Nathaniel Martin

Nathaniel Martin is the patriarch of the clan this

website is devoted to. Accordingly, he gets special attention here. He is also a figure of special

interest as part of the history of Green County, WI. In 1901, when Nathaniel was an old man, the

following tribute to him was published in the Commemorative Biographical Record of the Counties

of Rock, Green, Grant, Iowa, and Lafayette, Wisconsin on pages 755-756. (The capitalization and

abbreviation style has been altered to conform to modern common usage. The parentheses you see were

part of the original text.)

Nathaniel Martin is the patriarch of the clan this

website is devoted to. Accordingly, he gets special attention here. He is also a figure of special

interest as part of the history of Green County, WI. In 1901, when Nathaniel was an old man, the

following tribute to him was published in the Commemorative Biographical Record of the Counties

of Rock, Green, Grant, Iowa, and Lafayette, Wisconsin on pages 755-756. (The capitalization and

abbreviation style has been altered to conform to modern common usage. The parentheses you see were

part of the original text.)

NATHANIEL MARTIN, whose name in Cadiz Township, Green County, is “familiar as household words,”

is a native of Virginia, born December 14, 1816.

James and Rebecca (Pearcy) Martin, his parents, were also Virginians, and came of Irish and

English ancestry, respectively, Grandfather Martin having been born in Ireland, and

Grandfather Pearcy in England. James and Rebecca Martin had ten children: Sidney,

Redmond, Isaiah, Elias, Nathaniel, Rebecca, Nancy, Charles, Polly (who died in childhood),

and one whose name is not given, all now deceased except Nathaniel and Rebecca (Mrs. Burrell),

the latter of whom is residing in Nora, Illinois.

Nathaniel Martin was reared and educated in Virginia, whence, at the age of twenty, he went

to St. Louis, MO, and chopped wood for one winter. In the spring of 1837 he removed to

Stephenson County, IL, where for several years he worked at day wages. In 1848 he came

to Green County, WI, and built a dam on the Pecatonica River, at a point where the present

village of Martintown now stands, and the same year he erected a sawmill and later a

gristmill. Here for over fifty-two years he has conducted a general milling business with

remarkable success. Mr. Martin commenced life a poor boy, but by hard work, persistent and

judicious economy he has become one of the wealthiest men of Green County, at one time owning

1200 acres of fine land, over 200 of which were under cultivation. However, he has given

away most of his land, and is now devoting his time exclusively to operating the mills. For

more than half a century he has been one of the leading business men of Cadiz Township, and

the village of Martintown (known as “Martin” before the railroad was built to that point), where

he has his home, was platted by and named for him.

On February 25, 1847, Nathaniel Martin married Miss Hannah Strader, daughter of Jacob and Rachel

(Starr) Strader, who were among the early settlers of Green County, and fourteen children were

born of this union, viz.: Elias, who lives at Cripple Creek, CO, married Lavina, daughter

of Thomas Watson; Alice is deceased; her twin sister, Eleanor A., married John Warner, of

Winslow, IL; Jennie Edith, now deceased, was the wife of Jacob Hodge, late of Minnesota;

Horatio makes his home in Martintown, WI, being in partnership with his father in the

milling business (he married Laura Hart, and has four children); William and Charles are

both deceased; Emma is the wife of Cullen P. Brown, of Saint Marys, MO; Christa B. and

Abraham L. are deceased; Mary L. is the wife of Elwood Bucher, of Illinois; James F. is

deceased; Juliet B. is the wife of Edwin E. Savage, a machinist of Seattle, WA; and

Hannah is deceased. There are twenty-eight grandchildren and six great-grandchildren.

In politics Mr. Martin leans toward Prohibition, but was originally a Whig, later a

Republican, and during his long career in Green County has always declined to fill any

offices of honor and trust. In religious faith he accepts the strict interpretation of

the Scriptures, and is opposed to all dogmas and creed doctrines. He and his estimable

wife, who has been his faithful helpmeet for fifty-four years of joys and sorrows, live

in the enjoyment of the respect and esteem of a wide circle of friends and acquaintances.

This and other tributes portray Nathaniel as a noble and generous pioneer, not

merely a pillar of his community but the bedrock upon which it was laid. This portrait is

consistent with the description offered by descendants who knew him, such as his grandson Albert

Frederick “Bert” Warner, who spent most of his childhood in Martintown and knew Nathaniel

well -- Nathaniel did not die until Bert was twenty. Bert characterized his grandfather in

glowing terms, calling him “quite a fellow” and leading any listener to believe that Nathaniel

was the sort of person depended upon by the people around him. Modern-day investigation has shown

Nathaniel was very much that man, deserving of his accolades. However, he was a complex person,

and his full story has some wrinkles. What follows is as much of that full story as can be

assembled at this time:

Nathaniel was, as mentioned above, a son of James Martin and Rebecca Pearcy. James’s origin, other

than that he was a Virginian of Irish stock, is unknown. Rebecca Pearcy, daughter of James Pearcy

and Elizabeth “Betsy” Smelser, was born and raised in Bedford County, VA. About 1809, when Rebecca

was nineteen, the Pearcy family moved to Franklin County. Their new home was as little as a few miles,

and at most a few dozen miles, from their previous one; however, it was enough of a change of venue

to put them among new neighbors. This may

have been how Rebecca met James Martin, whom she married in Franklin County in the autumn of 1811.

(For more about James and Rebecca, and about Rebecca’s ancestry, see the page on this website

devoted to that subject. Click here to go straight to

that page.) James Pearcy and Betsy Smelser and a number of their children and grandchildren

relocated in the spring of 1817 to Wayne County, KY. James Martin and Rebecca Pearcy were not part

of this move. They appear to have ventured off as soon as they were married to establish their own

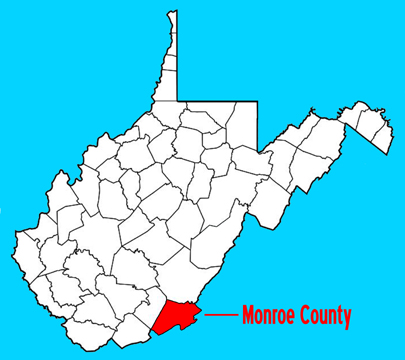

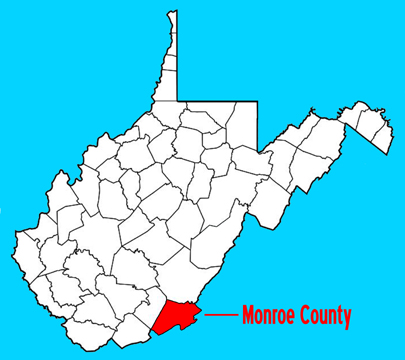

home in Monroe County in what is now West Virginia. Unfortunately, their paper trail vanishes after

the 1811 Franklin County marriage record and does not reappear until the 1838 Monroe County record of

the marriage of their daughter Sydney Martin to Jacob King. This quarter-century-plus span of

invisibility is a genealogical frustration, leaving open the possibility they were somewhere other than

Monroe County, but they do not appear in records elsewhere and there is one document that points to them

being in Monroe County right from the time they were newlyweds. That document is the county death register

entry for their daughter Sydney, who died of measles in 1853. Her birthplace is cited as being Monroe

County. The informant was her husband Jacob King. Although Jacob might have had an imperfect understanding

of his wife’s birthplace, he had every reason to know the correct stat and there is no evidence found so

far that would prove him wrong. We are left with speculation as to why the Martin family does not appear

in the expected spot in the 1820 and 1830 censuses. Perhaps they resided on property that was isolated

and was not reached by the censustakers. Perhaps they were part of a larger household and were enumerated

under the name of someone other than James. But taking Jacob King at his word, then it would seem that all

of James and Rebecca’s children were born in Monroe County. It can also be said that they were all raised

to adulthood there with the possible exception of the youngest member of the brood, Charles Alexander

Martin, who was probably still in his teens when James and Rebecca moved on to Raleigh County, VA.

