John

Warner

John Warner, second child and eldest son of John Warner and Marancy

Alexander, was born 24 February 1847 in Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. He was his father’s namesake, but

does not seem to have been a “Junior” and will not be referred to as such in this biography, although

sometimes on the other pages of this website he is called that in order to make clear which John Warner is

being discussed. It could be that the two Johns had different middle names.

John Warner, second child and eldest son of John Warner and Marancy

Alexander, was born 24 February 1847 in Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. He was his father’s namesake, but

does not seem to have been a “Junior” and will not be referred to as such in this biography, although

sometimes on the other pages of this website he is called that in order to make clear which John Warner is

being discussed. It could be that the two Johns had different middle names.

John’s childhood was radically shaped by the death of his father 5 January, 1858. Given that the

late 1850s were not a time when widows were offered good-paying jobs, and given that Marancy still had

fairly small children to care for, it was up to John as the eldest surviving male of the household to support

the family, even though he had not quite turned eleven at the time of the tragedy. He waited just long enough

to graduate from the sixth grade, then at age twelve assumed the responsibility. (Despite having a limited

education, his clerical skills did not suffer and in middle age he would slip into professions which required

skills in reading, writing, and record-keeping.) Precisely what type of work he found at age twelve is not

recorded. It was probably a variety of odd jobs at first. However, it is worth noting that his father was a

miller. Young John may have had some opportunity to follow in those footsteps. If so, this would surely have

brought him to the huge mills of Nathaniel Martin, a mile north of Winslow in the village then known as

Martin, that would later be relabelled Martintown. This location was just barely over the state line in Green

County, WI. This employment scenario, while undocumented, would help explain how he came to know his future

wife Eleanor Amelia Martin, daughter of Nathaniel. Another link is that John’s first cousin Robert

Emmett Mack temporarily lived two or three houses away from Nathaniel and Hannah in the late 1860s, while

working as a Martintown blacksmith.

In the summer of 1862 Marancy Alexander married a neighbor, Nicholas Balliet, who had recently become a

widower. John no longer had to be the man of the household. Nor was he even the eldest male child. He had

at least two Balliet step-brothers who were senior to him, though one of those was so much older he had

already made his own way in the world. The other, David M. Balliet, was one year older.

The extended period without a father must have left John with a degree of pride and independence that

could not be suppressed. John was part of a generation whose young males were measured by their willingness

to show their courage and determination, so he chafed to join the Union Army and fight in the Civil War. He

attempted to do so as early as sixteen, but was rebuffed by the local recruiting officer, who knew him and

was aware John was too young. At seventeen, by taking advantage of a recruiter several miles away in the

village of Lena, John succeeded in his ambition. He enlisted 28 May 1864 and on the eighteenth of June was

inducted into Company F of the 142nd Infantry Regiment, Illinois at Camp Butler near Springfield. He must

have indulged his mother to a degree by signing up only for a 100-day term. (The 100 days apparently did

not count the adminstrative periods and boot camp. His tenure as a soldier was actually just short of five

months, or 150 days.) He was accompanied on his adventure by Aquilla Ballenger, who was even younger -- not

turning seventeen until the middle of their hitch. Aquilla was the stepson of John’s uncle Seba White.

John did not see combat. When Company F got to White’s Station, TN, he came down with malaria. This

naturally left him subject to recurring bouts of fever and weakness, complicated by a severe case of

diarrhea. When Company F went on to the battlefront, he was declared too sick to go. After he was back

on his feet, he was instead assigned to guard duty in St. Louis, MO, where the army was endeavoring to

protect critical railroad lines from saboteurs. This apparently represents the only active role John

played in the war. He was mustered out 26 October 1864 at Chicago, IL.

