daughter of the wealthiest man in the

immediate vicinity, Nellie was quite a prize to be had as far as suitors were concerned. But Nellie

did not concern herself with her social position; she wanted a mate of good character over all else.

And so she accepted the attentions of John Warner of Winslow. John, born 24 February 1847, was the

son of John Warner and Marancy Alexander, both formerly of New York state, and among the region’s

pioneers. John Sr. and Marancy had wed in 1841 and established one of Winslow’s original

homesteads -- in fact, Winslow had not yet formally existed when the Warners had taken possession

of the parcel. John’s father had died before John had turned

eleven. He had for several years thereafter served as the head of the household, responsible for the

support of his older sister and three younger brothers, until his mother had remarried in 1862. Cast

into the workforce early, John had acquired a variety of skills. Among them was an understanding of

machinery and of mill equipment. (His father had been a sawmiller, and briefly a partner of John

Bradford.) His introduction to Nellie may well

have resulted from his job helping to maintain gristmill and sawmill equipment at the Martin mills.

Their relationship blossomed into a courtship and they were married 21 April 1869. As was often the

case of marriages between Martintown or Winslow residents, the couple ventured up to Monroe, the

seat of Green County, to take care of the bureaucratic aspects. The rites there were conducted by

Justice of the Peace S.W. Abbott and witnessed by a pair of Monroe residents, M.J. Gardner and Mary

Reynolds. Neither of those women appear to have been individuals who knew John and Nellie well, and

S.W. Abbott himself had no direct connection -- they were just the people available on the spur of

the moment. The “real” wedding was held in Martintown in front of the full gaggle of kinfolk and

friends.

As the eldest daughter of the wealthiest man in the

immediate vicinity, Nellie was quite a prize to be had as far as suitors were concerned. But Nellie

did not concern herself with her social position; she wanted a mate of good character over all else.

And so she accepted the attentions of John Warner of Winslow. John, born 24 February 1847, was the

son of John Warner and Marancy Alexander, both formerly of New York state, and among the region’s

pioneers. John Sr. and Marancy had wed in 1841 and established one of Winslow’s original

homesteads -- in fact, Winslow had not yet formally existed when the Warners had taken possession

of the parcel. John’s father had died before John had turned

eleven. He had for several years thereafter served as the head of the household, responsible for the

support of his older sister and three younger brothers, until his mother had remarried in 1862. Cast

into the workforce early, John had acquired a variety of skills. Among them was an understanding of

machinery and of mill equipment. (His father had been a sawmiller, and briefly a partner of John

Bradford.) His introduction to Nellie may well

have resulted from his job helping to maintain gristmill and sawmill equipment at the Martin mills.

Their relationship blossomed into a courtship and they were married 21 April 1869. As was often the

case of marriages between Martintown or Winslow residents, the couple ventured up to Monroe, the

seat of Green County, to take care of the bureaucratic aspects. The rites there were conducted by

Justice of the Peace S.W. Abbott and witnessed by a pair of Monroe residents, M.J. Gardner and Mary

Reynolds. Neither of those women appear to have been individuals who knew John and Nellie well, and

S.W. Abbott himself had no direct connection -- they were just the people available on the spur of

the moment. The “real” wedding was held in Martintown in front of the full gaggle of kinfolk and

friends.

Minnie rapidly worsened. She died at the beginning of 1906. At

that point, Cullen’s doctor recommended he

be taken to a region with an arid climate to slow down the course of his own infection. The physician may

also have made it clear that the measure would help prevent other family members from contracting the

disease. Nellie and John’s response was profound. Despite the deep roots in southern Wisconsin and northern

Illinois, they accepted that the humidity and the cold winters were not what Cullen should be asked to put

up with any longer. Several of Nellie’s first cousins had settled in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

These cousins included her aunt Elizabeth Strader’s sons Elias Frame, William Patterson Frame, and Jacob

Silas Frame. The dry heat sounded like it was “just what the doctor ordered” and the Frames

recommended the area for other reasons. So Nellie and John headed off to Fresno County in December, 1906.

Minnie rapidly worsened. She died at the beginning of 1906. At

that point, Cullen’s doctor recommended he

be taken to a region with an arid climate to slow down the course of his own infection. The physician may

also have made it clear that the measure would help prevent other family members from contracting the

disease. Nellie and John’s response was profound. Despite the deep roots in southern Wisconsin and northern

Illinois, they accepted that the humidity and the cold winters were not what Cullen should be asked to put

up with any longer. Several of Nellie’s first cousins had settled in the San Joaquin Valley of California.

These cousins included her aunt Elizabeth Strader’s sons Elias Frame, William Patterson Frame, and Jacob

Silas Frame. The dry heat sounded like it was “just what the doctor ordered” and the Frames

recommended the area for other reasons. So Nellie and John headed off to Fresno County in December, 1906. The nearest post office was at the tiny trading post of

Academy, so inevitably when the family wrote home,

or were being written to, the address was simply “Academy.” Their name for their property was Spring Brook

Ranch, but this did not stick. When spoken of in later years, it was nearly always called “the Fancher

Creek place,” the name taken from the seasonal stream that ran through the parcel. A house was quickly built

to match the scale of the ample residence the family had enjoyed in Scioto Mills. (Shown left, the Fancher

Creek place and its main house.)