Nathaniel’s boyhood home was a good one by the standards of

the day. Monroe County is only some sixty miles northwest of Franklin and Bedford Counties, so James and

Rebecca would not have found their new environment much different from what they were accustomed to. True,

it was closer to the frontier, but by the time they got there in late 1811 or early 1812, pioneers had been

improving the region for a couple of decades. At the same time, the population was still sparse enough

that prime alluvial-soil farmland was available along Second Creek. The stream itself ran fast, which had

led to, and would continue to lead to, the building of successful sawmills and grist mills. The creek, a

tributary of the Greenbrier River, also provided excellent fishing. These attributes help explain why

Nathaniel would end up making his career as a miller and would be remembered as a fisherman. The nature

of the place unquestionably had a formative influence upon him. It is remarkable that he left it behind

so completely when he reached manhood. Presumably he made visits back, but if not, then his departure for

St. Louis meant he never again saw his siblings Sydney and Redmond, who spent the rest of their lives in

West Virginia, and did not see his parents again for about fifteen years. To head off on such an adventure

with such boldness and commitment seems to have been characteristic of Nathaniel. Fortunately he was able

to preserve an on-going connection to his past. He was not alone during his wanderings. His slightly older

brother Isaiah came along. (Given that Isaiah was senior in age, it might be more appropriate to say

Nathaniel was the one who “came along.”) Nathaniel and Isaiah would be each other’s regular companions and

business partners through the late 1850s, a span covering a full twenty years.

Nathaniel’s boyhood home was a good one by the standards of

the day. Monroe County is only some sixty miles northwest of Franklin and Bedford Counties, so James and

Rebecca would not have found their new environment much different from what they were accustomed to. True,

it was closer to the frontier, but by the time they got there in late 1811 or early 1812, pioneers had been

improving the region for a couple of decades. At the same time, the population was still sparse enough

that prime alluvial-soil farmland was available along Second Creek. The stream itself ran fast, which had

led to, and would continue to lead to, the building of successful sawmills and grist mills. The creek, a

tributary of the Greenbrier River, also provided excellent fishing. These attributes help explain why

Nathaniel would end up making his career as a miller and would be remembered as a fisherman. The nature

of the place unquestionably had a formative influence upon him. It is remarkable that he left it behind

so completely when he reached manhood. Presumably he made visits back, but if not, then his departure for

St. Louis meant he never again saw his siblings Sydney and Redmond, who spent the rest of their lives in

West Virginia, and did not see his parents again for about fifteen years. To head off on such an adventure

with such boldness and commitment seems to have been characteristic of Nathaniel. Fortunately he was able

to preserve an on-going connection to his past. He was not alone during his wanderings. His slightly older

brother Isaiah came along. (Given that Isaiah was senior in age, it might be more appropriate to say

Nathaniel was the one who “came along.”) Nathaniel and Isaiah would be each other’s regular companions and

business partners through the late 1850s, a span covering a full twenty years.

Despite Monroe County’s relative isolation and its backwoods culture, Nathaniel somehow received a good

education. This is remarkable. A measure of how remarkable is displayed by his brother Redmond’s

circumstances. The 1880 Kanawha County, WV census shows that even at that late point in the century,

Redmond was the only member of the household who could read and write. Illiteracy was the rule there, and

had surely been even more the rule in 1820s and 1830s Monroe County. Who taught the Martin/Pearcy kids is

unknown, but the job was properly done. Perhaps Rebecca Pearcy Martin personally handled the task. If not,

it is safe to say she was an advocate of the idea that her children be schooled. A number of her

uncles and male first cousins are known to have been academically accomplished. Chances are good

that education was emphasized among the whole Pearcy clan. Nathaniel was well-read and could express himself

in writing in an erudite way. He had no problem doing the mathematical calculations a merchant needs to do.

Music was not neglected. He and all of his brothers played violin (fiddle). Nathaniel was reputed to be

able to do buck and wing dances equal to a stage artist.

The timing and route of Nathaniel and Isaiah’s journey from St. Louis to Stephenson County mirrors

that of land speculator William S. Russell. This is unlikely to be coincidence. Russell probably brought

the Martin boys with him, having already hired them for one or more jobs in St. Louis and been favorably

impressed with the results -- or he may have sent for them not long after his arrival in northern Illinois.

He would have been able to guarantee them work. Russell was the western agent

and largest single shareholder of the Boston & Western Land Company, a consortium of forty-three Eastern

investors, most of them based in Boston, MA. These speculators had combined forces in 1835 to enter

claims for soon-to-be-auctioned government lands in the West -- in their terms, the West consisting of

the portions of the upper central Mississippi River Valley that had come to be viewed as safe from attack

by native tribes in the wake of the white victories in the Black Hawk Wars of the early 1830s. B&WL sought

properties they imagined setters and/or other speculators would so eagerly want to acquire that the

partners would be able to sell out within just a few years and make enormous profits, as other men had

been able to do earlier in the 1830s. In 1837, William S. Russell set his sights upon a locale in

the northern portion of Stephenson County, IL where he felt sure a major town would grow. Per his

recommendation, the Boston & Western Land Company invested there heavily. The spot was at a bend in the

Pecatonica River one mile south of where Martintown would later rise. Russell decided to call the place

Winslow after Edward Winslow, third governor of the Plymouth Colony and one of the Puritan leaders who

had journeyed aboard the Mayflower in 1620. In the 1830s in the northern half of

the United States, the Pilgrim Fathers were greatly revered figures, and Russell believed that prospective

settlers would be impressed by such an evocative and distinguished name.

Russell had no intention of remaining in Illinois any longer than he had to, but given how much B&WL money

was at stake -- the company’s commitment to Winslow had taken more of the consortium’s investment funds than

any single site within a portfolio that also included holdings in Missouri, Wisconsin Territory, and other

parts of Illinois -- he was prepared to personally stay in place, overseeing development, until he

could honestly report to his partners that all was going according to plan. He appears to have imagined

he would only have to make Winslow his home for a couple of years. Maybe three. He was not being realistic.

He was underestimating the amount of persistence and continued investment it was going to take to generate

a profit for B&WL -- or even, for that matter, avoid building up debt.

What Russell had been trying to do was “get in on the ground floor” and lay claim to property others would

soon want, but it took more than a catchy name to get anyone to want what they could have at Winslow. The

only improvements at the location when B&WL grabbed up its 1200 acres there consisted of a handful of log

cabins, the first built by George Lott in 1834, and a primitive sawmill erected in 1835 by Lott, brothers

Jere and Harvey Webster, and Hector Kneeland, and acquired in 1837 by Samuel Fretwell. This was not enough.

Prospective settlers didn’t want raw potential. They needed to see some infrastructure. Otherwise they

would pass by and settle elsewhere. Russell seems to have counted on some of that infrastructure “falling

into place on its own.” By 1838, he had come to understand that B&WL needed to goose the process.

First, Winslow needed to beat out its nearest competition. There were two rival centers of settlement

along that small stretch of the Pecatonica. From the site of Winslow the Pecatonica flowed east for a

mile and a quarter before turning south again. At that bend was Brewster’s Ferry, where Lyman

Brewster -- now regarded as the vicinity’s first white settler -- had established a ferry in 1833,

putting up a double log cabin home at the eastern mooring, devoting half of it to his living quarters

and setting up a general store in the other half. A mile and a half downstream (i.e. to the south) was

Ransomburg, established by Amherst C. Ransom in 1834. Neither was much of a mecca, but in 1838 both had

more going for them than Winslow, including higher existing populations. Brewster’s Ferry had not only

its store and ferry, but a post office. Ransomburg had a store, a tavern, and a schoolhouse.