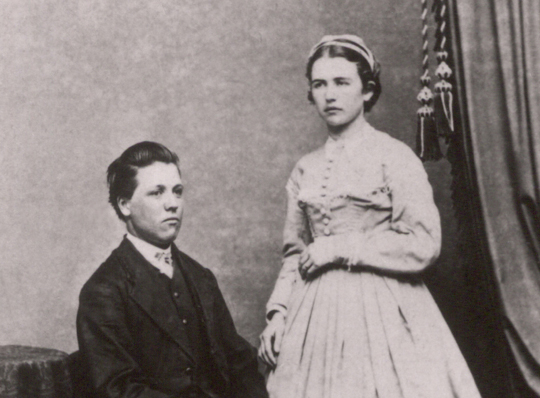

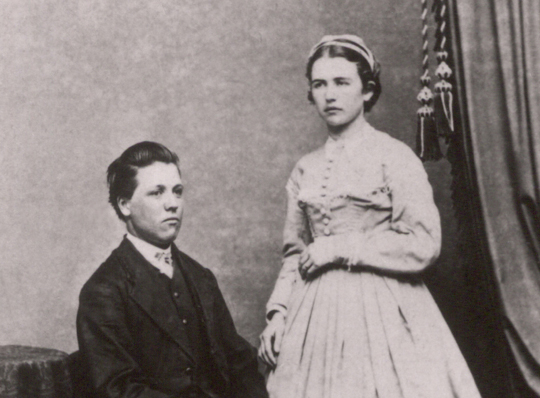

(The photograph at the upper left was scanned from a tintype preserved by John’s son Albert Frederick

Warner. The image dates from the Civil War period and probably shows John at about age fifteen or sixteen.

Though this is a low-resolution version, perhaps you can see the wispy traces of a beard along his jawline.

Had he died in the war like so many other young American men of his generation, this might have been the only photograph of John ever to exist. John’s military file describes him as 5’5” tall, with hazel eyes, a

dark complexion, and dark hair. A physical exam conducted in 1906 would put his height at 5’9”. It must be

that at age seventeen he had not reached his full adult height.

Like John, Aquilla Ballenger returned safely, going on to spend over sixty years residing in Schuyler

County, MO, where he did not pass away until he was nearly eighty-three years old. Another comrade from

Company F was Lorenzo Fuller. He was among the men who did get to go on to the front. He, too, came

back safely and was a friend of John’s until John’s dying day. Also surviving was David Balliet, who joined

up a couple of weeks before John was mustered out, as if to take his step-brother’s place. He came back

able to boast of having been issued a cartridge rifle, an advance in weaponry John had narrowly missed out

on. Yet another who returned was John’s first cousin Harvey Mack. His survival was the most remarkable of

the group, because he served for years and was part of such famous campaigns as Sherman’s March to the Sea.

Unfortunately not all Winslow-area men were so fortunate. The casualties included John’s other cousins George

C. and Harry A. Mack.

Though the war went on past John’s eighteenth birthday, he did not reenlist. It may be that Nicholas

Balliet had entered the period of ill health that would claim his life, though he remained alive long enough

to be noted in the 1865 state census. If so, John would have been needed once again as a breadwinner.

John may have worked at the sawmill of Nathaniel Martin before his military hitch, possibly coming

on board as a temporary replacement for grown men who were off at war. He unquestionably was employed

there during the post-war period, and as mentioned above, this brought him within the sphere of the

Martin family, leading to a romance between John and Nellie Martin. It is safe to say she was quite a

catch. She was almost out of his league. She was the eldest daughter of a village founder and reigning

patriarch, the biggest landowner within miles. Nellie could have had her pick of any number of suitors,

but she chose John. There is a hint in surviving documentation that the couple may have eloped. The

bureaucratic aspects of the union were dealt with ten miles northeast of Martintown and Winslow in Monroe,

the county seat of Green County. The rites were conducted by Justice of the Peace S.W. Abbott and witnessed

by a pair of Monroe residents, M.J. Gardner and Mary Reynolds, neither of whom seem to be individuals who

knew John and Nellie well, but were simply near at hand when the vows were said and the paperwork

processed. By the time the big wedding was held in Martintown in front of a host of family and

friends, no one was in a position to thwart their becoming man and wife. The wedding date was 21 April

1869.

Nellie, as a member of the clan of Nathaniel Martin and his wife Hannah Strader, is the subject of

a full biography on another section of this website. For more about her and her background, click

here.

John Warner and Eleanor Amelia Martin on their wedding day, 1869.