The nearest post office was at the tiny trading post of

Academy, so inevitably when the family wrote home,

or were being written to, the address was simply “Academy.” Their name for their property was Spring Brook

Ranch, but this did not stick. When spoken of in later years, it was nearly always called “the Fancher

Creek place,” the name taken from the seasonal stream that ran through the parcel. A house was quickly built

to match the scale of the ample residence the family had enjoyed in Scioto Mills. (Shown left, the Fancher

Creek place and its main house.) Nellie’s focus was largely upon Selma. She had been the mother

of eight, and now she was a mother one last time. As a man of his era, Cullen would not have been involved in

a lot of direct childcare even if he had been healthy, but that was even more the case given his potential

contagiousness. (At right, Nellie with Selma in about 1910.) It meant a great deal to Cullen to have his

daughter around, though, and Nellie was consoled that at least she could do that much for her ailing boy.

Nellie’s focus was largely upon Selma. She had been the mother

of eight, and now she was a mother one last time. As a man of his era, Cullen would not have been involved in

a lot of direct childcare even if he had been healthy, but that was even more the case given his potential

contagiousness. (At right, Nellie with Selma in about 1910.) It meant a great deal to Cullen to have his

daughter around, though, and Nellie was consoled that at least she could do that much for her ailing boy. The elder John, though excited by the enterprise and

certainly a big part of the planning and organization, was growing rickety enough that he was content to

supervise rather than commit to on-the-clock shifts as a warehouseman, nor was he even on-site every day.

That meant that right away, an additional

manager was needed to help John Martin Warner on the floor. Bert was hired to do that. His salary was sixty

dollars per month. This was generous enough that he knew he could support a wife, and soon have enough to buy

himself and that wife a house, so he and his sweetheart Grace Branson, a teacher at Round Mountain School in

the hills east of Spring Brook Ranch, set in motion their wedding plans. Meanwhile Alie Spece got in on the

income-earning potential by opening up a feed lot right next to the warehouse. Cattlemen of the hills were

in the habit of bringing stock down to Sanger to load them onto trains to go to market. The combination of

grain warehouse and feed lot right by the railroad tracks ensured Alie would have customers.

The elder John, though excited by the enterprise and

certainly a big part of the planning and organization, was growing rickety enough that he was content to

supervise rather than commit to on-the-clock shifts as a warehouseman, nor was he even on-site every day.

That meant that right away, an additional

manager was needed to help John Martin Warner on the floor. Bert was hired to do that. His salary was sixty

dollars per month. This was generous enough that he knew he could support a wife, and soon have enough to buy

himself and that wife a house, so he and his sweetheart Grace Branson, a teacher at Round Mountain School in

the hills east of Spring Brook Ranch, set in motion their wedding plans. Meanwhile Alie Spece got in on the

income-earning potential by opening up a feed lot right next to the warehouse. Cattlemen of the hills were

in the habit of bringing stock down to Sanger to load them onto trains to go to market. The combination of

grain warehouse and feed lot right by the railroad tracks ensured Alie would have customers. (Shown at right is

Nellie in the late summer of 1918 in an image from Emma’s collection, preserved by Emma’s heirs. This photo

was undoubtedly taken to commemorate Emma’s arrival; the occasion must have been the first time in

a dozen years that Emma had been able to pose for a group shot with so many of her siblings. The teenage

girl on the far left may be Selma but is more likely to be Erma Alice Spece. On the far right, the young

woman is Gladys Beryl Spece. The middle-aged individuals in this image are Nellie’s four eldest children.

In the back is Charles Elias Warner. From left to right in front are Mary Emma Warner Hastings, John Martin

Warner, and Cora Belle Warner Spece.)

(Shown at right is

Nellie in the late summer of 1918 in an image from Emma’s collection, preserved by Emma’s heirs. This photo

was undoubtedly taken to commemorate Emma’s arrival; the occasion must have been the first time in

a dozen years that Emma had been able to pose for a group shot with so many of her siblings. The teenage

girl on the far left may be Selma but is more likely to be Erma Alice Spece. On the far right, the young

woman is Gladys Beryl Spece. The middle-aged individuals in this image are Nellie’s four eldest children.

In the back is Charles Elias Warner. From left to right in front are Mary Emma Warner Hastings, John Martin

Warner, and Cora Belle Warner Spece.) (At left, Nellie poses with her first cousin Jake Frame.

The setting is probably the farm of Jake’s son William Washington Frame near Conejo in southern Fresno

County. The apparent ages of the pair make it clear the photo was taken in the 1920s.)

(At left, Nellie poses with her first cousin Jake Frame.

The setting is probably the farm of Jake’s son William Washington Frame near Conejo in southern Fresno

County. The apparent ages of the pair make it clear the photo was taken in the 1920s.)