Russell went looking for men to build commercial structures in order to provide Winslow with its

much-needed village core. He went to Galena, thirty-five miles to the west, a lead-mining center which

had been founded in the early 1820s. As far as the northwest corner of Illinois went, Galena was the only

true town already in existence. It was still small and still quite rustic, but it was established

enough that it was the prime spot where newly-arriving Easterners gathered in order to scope out the

region and find out where opportunities might lie. Russell found what he was looking for -- Morton

Thompson and Company, seven young men who had come to the West in order to go to the unexploited

forests of Wisconsin and set up a sawmill and either make a fortune from the resulting lumber, or

sell the operation for a fine price once it was up and running.

Morton Thompson and Company was a brand-new entity formed in the summer of 1838 back in Plymouth

County, MA. It was the brainchild of brothers Edwin and Freeman Morton, and brothers Ichabod, Columbus,

and Hiram Thompson. Just before heading west, they convinced two other men, a respected millwright

named John Bradford (1809-1893) and his friend (and former apprentice) Thomas Loring, to join their

venture. By the autumn of 1838 they had made it to Galena, only to be temporarily stranded there because

the water was too low for steamboats to proceed north, and because tales of hostile Indians in the region

to which they were heading made them want to wait until conditions sounded more secure. William Russell

sought them out, having heard of their expertise and the equipment they had brought. He convinced them to

abandon their original scheme and come to Winslow to remodel the Fretwell sawmill and put up a shingle

mill. Soon they were also erecting a blacksmith shop, a wheelwright shop, and a ten-bed hotel.

The Morton brothers and the Thompson brothers did not much enjoy their time in Winslow. They were often

sick. As Easterners, they were unaccustomed to frontier life and found it rougher than they had

expected. They left in 1839. The Mortons returned at once to Massachusetts. The Thompsons

headed back in the direction of Galena and founded a flour mill at Apple River. But Loring and

Bradford stayed, accepting a contract from Russell to build a flour mill. Loring would not leave Winslow

until 1846. Bradford continued to reside there for the rest of his long life.

When Bradford and Loring and the rest of Morton Thompson and Company arrived, they found Nathaniel and

Isaiah Martin already on site. The pair were living in a log cabin by the mill pond dam. Russell had

hired them to refurbish the dam, which the Webster brothers had first erected in 1835 across Indian

Creek, a tributary to the Pecatonica. The creation of a mill pond was absolutely essential because the

terrain around Winslow was so flat the river ran sluggishly, and to have power for a sawmill absolutely

required the creation of a mill race. The original dam had been a mixture of logs, stones, gravel, and

whatever else was near at hand. It had not held up. The Martin brothers did a better job -- among the

surviving papers of the Boston and Western Land Company is the 1839 contract between Russell and Winslow

locals William Penn Cox and Alvah Denton to increase the height of the mill pond dam so that the water

flow would generate enough power for the projected flour mill (and help out the sawmill, which had been

underpowered all along). Cox and Denton were instructed to meet the standard set by Nathaniel and Isaiah

when creating the smaller version of the dam in 1838. One of the bonuses Cox and Alvah received was three

months’ free housing in the log cabin that Nathaniel and Isaiah had just vacated.

It’s a fair question to ask why Isaiah and Nathaniel, who had done satisfactory work on the dam in 1838,

weren’t given the 1839 contract to make it higher. The answer appears to be timing. Back in the spring of

1838, neighbor Calvin Hoffman, future son-in-law of the aforementioned William P. Cox and a young man of

Nathaniel and Isaiah’s generation -- Calvin was just nine weeks younger than Nathaniel -- had finished

building a boat at the Winslow mill and began using it to transport goods. Nathaniel went along with

Calvin and his relative (probably brother) James Hoffman on the second 1838 voyage, helping take a load

of lead produced by the Hamilton mining company of Lafayette County down to St. Louis. This same tandem

repeated the trip in the summer of 1939 and would do so again in the summer of 1840. It’s hardly

surprising why Nathaniel would have preferred to crew a trading run than rebuild a dam. Expeditions of

that sort had the potential for substantial profits -- the way down was paid by Hamilton, leaving the

boat able to bring all sorts of cargo back north to a wide variety of customers. River transport was

critical to the movement of goods in the region at that time. Railroad lines had not yet arrived in the

northwestern corner of Illinois, and there were few proper drayage roads, few bridges, few inns and stables

at which to stop and refresh both humans and beasts of burden. Besides, going along on the boat meant

Nathaniel got to see new places and meet new people. Work as a laborer in Winslow was always there as a

wintertime occupation when snow and river ice confined him to home.

How much work Nathaniel did for B&WL in the late 1830s and early 1840s is not perfectly clear, but there

is no doubt he was an employee (or contractee) they valued, even if his intervals of employment were

sporadic. Now that the sawmill was remodelled and would soon have better power capacity, it

was time to get some lumber cut. B&WL hadn’t managed to make money yet by selling land. Meanwhile they

had taxes to pay on their acreage. (Recall that in the 1830s, the government did not run on payroll taxes;

it depended heavily on property taxes, and those could be burdensome.) Another critical reason to get

timber harvested and put into the form of saleable lumber was to thwart the poaching of the best trees.

These factors set up a situation in which Nathaniel and Isaiah’s skill set was perfect. They had come from

mill country. They knew how to identify the best timber and how to get it transported and, if need be,

could also put in hours at the mill as sawyers. The Martin brothers now had enough assurance of

money-earning opportunities that they resisted the lure of longterm possibilities elsewhere. Winslow was

home to both of them for the remainder of the 1840s.

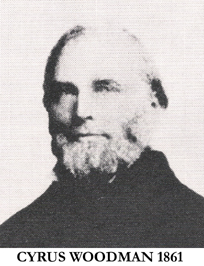

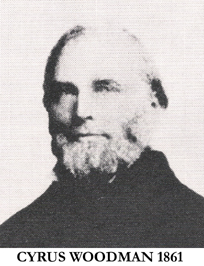

At the beginning of 1840, William Russell returned from a trip

back East where he had gone to meet with his partners. He was accompanied back west by a new assistant,

Cyrus Woodman, a twenty-five-year-old Boston attorney. Cyrus would not return to New England until decades

later, and he would make Winslow his home until 1845. Not long after his arrival he persuaded Charlotte

Flint, a young woman of his acquaintance, to become his wife. Their log cabin in Winslow was where their first

children were born. This is another way of saying that Cyrus understood as soon as he arrived that to do

his job right, he would have to stay a while. William Russell had made a mess of things -- not only because

he had been too optimistic about the investment, but because he was characteristically disorganized. His

lack of competence in handling fairly routine aspects of land transactions and debt collection (and debt

payment, including payment of taxes) had jeopardized the good will of clients, business associates, and the

government. Even people with whom he had a good relationship had reason to be annoyed with him. Bradford

and Loring, for example, could not have taken the news well that there was insufficient money left to pay

them as much as promised for establishing the flour mill, the B&WL partners having declined to pony up more

than the $14,000 Russell had already spent at Winslow. For what it was worth, Russell was not a con artist.

He had genuinely wanted and expected the Winslow project to succeed. He just wasn’t the man to get the job

done. By this point, he was fully aware of that. The stress and worry had ruined his health. He was on the

verge of exhaustion. Cyrus was the opposite sort -- level-headed, hard-working, scrupulously honest, and

brimming with the energy of youth and health. In the summer of 1840, Russell retired and went back East to

recuperate, leaving Cyrus to operate the land agency alone. After a five-month apprenticeship, Cyrus was

already better at the job than Russell had ever been.