The marriage placed John in distinctly different economic circumstances than his mother and siblings. As

a dowry gift, Nathaniel gave the young couple eighty acres of farmland at the edge of Martintown, along the

Pecatonica River in Green County. In the coming decades there may have been occasional seasons when money

was less plentiful than at other times, but he could never again be said to be poor. Not surprisingly, this

level of security resulted in John putting down roots with Nellie in Martintown for decades. This stands in

contrast to the rest of the Warner family. Over the course of the 1870s all of his full siblings -- his older

sister was Araminta, his younger brothers were Fred, Clifford, and Charles -- left for Nebraska, where

homesteading opportunities allowed them and their young families to have a chance to prosper. It is thought

that his Balliet step-siblings all left as well, with the possible exception of Susan Balliet. (Her married

name is unknown, and so she has not been tracked past the 1870 census, when she was nineteen and getting by

as a domestic servant in Winslow.) John would seldom see his birth family members in the flesh from that point

on.

For the first year or so of the marriage, John and Nellie lived in Winslow, then inhabited their land at

Martintown. His main occupation over the next two decades was farmer, but he did not

limit himself to only that. He is thought to have stayed involved with the community in other ways, and

probably helped from time to time with the Martintown sawmill. The children began arriving in 1870 and

continued to be born every even-numbered year through 1886, skipping 1880 (when Nellie endured a miscarriage).

In an age when children were often lost young -- Nathaniel and Hannah Martin lost half their fourteen children

during their childhoods -- John and Nellie lost only one. Their fifth child, Ida Ellen Warner, survived only

seventeen months from the late summer of 1878 to the early part of 1880. She fell victim to the same epidemic

of diphtheria that claimed the life of John’s little nephew Olan Carson Warner in Nebraska, as well Nellie’s

equally young niece Edna Brown right in Martintown. (The remains of both Ida and Edna were buried

in the Martin cemetery.)

Living under the shadow of such a prominent father-in-law does

not seem to have been a strain for John. In any case, he managed to do so for a good thirty years. There

was only one interruption in those circumstances, that being an interval spent in Howell County, MO. In

about 1883, Nellie’s sister Emma’s husband Cullen Penny Brown was hired to help establish a sawmill near

Willow Springs. Cullen must have enticed John with an employment opportunity, and so John and Nellie

and the kids relocated. They remained at least a year and possibly two. Seventh child Albert Frederick Warner

was born during the midst of this sojourn. In 1885 or so the family returned to Martintown. They were

certainly back by 1886, when eighth and final

child Walter Clare Warner was born. (The Browns did not linger in Howell County, either.)

Living under the shadow of such a prominent father-in-law does

not seem to have been a strain for John. In any case, he managed to do so for a good thirty years. There

was only one interruption in those circumstances, that being an interval spent in Howell County, MO. In

about 1883, Nellie’s sister Emma’s husband Cullen Penny Brown was hired to help establish a sawmill near

Willow Springs. Cullen must have enticed John with an employment opportunity, and so John and Nellie

and the kids relocated. They remained at least a year and possibly two. Seventh child Albert Frederick Warner

was born during the midst of this sojourn. In 1885 or so the family returned to Martintown. They were

certainly back by 1886, when eighth and final

child Walter Clare Warner was born. (The Browns did not linger in Howell County, either.)

John doted upon his family and regarded fatherhood as one of the great blessings of his life. In addition to

the eight children, he and Nellie also served as foster parents for a period in the late 1870s and early

1880s of two of Nellie’s first cousins, Henry and Isaiah Martin, sons of her uncle Charles Martin, whose

marriage had fallen apart. And later, as will be discussed, the couple helped raise their orphanned

granddaughter Selma Warner.

Farming lost its allure for John, though he and Nellie continued to own their acreage. As his older two boys

came of age he let them handle more and more of the agricultural chores and spent the 1890s pursuing other

interests. One of the minor occupations was insurance agent. (The photograph at left shows him during that

phase of his life, wearing his business suit.) Another minor one was to serve as a justice of the

peace for Green County. When Nellie’s youngest sister Juliette married her husband Edwin Savage in the

mid-1890s, it was John who signed the marriage certificate. These sidelines did not keep him from his

main ambition, which could be described as being an entrepreneur and/or investor. John understood quite well

the principle

of letting his money make money. Most of these ventures were family-oriented, though. For instance,

he and Nellie were surely the source of capital behind the purchase in approximately 1892 of a steam

tractor and threshing rig that his older two sons, and later his younger son Cullen, would operate as

the so-called Warner Brothers. This rig and its operators were leased out at harvest time to farmers

across a broad swath of northern Stephenson County and southern Green County. Everyone in the area was

familiar with the brothers and their rig -- its double steam whistle could be heard from miles away. (To

see a photo of the rig in operation, click here and scroll down to the bottom

of the page.)

During the 1890s three of the four oldest children acquired spouses and founded families. The three

were John Martin Warner, who married Anna Lueck, Mary Emma Warner, who married Fred Philo Hastings, and

Cora Belle Warner, who married Alfonso James Spece. All three couples began farming in Green County. Son

Charley was the exception. Though Charley farmed in Green County (upon land deeded to him

by his Martin grandparents), he remained a bachelor, living off and on with John and Nellie.

Eventually John and Nellie began untying the cords that

had kept them so closely tied to the immediate vicinity of their births. John had long been acquainted with

the sales side of running a lumber mill and lumber business. In the 1890s he was partners with Dayton Tyler

in Tyler & Warner, a firm that produced custom lumber at Tyler’s mill on the former Saucerman property a

mile or so north of Martintown, next to Saucerman Cemetery, where Nellie’s maternal grandparents were buried.

John apparently also was involved with finding customers for the large lumber mill about ten miles southeast

of Martintown at Scioto Mills, Stephenson County, IL. The latter activity grew to be so integral to the

household finances that John convinced Nellie to move to Scioto Mills in the latter half of the year 1900.

Their bachelor sons, some of whom were still only in high school, were part of this move, with elder son

Charley becoming John’s partner in a new custom lumber firm, Warner & Son. After 1900, when newspapers

referred to John Warner of Martintown, they meant John Martin Warner, who was the proprietor of one of

the village’s general stores, unless the reporter specifically said, “John Warner Sr.” (Shown at right

is the family’s Scioto Mills residence.)

Eventually John and Nellie began untying the cords that

had kept them so closely tied to the immediate vicinity of their births. John had long been acquainted with

the sales side of running a lumber mill and lumber business. In the 1890s he was partners with Dayton Tyler

in Tyler & Warner, a firm that produced custom lumber at Tyler’s mill on the former Saucerman property a

mile or so north of Martintown, next to Saucerman Cemetery, where Nellie’s maternal grandparents were buried.

John apparently also was involved with finding customers for the large lumber mill about ten miles southeast

of Martintown at Scioto Mills, Stephenson County, IL. The latter activity grew to be so integral to the

household finances that John convinced Nellie to move to Scioto Mills in the latter half of the year 1900.

Their bachelor sons, some of whom were still only in high school, were part of this move, with elder son

Charley becoming John’s partner in a new custom lumber firm, Warner & Son. After 1900, when newspapers

referred to John Warner of Martintown, they meant John Martin Warner, who was the proprietor of one of

the village’s general stores, unless the reporter specifically said, “John Warner Sr.” (Shown at right

is the family’s Scioto Mills residence.)

In the latter part of 1903, another of John and Nellie’s children married -- though somewhat

precipitously. Cullen Clifford Warner’s girlfriend Minnie Brecklin had become pregnant, and so

a wedding was hastily arranged. Daughter Selma was born the following May. Almost at once fate began to

“dump on” the young couple. Minnie and Cullen developed tuberculosis, a scourge that was running

rampant in the area. John and Nellie rose to the occasion in a proactive way. They set up an

enclosed-porch “sanitarium” section at their Scioto Mills house to accommodate Cullen and Minnie and

isolate little Selma from them, and as a whole family did whatever they could to help. Despite their

best efforts, Minnie declined rapidly and passed away in early 1906. The family doctor

expressed the opinion that Cullen did not have much time left unless he was removed to a place with an

arid climate. The family again responded rapidly and profoundly. Some of Nellie’s cousins, the Frames,

had moved to the San Joaquin Valley of California in the 1890s, and had successfully established

themselves there. John and Nellie decided to follow suit. With the exception of Charley, the whole

Scioto Mills household went west. Bert was sent on ahead in early December with a whole rail car

stuffed with family possessions, including the buggy and team of horses, heading for

the depot at Fowler, Fresno County, CA, a few miles from the farm of Will Frame. Bert was accompanied

by his first cousin Fay Horatio Martin, who had lost his own father to TB in April of that year.