At the beginning of 1840, William Russell returned from a trip

back East where he had gone to meet with his partners. He was accompanied back west by a new assistant,

Cyrus Woodman, a twenty-five-year-old Boston attorney. Cyrus would not return to New England until decades

later, and he would make Winslow his home until 1845. Not long after his arrival he persuaded Charlotte

Flint, a young woman of his acquaintance, to become his wife. Their log cabin in Winslow was where their first

children were born. This is another way of saying that Cyrus understood as soon as he arrived that to do

his job right, he would have to stay a while. William Russell had made a mess of things -- not only because

he had been too optimistic about the investment, but because he was characteristically disorganized. His

lack of competence in handling fairly routine aspects of land transactions and debt collection (and debt

payment, including payment of taxes) had jeopardized the good will of clients, business associates, and the

government. Even people with whom he had a good relationship had reason to be annoyed with him. Bradford

and Loring, for example, could not have taken the news well that there was insufficient money left to pay

them as much as promised for establishing the flour mill, the B&WL partners having declined to pony up more

than the $14,000 Russell had already spent at Winslow. For what it was worth, Russell was not a con artist.

He had genuinely wanted and expected the Winslow project to succeed. He just wasn’t the man to get the job

done. By this point, he was fully aware of that. The stress and worry had ruined his health. He was on the

verge of exhaustion. Cyrus was the opposite sort -- level-headed, hard-working, scrupulously honest, and

brimming with the energy of youth and health. In the summer of 1840, Russell retired and went back East to

recuperate, leaving Cyrus to operate the land agency alone. After a five-month apprenticeship, Cyrus was

already better at the job than Russell had ever been.

Cyrus quickly fixed a number of organizational problems within the agency and saved the reputation of B&WL

among the locals, including talking Bradford and Loring into accepting, in lieu of cash, a lease on

the mills free of charge for the time being. (The arrangement would eventually evolve into ownership.)

Cyrus was also quick to recognize that he must continue to follow in Russell’s footsteps and find ways

to transform Winslow into an attractive place to live. To better manage the hotel, in the spring of 1840

Cyrus leased the hotel to Daniel Sanford, who had experience running a tavern north of Freeport. Sanford’s

one-year tenure was financially successful, but Cyrus felt he could do even better, and on 1 May 1841,

shifted the lease to Nelson Wait. Cyrus declared in a 20 July 1841 letter that under Wait’s management

the hotel was now “better kept than it has been since it was opened.” There

was no school yet, and while it was not yet possible to build an actual schoolhouse, classes could still

be held. Daniel Sanford’s nineteen-year-old sister-in-law Hannah Hammond was tapped to be the teacher of

the first term, held in 1841 in the wagon shop of Edward Hunt. In June, 1841, Cyrus donated

a B&WL home lot in Winslow to Hannah’s brother-in-law William Shortreed so that he could build and open a

general store. Cyrus also encouraged, designed, and sometimes contributed company funds toward vital

infrastructural improvements. One of the most essential was better drainage. Winslow was low-lying and was

right on the banks of the Pecatonica and a number of its feeder creeks. Malarial mosquitoes

were rampant. Quite a number of residents perished of malaria or other swamp-related fevers in the early

1840s, one victim being Cyrus and Charlotte’s baby son, Frank.

Ingenious and hard-working as Cyrus was, he could do little for quite some time to resolve the main problem

he had been sent to deal with -- he needed to sell land. But for the first three to four years of his

Winslow tenure, the nation was going through economic contortions, one of the side effects being that cash

was in extremely short supply on the frontier. Quite a number of settlers had arrived, but they could not

afford to buy title to the land they were clearing and farming. They didn’t have the dollars and cents.

Locally they were able to make do by subsistence farming and hunting and by bartering goods or services,

but the Boston capitalists (and the government) wanted real money before they would hand over official

deeds. Meanwhile, B&WL had bills to pay -- taxes, Cyrus’s salary, capital improvements, etc. -- so for

years to come exploitation of timber remained an essential part of what Cyrus did for the forty-three

partners, at first as a group and then, when B&WL was split up, for individuals who had acquired portions

of the original portfolio. This was no easy task. Few people had money to buy lumber and so the mills

could not operate consistently -- eventually the stacks of unsold lumber were as high as there was room

for, and Bradford & Loring saw no point in operating full-time. Yet if the timber did not get harvested,

poaching in the forests would continue until nothing of value was left on a given parcel. Just getting the

timber surveyed and then guarding it was the best Cyrus could do, but here he faced another

dilemma -- very few local men were available to conduct those surveys, and few were honest enough to report

back accurately, the temptation being to fudge the figures and then conduct a little poaching of their own,

a “fox guarding the henhouse” scenario. Cyrus soon came to realize he could trust the Martin brothers. And

so began a relationship that would have a profound effect on the destiny of Nathaniel Martin. As Cyrus and

Nathaniel continued to work together over the next quarter of a century, they came to greatly admire one

another and would remain friends until death. Nathaniel might well have never become so prominent as to be

the subject of the 1901 biographical sketch had it not been for Cyrus’s positive influence and support.

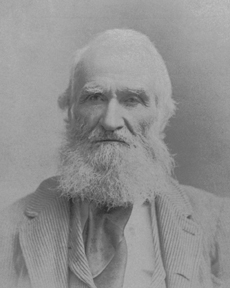

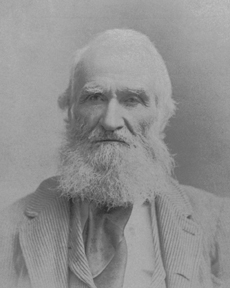

Moreover, if not for Cyrus Woodman (shown at right),

we would today know very little about Nathaniel’s twenties and early thirties beyond “for several years

he worked at day wages.” Cyrus understood that history is encapsulated in the written material left behind

after those who lived through a given period have passed away. Accordingly, he kept every letter sent to

him from about 1840 onward, and by the mid-1840s he began keeping copies of his outgoing letters as well.

He had the correspondence bound into durable volumes and eventually donated it all to the Wisconsin State

Historical Society, an institution he helped found after he and Charlotte had moved to Mineral Point, WI.

The volumes now make up a large part of the Cyrus Woodman Papers collection at the University of Wisconsin

in Madison. Within that trove are many letters written to, received from, or that mention Nathaniel and/or

Isaiah Martin. The letters Nathaniel sent to Cyrus represent the only examples of Nathaniel’s writings

that survive aside from his signature on legal documents such as deeds. This circumstance is somewhat

surprising. As mentioned above, Nathaniel was a literate man. His letters in the Woodman Papers show he

had an admirable command of spelling, grammar, and diction, and a poetic manner of expressing himself. He

must have written a great many pieces of correspondence in his day, yet none appear to have been saved by

any of his descendants. Fortunately Cyrus was more concerned about posterity than was the Martin clan.

Moreover, if not for Cyrus Woodman (shown at right),

we would today know very little about Nathaniel’s twenties and early thirties beyond “for several years

he worked at day wages.” Cyrus understood that history is encapsulated in the written material left behind

after those who lived through a given period have passed away. Accordingly, he kept every letter sent to

him from about 1840 onward, and by the mid-1840s he began keeping copies of his outgoing letters as well.

He had the correspondence bound into durable volumes and eventually donated it all to the Wisconsin State

Historical Society, an institution he helped found after he and Charlotte had moved to Mineral Point, WI.

The volumes now make up a large part of the Cyrus Woodman Papers collection at the University of Wisconsin

in Madison. Within that trove are many letters written to, received from, or that mention Nathaniel and/or

Isaiah Martin. The letters Nathaniel sent to Cyrus represent the only examples of Nathaniel’s writings

that survive aside from his signature on legal documents such as deeds. This circumstance is somewhat

surprising. As mentioned above, Nathaniel was a literate man. His letters in the Woodman Papers show he

had an admirable command of spelling, grammar, and diction, and a poetic manner of expressing himself. He

must have written a great many pieces of correspondence in his day, yet none appear to have been saved by

any of his descendants. Fortunately Cyrus was more concerned about posterity than was the Martin clan.

It is from the letters that we can be sure Nathaniel and Isaiah surveyed timber lands. When the 1901

sketch refers to Nathaniel having “chopped wood” for one winter in St. Louis, it is unlikely that he was

just chopping firewood. He and Isaiah were probably selecting and cutting trees for a sawmill owner.