While Bert and Fay were making their slow freight-train journey across the continent, the remaining

family members prepared for their faster, passenger-train crossing. They lingered in Illinois long

enough to allow

Walter to marry his his sweetheart Margaret Jane Bell. The wedding took place 12 December 1906 in

Freeport. Three days later, John, Nellie, Cullen, Selma, Walter, and Margaret departed. All of them

would be Californians for the rest of their lives. The same was true of Bert, though it was not the

case with Fay Martin, who stayed Out West only a few weeks.

John and Nellie wished to have a home with the stature of their Martintown holdings, i.e. a substantial

piece of acreage that would serve as the family estate and pass down to later generations. They also

needed to put Cullen in a situation where he would expose as few people as

possible to tuberculosis. The solution was that early in 1907, John and Nellie bought a large piece of land

east of the towns of Fresno and Clovis at the edge of the foothills, near the small trading post of

Academy. It was near a seasonal stream called Fancher Creek, and in later years the property was referred

to in memory among the family variously as “the ranch at Academy” or “the Fancher Creek place.” However,

while it was a part of the family’s day-to-day existence it also bore the more affectionate name of

Spring Brook Ranch. A large house was built. However, it was only to be John and Nellie's home on a

part-time basis. For the most part, they stayed in a house in the town of Sanger, ten miles due south

of Academy out in the San Joaquin Valley proper. They kept Selma with them. Bert and Cullen were the

full-time occupants of the ranch house. Walter and Margaret’s home was also on Spring Brook Ranch, though

they stayed not in the main house but in a separate shack, where they could have some privacy. The pair

were often gone, working with their Frame cousins as migrant workers in orchards and fruit-packing sheds

up and down the valley, and then in early 1909, having become parents, they bought a twenty-acre farm of

their own in the Fowler area, near Will Frame’s place.

Spring Brook Ranch (shown at left, photo possibly taken

during the era the family lived there) never achieved the stature of family estate. John had thought

like an Illinois man

and assumed summer rains would allow agriculture. He didn’t realize how profoundly rain-free the San

Joaquin Valley and Sierra Nevada foothills are from May to October. When Cullen succumbed to

his illness at the beginning of May, 1909, the ranch lost its sanitarium purpose, and it began to seem

pointless to hang on to it. The acreage was useful as pasture land, but John had Nellie had meant for

it to be much more. They would go on to sell the property in 1911.

Spring Brook Ranch (shown at left, photo possibly taken

during the era the family lived there) never achieved the stature of family estate. John had thought

like an Illinois man

and assumed summer rains would allow agriculture. He didn’t realize how profoundly rain-free the San

Joaquin Valley and Sierra Nevada foothills are from May to October. When Cullen succumbed to

his illness at the beginning of May, 1909, the ranch lost its sanitarium purpose, and it began to seem

pointless to hang on to it. The acreage was useful as pasture land, but John had Nellie had meant for

it to be much more. They would go on to sell the property in 1911.

Meanwhile, other developments increased their bonds with Sanger. By the time of Cullen’s death, daughter

Belle and son-in-law Alie Spece and their girls arrived, Alie having given up on his cheese-factory

ambitions back in Green County, WI. Then in early 1910, John and Anna Lueck Warner arrived with their

two kids, Anna’s own case of TB having warranted a relocation to the aridity of California. John, Sr.

teamed up with his namesake son and founded a large feed grain warehouse and hardware store called

Warner & Warner. When completed, and for years afterward, it was the largest building in Sanger.

Local historians would eventually proclaim it to have been Sanger’s first truly urban building, marking

the transition from sawmill village/lumber-shipment outpost to actual town. Alie Spece, who with Belle

had made do with day jobs -- including fruit harvest work alongside the Frame relatives, as in the manner

of Walter and Margaret -- founded a feed lot beside the warehouse.

Things seemed well set for a long, happy, settled period among the clan as Sanger merchants, which

naturally suited John quite well. Son Charley even joined in, having belatedly given up his ties to

Scioto Mills and rejoined his kinfolk. But the next three years produced a great deal of grief to pile

on top of the recent

loss of Cullen. Anna Lueck Warner’s case of tuberculosis deepened. She passed away back in Wisconsin

in the spring of 1911. Walter and Margaret’s little son Clare was discovered to have TB as well, and

he would only last until 1913. Soon the business arrangement of Warner & Warner was forced to evolve.

Younger John decided to sell out in 1913, his domestic situation being too much in flux. Elder John

decided that, at age sixty-six, he should retire. With Charley having become a farmer on

his own, that left two men of the family as prospects to take over the warehouse -- Bert and Alie.

Alie had recently given up on the feed lot and was not enjoying his alternate occupation of peach

farmer. Bert had already been co-managing the warehouse for two years as an employee, having married

Grace Branson, a young woman who had been teaching school near Spring

Brook Ranch, and having settled in Sanger. So Bert and Alie became owners of Warner & Warner.

Although he had acknowledged having entered his

rocking-chair phase of life, John couldn’t resist being active. He probably felt he was privileged

just to be alive at such an age. His immediate clan had not shown much longevity. His youngest

brother Charles had died in his mid-forties, just as their father had. Fred had died at fifty and

Minta at sixty-five. Minta’s death certificate shows she died of a stroke. That was probably what

claimed all of the others, too. It would be John’s cause of death as well. But in the meantime, John

savored what time he had left. Happily, he was still thriving in 1915 when an old veteran happened

to stop by at Warner & Warner and asked the background of the owners, because he recalled serving with

a John Warner in the 142nd Illinois Regiment during the Civil War. Bert summoned his father. The

two old men had a grand time reminiscing.

Although he had acknowledged having entered his

rocking-chair phase of life, John couldn’t resist being active. He probably felt he was privileged

just to be alive at such an age. His immediate clan had not shown much longevity. His youngest

brother Charles had died in his mid-forties, just as their father had. Fred had died at fifty and

Minta at sixty-five. Minta’s death certificate shows she died of a stroke. That was probably what

claimed all of the others, too. It would be John’s cause of death as well. But in the meantime, John

savored what time he had left. Happily, he was still thriving in 1915 when an old veteran happened

to stop by at Warner & Warner and asked the background of the owners, because he recalled serving with

a John Warner in the 142nd Illinois Regiment during the Civil War. Bert summoned his father. The

two old men had a grand time reminiscing.

The timing of the encounter was fortuitous, because John had only a matter of months to live. The

aforementioned stroke took him suddenly 3 January 1916 while he was up in the Fresno County hills,

probably visiting his son Walter, who was working in the area at the time, or perhaps even personally

calling upon lumber producers as a sales broker, unable to resist dabbling in his old career. His body

was brought down the mountain to Tollhouse. That small community, which would in later years be the

main residence of his granddaughter Marian Warner Weldon, was where the death certificate was completed

and so Tollhouse was entered as his official place of death. He was buried 11 January 1916 at Mendocino

Avenue Cemetery on the outskirts of Parlier, Fresno County, CA, a few miles south of Sanger. The grave

was next to that of his little grandson, Elbert Clare Warner.

In her widowhood, at first with young Selma still under her care, Nellie depended on son Charles Elias

Warner to be the man of the house. For more about this final period of her life, refer to her

biography. Nellie passed away 21 February 1930 at the home of her daughter Belle and son-in-law Alie

Spece on their peach farm in southern Fresno County near the little town of Del Rey, in the vicinity

of the homes and farms of some of her Frame cousins. Her remains were placed with those of John at

Mendocino Avenue Cemetery. Many decades later the next grave over (on the side opposite little Clare

Warner’s plot) would be occupied by the remains of son Bert and his wife, Grace Mildred Branson

Warner.