William Russell’s confidence in their abilities was probably formed at this time by virtue of having seen

them in action, or by speaking to their St. Louis employer(s). As the 1840s went on, Cyrus continued to

hire Nathaniel and Isaiah again and again, not just as scouts but as woodcrafters, calling upon them to

produce a variety of lumber products from shingles to railroad ties to bedsteads. This in turn strongly

implies the Martin boys did a great deal of work at Bradford & Loring’s sawmill -- though later in the

1840s they did have an alternate option, the Wickwire sawmill near the site of Brewster’s Ferry. Whether

they worked for themselves by leasing Bradford & Loring’s equipment, or served as Bradford & Loring’s

intermediaries with Cyrus, is not possible to discern from the surviving material.

Back in 1842, if someone had told Cyrus and Nathaniel they would have such a long-lasting relationship as

both business associates and friends, they might not have predicted it. That was a year that tested the

good will of both men toward one another. Things began with bright hopes, though. Having become experienced

at river trading, Nathaniel saw an opportunity to move up in the world. His former boss and partner

Calvin Hoffman was now a

married man. Calvin needed to stay put rather than head off and leave his pregnant wife on her own.

Nathaniel, teaming up with Isaiah, built a keel boat at the Winslow mill, hiring Job Churchill (an early

Winslow settler, and the original proprietor of the hotel) to serve as carpenter. This gave Nathaniel

the means to fulfill the Hoffman 1842 summer contract to take Hamilton Company lead down to St. Louis,

James Hoffman and Abe Hoffman taking Calvin’s place. On the trip north, they ventured well up the Des

Moines River into Iowa on behalf of other customers.

During that summer trip, Nathaniel was obliged to partner up with the Hoffmans due to their established

relationship with the mining company. For other trips, Nathaniel and Isaiah were the men in charge. They

took along three others as their crew. A letter in the Cyrus Woodman Papers specifically refers to a

trip made in the late spring and another in the early autumn of 1842. The author of the letter was

Samuel Fletcher Flint, a brother of Cyrus’s wife. Fletch, as he was known, came to Winslow when Charlotte

was a young bride in order to help her with the transition from being an Eastern lady of genteel

circumstances to a young mother living in a log cabin on the edge of civilization. Fletch was one of the

three men who served as Nathaniel and Isaiah’s crew, another being Joseph Hicks and the other a man whose

name Fletch could not recall when he dictated the letter to his wife in 1881 in answer to questions posed by

Cyrus, who had agreed to contribute material to a history of early Winslow being written by Thomas Loring.

Below is Fletch’s description of the autumn voyage:

“Found plenty of game and good fishing. Had a sail to help when the wind was favorable. One

day having caught a barrel of fish with spears and having no salt, the boat was moored where a man

was seen putting out flax to rot. He was a Dutchman and we made him a present of the fish, at first

he was fearful he would be expected to pay for them, but when he understood it he begged us to wait

till he could go to his house. He soon returned with five gallons of whiskey on a wheelbarrow which

was presented to the boat. The water was very low and the boat frequently got aground, and when

that happened, potatoes enough were sold to float us again. Sometimes we were obliged to sell for

six cents per bushel, a Keokuk having sold the cargo. The boat was sold for town lots which became

very valuable, but as the taxes were never paid the owners got nothing. The voyage was a long one

the wind being upstream and the beam low. One night with a fair wind we raced with a steamboat. When

the wind was fair we would beat the steamer, but then an unfavorable turn in the river would beat

us. Caught a sturgeon 4 ft 8 in long.”

Whether there were more than three total voyages is not addressed by Fletch’s material. He left for

Massachusetts soon after the boat returned to Winslow and would not have been available to crew any

further. But his comment “The boat was sold for town lots” is extremely revealing, especially when

it is put together with one of Cyrus’s letters to Nathaniel written in 1842 in which Cyrus threatened

legal action unless Nathaniel paid a debt. From that indirect evidence, it would appear B&WL had

loaned or otherwise advanced Nathaniel and Isaiah money to construct the keel boat and one or more

payment(s) on that investment had become overdue. Despite how patient he could be in other respects,

Cyrus was virtually incapable

of letting a month go by without dunning a person for a debt owed, even when he knew perfectly well

the reason was not a deficiency of character but strictly a matter of a profoundly empty wallet. So

what happened? Why didn’t Nathaniel and Isaiah earn as much as they expected from their expeditions?

The answer surely has to do with the price of flour that year. The Winslow flour mill had been up and

running in 1841 and had enjoyed a windfall of profit. When Nathaniel and Isaiah had decided to build

their boat, undoubtedly they imagined they would be able to transport sack after sack of flour up and

down the Pecatonica and find scads of customers willing to pay similarly high prices. But the price

of flour plummetted in 1842. Bad news for the Martin brothers. It was even worse news for Cyrus

Woodman and B&WL, who did not get the big payments they expected from Bradford and Loring and were

left scrambling to try to make up the difference -- hence Cyrus’s impatience and his intemperate

demands. He and the Martins must have worked it out by arranging for B&WL to buy the keel boat. It was

worth more than the debt. However, Cyrus faced the same dilemma as the Martins, which was that he had

no cash to spare. So he paid in town lots. These potentially represented more worth than what was owed

for the boat, but everyone realized the land would not actually have much value at all unless the

economy shifted in a timely manner and people started paying for deeds. Alas, it did not shift that

fast. Nathaniel and Isaiah had to hang on to the properties too long, until the unpaid property tax

burden was greater than the market price.

One factor that ruined everyone’s optimism was that 1843 was another terrible year. A lack of rain

left the mill pond too low to operate the water wheels at either the sawmill or the flour mill. As a

result, nearly everyone in

Winslow would have been poorer at the end of the year than at the beginning. But things got better as

the decade progressed -- good enough that Nathaniel and Isaiah stayed put.

The fact that Cyrus once dunned Nathaniel for a debt is ironic, because a letter from Nathaniel to

Cyrus Woodman written 18 March 1847 reveals Nathaniel was from time to time

recruited by Cyrus to try to collect debts owed by other Winslow residents. By 1847, Cyrus and Charlotte

and their youngsters were living in Mineral Point, twenty-five miles to the northwest. Cyrus was still

doing a substantial amount of Winslow-related business, though -- some of it on behalf of himself and

Eastern property holders who owned portions of the now-defunct B&WL, and some on behalf of locals who

knew he was the right man to process deeds and arrange mortgages. Cyrus was growing

concerned about the mortgage debt owed by Cornelia Kneeland. Cornelia and her brother Charles H.

Kneeland had acquired the ten-bed hotel from B&WL in 1843 and had run it together during the mid-1840s,

but Charles had died at the beginning of 1847, leaving Cornelia in an unsettled set of circumstances.

Nathaniel comments that he “had upon reflection decided not to do anything” about the matter of payment

because he had spoken to Cornelia and she thought she “had better pay up the mortgage as it will be lip

service in the end” -- i.e. it would affect her reputation. And it was quite the reputation. Thomas

Loring thought her so incredible he wrote in his Winslow history of their first enounter in Galena in

1838: “There for the first time we saw the Queen of the West.” The problem of the debt was soon resolved

when Cornelia’s sister Sarah and brother-in-law Joseph Rogers Berry bought the hotel. They ran it until

Sarah’s death in 1854, during which time it was called Berry House. (It is unclear if the establishment

had any name other than “the hotel” until then. After the Civil War its incoming proprietor William

Brady named it the American House. When Henry and Harriett Chawgo took over from Brady in 1875, they

called it Chawgo House. The hotel remained a major fixture of Winslow until 1902, when a huge fire

consumed it along with most of the other commercial downtown structures.)

The timber-scout occupation surely accounts for Nathaniel meeting Hannah Strader. Hannah and her family

had arrived in Stephenson County at about the same time as Nathaniel, i.e. about 1837, and had settled

in a spot near the present-day community of Waddams Grove, a half a dozen miles southwest of Winslow.