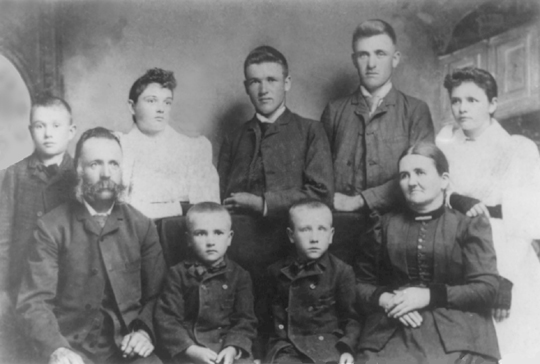

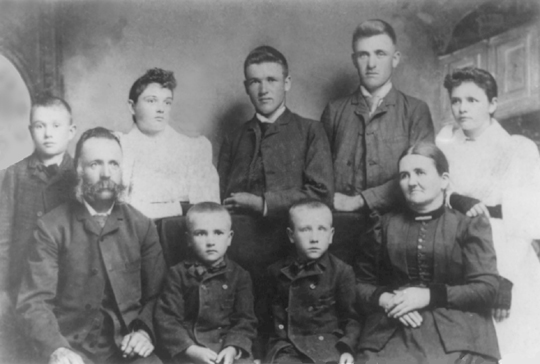

Taken in the early 1890s, this formal portrait shows the entire family of John Warner

and Nellie Martin, with the exception of their daughter Ida Ellen Warner, who had died as a toddler

in 1880. John is seated at left, Nellie on the right, with youngest sons Walter (l) and Bert (r)

seated between them. Standing in the back are, left to right, Cullen, Cora Belle, Charles, John,

and Emma.

Children of Eleanor Amelia “Nellie” Martin

with John Warner

John Martin

Warner

Charles Elias

Warner

Mary Emma

Warner

Cora Belle

Warner

Ida Ellen

Warner

Cullen Clifford

Warner

Albert Frederick

Warner

Walter Clare

Warner

For genealogical details, click on

each of the names.

To return to the Warner/Alexander Family main page, click here. To

return to Nellie Martin’s biography, click here.

John Warner, second child and eldest son of John Warner and Marancy

Alexander, was born 24 February 1847 in Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. He was his father’s namesake, but

does not seem to have been a “Junior” and will not be referred to as such in this biography, although

sometimes on the other pages of this website he is called that in order to make clear which John Warner is

being discussed. It could be that the two Johns had different middle names.

John Warner, second child and eldest son of John Warner and Marancy

Alexander, was born 24 February 1847 in Winslow, Stephenson County, IL. He was his father’s namesake, but

does not seem to have been a “Junior” and will not be referred to as such in this biography, although

sometimes on the other pages of this website he is called that in order to make clear which John Warner is

being discussed. It could be that the two Johns had different middle names.

Living under the shadow of such a prominent father-in-law does

not seem to have been a strain for John. In any case, he managed to do so for a good thirty years. There

was only one interruption in those circumstances, that being an interval spent in Howell County, MO. In

about 1883, Nellie’s sister Emma’s husband Cullen Penny Brown was hired to help establish a sawmill near

Willow Springs. Cullen must have enticed John with an employment opportunity, and so John and Nellie

and the kids relocated. They remained at least a year and possibly two. Seventh child Albert Frederick Warner

was born during the midst of this sojourn. In 1885 or so the family returned to Martintown. They were

certainly back by 1886, when eighth and final

child Walter Clare Warner was born. (The Browns did not linger in Howell County, either.)

Living under the shadow of such a prominent father-in-law does

not seem to have been a strain for John. In any case, he managed to do so for a good thirty years. There

was only one interruption in those circumstances, that being an interval spent in Howell County, MO. In

about 1883, Nellie’s sister Emma’s husband Cullen Penny Brown was hired to help establish a sawmill near

Willow Springs. Cullen must have enticed John with an employment opportunity, and so John and Nellie

and the kids relocated. They remained at least a year and possibly two. Seventh child Albert Frederick Warner

was born during the midst of this sojourn. In 1885 or so the family returned to Martintown. They were

certainly back by 1886, when eighth and final

child Walter Clare Warner was born. (The Browns did not linger in Howell County, either.) Eventually John and Nellie began untying the cords that

had kept them so closely tied to the immediate vicinity of their births. John had long been acquainted with

the sales side of running a lumber mill and lumber business. In the 1890s he was partners with Dayton Tyler

in Tyler & Warner, a firm that produced custom lumber at Tyler’s mill on the former Saucerman property a

mile or so north of Martintown, next to Saucerman Cemetery, where Nellie’s maternal grandparents were buried.