Hannah had turned eight

years of age in the summer of 1837. She would be about sixteen when she and her family moved on to

Jordan Township, Green County, WI in approximately 1845. During those eight years, the Straders were

residents of the area then known as Richland Timber. This obsolete place name apparently refers to a

particularly fine stretch of timberland that extended through western Stephenson County

up into Green County. It was precisely the sort of region where Nathaniel would come to look at and/or

harvest trees for Cyrus Woodman or for Bradford & Loring. While there, he would often have been too far

afield to make it home to Winslow every night. Given the lack of inns and hotels, he would have

paid local settlers to provide a bed and meals while he was working nearby. Hannah was not quite old

enough to woo at the time, but she clearly made such a good impression on him that he went to court her

up in Green County after she turned seventeen, considered in those days to be a prime age for a female

to become a wife.

Nathaniel was apparently something of a dream come true for Hannah. The Straders were part of a

religiously like-minded group of families that had tied their fates together for generations from the

beginning of the 1700s to the mid-1800s, moving en masse from the Rhine Valley of Germany to the

Netherlands to Guilford, NC to Preble County, OH to Vermilion County, IL and finally to the Pecatonia

River area. Often members of a given generation of Hannah’s ancestors had married members of the same

neighboring family. This pattern was being maintained even in Green County. Ultimately three of Hannah’s

sisters married sons of James Frame and Susannah Bradshaw. Hannah was being urged to marry Thomas Frame,

another son of that family. If she had done so, she would have been embedded in an interwoven set of

households and would have remained under the day-to-day scrutiny of her parents. Hannah clearly craved

greater independence than that, and wanted a mate who was more than just another farm boy

of a family she knew so well it must have seemed stifling to consider marrying into. So she chose

Nathaniel. The couple were married at Jordan Center -- the crossroads in the midst of Jordan Township,

never an incorporated place and one that ceased to exist by the end of the pioneer era -- by John

Kennedy, a local justice of the peace. For the rest of his life, Nathaniel is said to have chuckled out

loud whenever the matter came up of Hannah “almost” marrying Thomas Frame.

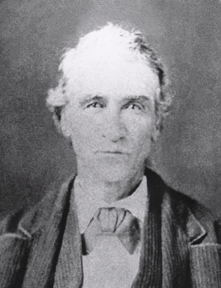

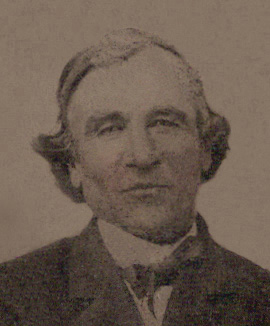

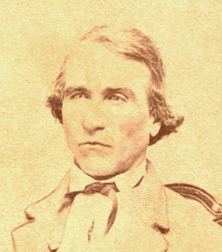

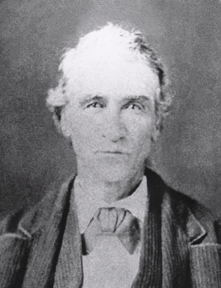

This is the only portrait available of Nathaniel Martin and Hannah Strader posing together. This was

scanned from one of the several tintypes made at the time of the original photography session. A tintype,

also known as a ferrotype, consists of a positive image etched onto a metal plate. This sort of

photography became widely used beginning in the mid-1850s and remained the standard until the mid-1880s,

when it was supplanted by film-negative photography. (The absence of smiles in ferrotypes is because

they required the subject to remain motionless

for forty-five seconds or more, too long to maintain a steady smile.) Crude though the photographic

industry was back then, the method could capture fine detail in the hands of a professional. This

one has suffered some corrosion as tintypes often do over time, but it still retains an astonishing

fidelity considering that the original is only two inches tall by one-and-a-half inches wide. (You

will not be able to appreciate that fidelity through your web browser, of course. It would be quickly

apparent if you had the full-resolution version of the scan in your computer and kept hitting the

magnification tab.) Judging by their apparent ages,

Nathaniel and Hannah probably sat for this picture in the mid to late 1860s. It resembles the wedding

portrait photograph of their daughter Nellie and her bridegroom John Warner, taken in 1869. (The other

photos of Nathaniel on this page, with the exception of the one of him in his eighties, were also

tintypes to begin with, but the scans for this website were made from prints created at various points

over the decades; unfortunately that means not all detail was preserved.)

Nathaniel and Hannah settled at first in Winslow. Children began arriving at once and would continue

appearing at a steady clip. Elias was the first child, born in early 1848 about eleven months after the

wedding, then came twins Nellie and Alice, the latter of whom sadly died at less than five months of

age. Winslow was still in a primitive phase but was growing steadily. Some people were even living in

wood-frame houses now rather than log cabins. (The first frame house had been thrown up by Samuel

Fretwell. The next -- a truly fine “built to last” dwelling that remains standing to this day -- was

constructed by Bradford and Loring

early in their tenure and went on to be the long-term residence of the Bradford family.) Cyrus and

Nathaniel, along with Isaiah, no doubt found plenty of work producing lumber and

other finished goods from the wood they cut, as described above. Yet both brothers were still mostly

just laborers, still in search of lasting means of prosperity.

The year 1850 proved to be the critical turning point. Despite what was said in the 1901 biographical

sketch, Nathaniel was by no means the originator of the plan to dam the Pecatonica at the state line

and build a sawmill there. It was yet another of Cyrus Woodman’s schemes. Cyrus represented the

owners of the water rights to that section of the river, and knew that to get the full value for those

rights, the water power needed to be developed. In 1848, Cyrus convinced a man named Edwin Hanchett to

establish a sawmill there. Naturally Hanchett needed to build a dam first -- the Pecatonica was as slow

there as it was at Winslow. Given Nathaniel and Isaiah’s experience with dam-building, they were

natural people to hire to do the work, yet in fact it is unconfirmed that Isaiah worked on the project

at all, and even Nathaniel may not have been involved at the very beginning, though certainly he was

involved early enough that he was credited in the 1901 sketch as having “built a dam on the Pecatonica

River.” However, in the early stages of the project, he was a laborer, not an owner. Hanchett was in

charge, and by 1849 had started work on the mill itself. Nathaniel must have helped build the structure

and install equipment. He is described in the 1850 census as a

lumberman. His role was significant enough that he had by then seen fit to relocate the family,

putting up a house at what would soon become the village of Martin (but was at that point officially

just a corner of Cadiz Township). The move occurred some time between the late spring of 1849 and the

late spring of 1850 because the twins are known to have been born in Winslow 11 May 1849, while the

census, dated 1 June 1850, shows the family at their new home.

By early 1850, the construction project was foundering. Hanchett must have run out of funds, or realized

he had been overoptimistic about what it would take to get the mill up and running. He may simply have

lacked the expertise to complete the venture. Cyrus Woodman was not to be thwarted. He knew people back in

Boston who might serve as “venture capitalists.” But Cyrus doubted that Edwin Hanchett was the man to

impress these potential investors. Nathaniel Martin, on the other hand, possessed the charm, intelligence,

honesty, and competence as a sawmill man to pull off the trick. The catch was, Nathaniel had to show up in

person and shake the appropriate hands.

At this point in time, Wisconsin, along with the rest of the western edge of the settled part

of the United States, was rapidly emptying out of able-bodied men. Gold fever had struck. Thousands

had headed and were still heading to California. Isaiah Martin was one of those who would succumb to

the lure. He and about sixty other Winslow-area men left on their journey in late May or early June,

1850. This proved to have overwhelming consequences for Isaiah. For the first time, Isaiah was forging

a destiny separate from Nathaniel, and as it turned out, it was

precisely when Nathaniel would launch on a path of incredible and lasting success. Isaiah would

probably have shared that success as a full partner, given the brothers’ pattern until then. Instead,

Isaiah spent a largely fruitless period out West and returned having fared no better than break-even,

if that much. Among other losses, his absence meant he was deprived of nearly all the opportunity he

would ever have to hold

his son James T. Martin, who was only weeks old when Isaiah left and who subsequently died in infancy.

Cyrus Woodman doubted the potential of the Gold Rush, but the exodus of people from Wisconsin was

depressing his land-agency business, and he felt obliged to at least check out the possibilities for

himself. He made enough arrangements that he knew he would at least be able to re-coup the cost of

the expedition, and by May of 1850 was on his way, heading first to Boston and New York to

see his brothers, then travelling by steamer to the Isthmus of Panama. He would spend about six weeks in

Sacramento trying to drum up business. He saw potential, but realized he would have to spend several

years bolstering his client base. He figured he would not only be more comfortable back in Wisconsin,

but in the long run would probably make more money, so back he came.

When Cyrus went East, Nathaniel went with him. How Hannah coped with her spouse’s absence is

unknown -- she had toddlers Elias and Nellie to care for, and had recently become pregnant with what

would be the couple’s fourth child, Jennie Edith Martin. Cyrus familiarized Nathaniel with Boston and

then proceeded on to New York to await the departure of his ship. Nathaniel remained with Cyrus’s brother

Horatio Woodman, an attorney best recalled today as an editor of some of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s essays.

Horatio completed the process of introducing Nathaniel to the “right people.” The latter were indeed

impressed by Nathaniel, just as Cyrus had hoped. Nathaniel headed home with the means to take over

where Hanchett had failed. Ultimately he would regard Horatio’s role in his fortunes with such favor

he would name his next son Horatio Woodman Martin.

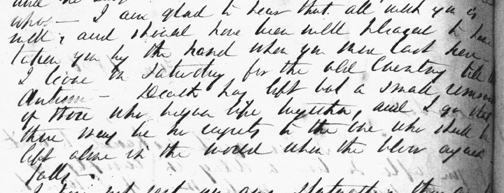

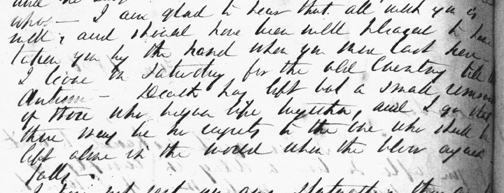

One of the best examples of Nathaniel’s means of expressing himself is his 6 June 1850 letter to Cyrus,

written in Boston three days after Cyrus had departed for New York. The letter ended up being sent to

Cyrus’s home in Mineral Point, and Cyrus did not actually read it until December, 1850, but it remained

in his papers and the original is now in the history room of the library at the University of Wisconsin

in Madison. Below is one paragraph in which Nathaniel laments not having said a better farewell to Cyrus.

They parted with the knowledge they might never see one another again, given that Cyrus was to stay an

indefinite interval, and given that his journey involved a certain amount of peril. Nathaniel waxed on

for a line or so about mortality and the value of comrades with whom one shares the road of life.

I should have been well pleased to have taken you by the hand when you were last here. I leave Saturday

for the old country like Antrim. Death has left but a small answer of those who travel life together, and

I vow that there may be no regrets to the one who may be left alone in the world when the blow always

falls.

(It must be said that Nathaniel’s penmanship was such that a couple of the words in this transcript are

guesses. A scan of that section of the actual letter is shown below.)

Hanchett stayed on as partner long enough to see the sawmill completed and then operated it with

Nathaniel for a year. From 1851 onward, Nathaniel was the principal owner. Given how well the business

did through the 1850s, the money men were probably paid off sooner rather than later, and everyone who

had committed in some way to the project in 1850 appears to have been happy with the results, even

Hanchett, who if Nathaniel had not rescued him might never have ended up with anything for his early

efforts. Hanchett’s place was taken by Isaiah, who had returned from California. The Martin brothers

became a team again, and Isaiah deserves full credit for much of the initial growth that put the village

on the map. It was no doubt because his brother was available to keep the sawmill going smoothly that

Nathaniel could proceed with the building of a flour mill in 1854, and then began to contemplate adding

a woolen mill. During these years Isaiah may have been a co-owner -- certainly he is described as having

been Nathaniel’s partner -- but he was subordinate to Nathaniel. This probably rankled him to at least a

small degree, given that Nathaniel was the younger brother, but there was no getting around the fact

that when someone was needed to step into the leadership role and win the confidence of the investors,

Nathaniel had been The Man, whereas Isaiah had been off chasing get-rich-quick dreams. The difference

between the two siblings could probably be summed up no better than by the divergence in their choices

in 1850. Nathaniel had done well by himself and Hannah and he held on to his reward -- which was primary

ownership and final-word control -- even while exhibiting his usual generosity and welcoming his brother

back to play a big role.

And not just one brother. Things were now going so well that quite a number of members of the Martin

clan turned up. By the middle of the 1850s the village of Martin or the nearby communities

of Winslow or Nora, IL became home to his younger siblings Nancy Mew, Rebecca Burwell, and Charles

Alexander Martin, as well as to his elderly parents, James and Rebecca. It was in Martin that James

passed away in the autumn of 1856, to be buried in the family graveyard on the hilltop overlooking the

mills. That was the year a proper bridge was completed across the Pecatonica, uniting the mills with

the Winslow side of the river. This is probably also the point when Nathaniel completed the fine big white

house he and Hannah would live in for the remainder of their days. The original residence was one story

tall and had been constructed quickly of basswood (linden) lumber -- the local equivalent of cheap pine.

The exterior had not even been painted. The place was sub-standard and now too small given that the

Martins were now up to five living children. (It would have been seven had Alice not perished in 1849 and

had William not died at birth in 1854.) They needed the room, so up went a fine two-story replacement

of materials worthy of the family’s prosperity. A newspaper article written in the late 1800s reminiscing

about Martintown and Winslow as they were in the mid-1850s reveals that the new structure was erected a

slight distance downhill from its predecessor. Once the bigger place was completed, it was often home to

additional family members including the aforementioned Charles Martin, Nathaniel’s nephew William Burwell,

and Hannah’s younger brother Daniel Strader, all of whom were still bachelors. The permanent schoolhouse

(which still stands) was probably erected about then as well, replacing the first school, a

twelve-foot-by-twelve-foot square hut where Belle Bradford, daughter of John, taught the first terms. The

hut had been adequate for the initial group of students, who appear to have consisted of only the eldest

few Martin children and the eldest offspring of local gunsmith Tracy Lockman, but now there were more

families in the village with children of school age. Inasmuch as the bridge afforded a safe and convenient

means for little Elias, Nellie, and Jennie Martin to cross the river, the new schoolhouse was constructed

on the south side of the river, something which became true of nearly all the subsequent structures built

in the village.

Circumstances were so good that Nathaniel turned down an opportunity in 1855 to be a part of yet another

Cyrus Woodman venture. Cyrus had acquired timber lands and timber rights along the Kickapoo River of

Wisconsin and wanted

someone competent and trustworthy to build a sawmill there and get it going. He had been unable to find

anyone suitable and extended a plea to Nathaniel, even though Nathaniel was well set. After Nathaniel said

no, Cyrus made the same overture to Isaiah and was again met with rejection. In the end, Cyrus was

never able to find the right man and ended up selling off the Kickapoo River holdings without realizing

the profit that would have come had he been able to fully exploit the timber. It was a mark of Cyrus’s

desperation that he even made the overtures to the Martins at all, because he had ample reason to want

them to stay in place. One brother or the other (usually Nathaniel) had often been and were continuing

to be the delegates he depended upon to “look in on” properties Cyrus owned or represented in Stephenson

County or Green County. On many occasions Nathaniel and/or Isaiah would arrange to harvest and mill the wood

from those lands, and in return Cyrus would pay them in cash, in land, in a portion of the lumber, or by

the forgiving of debts they owed. Turning Cyrus down

concerning the Kickapoo River opportunity was only one example of Nathaniel’s level-headedness. He was

not afraid to “do business,” but he made sure not to over-extend himself. A letter by him to Cyrus dated

18 April 1856 has him choosing not to purchase nearby land Cyrus had offered in order to free up some

capital Cyrus needed for other purposes, and simultaneously backing out of a proposal to open a wagon

shop in Martin in tandem with John Bradford. (Such a shop was soon established, but it was operated by

Frank Lueck and it is not clear if Bradford was involved in the financing.)