John apparently also was involved with finding customers for the large lumber mill about ten miles southeast

of Martintown at Scioto Mills, Stephenson County, IL. The latter activity grew to be so integral to the

household finances that John convinced Nellie to move to Scioto Mills in the latter half of the year 1900.

Their bachelor sons, some of whom were still only in high school, were part of this move, with elder son

Charley becoming John’s partner in a new custom lumber firm, Warner & Son. After 1900, when newspapers

referred to John Warner of Martintown, they meant John Martin Warner, who was the proprietor of one of

the village’s general stores, unless the reporter specifically said, “John Warner Sr.” (Shown at right

is the family’s Scioto Mills residence.)

Eventually John and Nellie began untying the cords that

had kept them so closely tied to the immediate vicinity of their births. John had long been acquainted with

the sales side of running a lumber mill and lumber business. In the 1890s he was partners with Dayton Tyler

in Tyler & Warner, a firm that produced custom lumber at Tyler’s mill on the former Saucerman property a

mile or so north of Martintown, next to Saucerman Cemetery, where Nellie’s maternal grandparents were buried.

John apparently also was involved with finding customers for the large lumber mill about ten miles southeast

of Martintown at Scioto Mills, Stephenson County, IL. The latter activity grew to be so integral to the

household finances that John convinced Nellie to move to Scioto Mills in the latter half of the year 1900.

Their bachelor sons, some of whom were still only in high school, were part of this move, with elder son

Charley becoming John’s partner in a new custom lumber firm, Warner & Son. After 1900, when newspapers

referred to John Warner of Martintown, they meant John Martin Warner, who was the proprietor of one of

the village’s general stores, unless the reporter specifically said, “John Warner Sr.” (Shown at right

is the family’s Scioto Mills residence.) Spring Brook Ranch (shown at left, photo possibly taken

during the era the family lived there) never achieved the stature of family estate. John had thought

like an Illinois man

and assumed summer rains would allow agriculture. He didn’t realize how profoundly rain-free the San

Joaquin Valley and Sierra Nevada foothills are from May to October. When Cullen succumbed to

his illness at the beginning of May, 1909, the ranch lost its sanitarium purpose, and it began to seem

pointless to hang on to it. The acreage was useful as pasture land, but John had Nellie had meant for

it to be much more. They would go on to sell the property in 1911.

Spring Brook Ranch (shown at left, photo possibly taken

during the era the family lived there) never achieved the stature of family estate. John had thought

like an Illinois man

and assumed summer rains would allow agriculture. He didn’t realize how profoundly rain-free the San

Joaquin Valley and Sierra Nevada foothills are from May to October. When Cullen succumbed to

his illness at the beginning of May, 1909, the ranch lost its sanitarium purpose, and it began to seem

pointless to hang on to it. The acreage was useful as pasture land, but John had Nellie had meant for

it to be much more. They would go on to sell the property in 1911. Although he had acknowledged having entered his

rocking-chair phase of life, John couldn’t resist being active. He probably felt he was privileged

just to be alive at such an age. His immediate clan had not shown much longevity. His youngest

brother Charles had died in his mid-forties, just as their father had. Fred had died at fifty and

Minta at sixty-five. Minta’s death certificate shows she died of a stroke. That was probably what

claimed all of the others, too. It would be John’s cause of death as well. But in the meantime, John

savored what time he had left. Happily, he was still thriving in 1915 when an old veteran happened

to stop by at Warner & Warner and asked the background of the owners, because he recalled serving with

a John Warner in the 142nd Illinois Regiment during the Civil War. Bert summoned his father. The

two old men had a grand time reminiscing.

Although he had acknowledged having entered his

rocking-chair phase of life, John couldn’t resist being active. He probably felt he was privileged

just to be alive at such an age. His immediate clan had not shown much longevity. His youngest

brother Charles had died in his mid-forties, just as their father had. Fred had died at fifty and

Minta at sixty-five. Minta’s death certificate shows she died of a stroke. That was probably what

claimed all of the others, too. It would be John’s cause of death as well. But in the meantime, John

savored what time he had left. Happily, he was still thriving in 1915 when an old veteran happened

to stop by at Warner & Warner and asked the background of the owners, because he recalled serving with

a John Warner in the 142nd Illinois Regiment during the Civil War. Bert summoned his father. The

two old men had a grand time reminiscing.