The surge of prosperity finally slowed in 1857, no doubt due to the effects of the so-called Bank Panic

of 1857, which developed in the autumn of that year. The nation did not fully shake off the slow-down until

the early 1860s. Yet things were going so well in the village of Martin in 1855 and 1856 (aside from such

bits of misfortune as the death of James Martin) that it is almost difficult to imagine that by early 1858,

Nathaniel would experience one of the most troubling and alarming periods of his whole life: He literally

went crazy.

Naturally, no family likes to talk about its members going nuts, particular back then, and the Martin clan

was no exception. Nathaniel was a beloved figure and it is apparent that when he was not crazy, he

was not just a solid fellow, but the sort of person others wished they could be. So the family did not

speak of his problem in later years. By the the middle of the Twentieth Century when all of his children

and the eldest of his grandchildren were dead, there was no one left to tell the tale. Because of that

reticence, it is impossible to know all the particulars of what went on.

His insanity is one of the big mysteries about Nathaniel Martin. There is no doubt, though, that on at

least three occasions, he really was mentally and emotionally altered in a severe way.

The skeleton in the closet began to come to light in 1972. By then, Howard Frame of Porterville, CA, a

descendant of Hannah’s sister Elizabeth Strader Frame, was engaged in sustained research into the history

of the Strader and Frame lineages. One of the correspondents he enlisted in this effort was Mildred

Yeazel, who believed that her husband Ralph William Yeazel’s great great grandmother Sophia Strader

belonged to the same clan of Straders to which Hannah belonged. (Mildred was uncertain of her hunch at

the time, but in fact she was correct. Sophia Strader Yeazel was a first cousin of Hannah’s grandfather

Daniel Strader -- and as it happens, Sophia spent the last years of her life residing a few miles north

of Martintown.) Howard preferred not to leave California, but Mildred, a former Green County resident still

based in southern Wisconsin, was not so logistically challenged. And a good thing, too, because in those

pre-internet days genealogical discoveries often depended upon physical travel to vital statistics bureaus

in the counties where given relatives had dwelled. Mildred visited the Green County courthouse in 1972 and

unearthed the transcripts of three court hearings involving Nathaniel Martin’s mental competency. It is

clear from context that on each of those occasions, the petitioners had good reason to want a judge to

step in.

The first instance is noted in Green County Court File 229. On 18 January 1858, Nathaniel’s new

stepfather, Lewis John Enger (also known as Anger and as Johnson, and rendered as Engert in the

court transcript), filed a protest of the guardianship of Nathaniel apparently

previously granted to Nathaniel’s brother-in-law, Jeremiah Frame, husband of the aforementioned

Elizabeth Strader. Enger wanted himself appointed. Nathaniel’s brother-in-law John Burwell (name

rendered as McBurwell in the court transcript and likewise misspelled as Burrell in the 1901

commemorative sketch) similarly argued that Jeremiah Frame was not suitable because Jerry (as he was

known to the family) had no business experience. John B. suggested that Daniel

Gaylord of Stephenson County be tapped to serve. The latter, though it does not say so in the

transcript, was an attorney based in Winslow. John and Rebecca Burwell were then residents of

Winslow and had come to know Daniel Gaylord, accounting for their confidence in him. All in all

Daniel Gaylord was not a bad candidate, as he was no doubt well acquainted with Nathaniel.

The need for a guardianship was apparently little in dispute. Yet another brother-in-law, Daniel

Strader, who lived with Nathaniel and Hannah, testified as to what he had witnessed at the family

home. As rendered in abbreviated sentences by the court recorder, Daniel said of Nathaniel:

breaks up chairs and threatens to kill

had to rope him to keep him from harming

threw himself on floor, where he slept and laughed wildly

soiled clothing frequently

used very profane language

had to be chained

tore off all clothes and went about naked

took up the carpet and tore it

Jerry Frame retained guardianship in a decision rendered 20 January 1858.

The 1858 incident would not be the only one. Nathaniel seems to have been able to hold his own through

the 1860s, though apparently not perfectly, and not without building up some debt. Fortunately, by

the time someone needed to step up, eldest son Elias Martin had come of age and was able to hold

power-of-attorney. Court File 836 contains a petition dated 17 January 1870 asking that guardianship

be granted to Elias, who then used this authority 28 April 1870 to sell a parcel of family acreage to

Miles Smith (whose grandson Ray Burnette Smith would eventually marry Nathaniel’s granddaughter Vivian

Blanche Martin), raising $1400 to pay debts for the estate of “Nathaniel Martin, Insane.”

Court File 1446, dated 18 February 1878, contains an authorization to commit Nathaniel to the Mendota

State Hospital for the Insane in Madison, visitors other than his wife not allowed without court

approval.

What on earth happened? Customers and business partners continued to have confidence in Nathaniel. Cyrus

Woodman did additional business with him well into the mid-1860s. Nathaniel was well thought of and

often praised in lasting public records. Hannah had six more kids with him after 1858. He obviously did

not spend much of his life in guardianship. The incidents of hysteria appear to have been short-lived and

atypical of him. Yet the petitions cannot be dismissed as legal ploys by others to seize control of

Nathaniel’s wealth -- though his stepfather might in fact have had just such nefarious designs in his

heart. The problem, whatever it was, was real.

Perhaps the symptoms arose from alcohol poisoning, either

from too much liquor or from liquor that was

badly made. Perhaps it was some other kind of poisoning. The environment of pioneer-era Martintown did

have its toxins. Many southern Wisconsin men worked in the Lafayette County lead mines and became

thick-witted from exposure to the metal. It is ironic that Jeremiah Frame was chosen to act on

Nathaniel’s behalf in 1858, because Jerry was one of those Lafayette County lead miners and therefore

himself at risk of impaired mental function. It is tempting to explain Nathaniel’s affliction as the

result of toxic build-up in his bloodstream from the contaminated water (and/or the fish) of the

Pecatonica River. Martintown was downstream from the mines. However, the symptoms of lead poisoning are

typically such things as lethargy, pain, nausea, and confusion, rather than the sort of manic and/or

hysterical behavior Nathaniel exhibited. Nathaniel’s problem may well have been genetic. His daughter

Jennie Edith Martin Hodge was committed to Mendota State Hospital in the late 1870s and died there in

1882, at age thirty-one, under circumstances that suggest she committed suicide. Julia Beard Martin

Savage was temporarily confined at Bangor State Hospital in Maine in her late middle age. At least two

of Nathaniel’s grandchildren committed suicide, and so did at least two great-grandchildren. Others had

troubles of the brain, running from migraines to anatomical aberrations.

Perhaps the symptoms arose from alcohol poisoning, either

from too much liquor or from liquor that was

badly made. Perhaps it was some other kind of poisoning. The environment of pioneer-era Martintown did

have its toxins. Many southern Wisconsin men worked in the Lafayette County lead mines and became

thick-witted from exposure to the metal. It is ironic that Jeremiah Frame was chosen to act on

Nathaniel’s behalf in 1858, because Jerry was one of those Lafayette County lead miners and therefore

himself at risk of impaired mental function. It is tempting to explain Nathaniel’s affliction as the

result of toxic build-up in his bloodstream from the contaminated water (and/or the fish) of the

Pecatonica River. Martintown was downstream from the mines. However, the symptoms of lead poisoning are

typically such things as lethargy, pain, nausea, and confusion, rather than the sort of manic and/or

hysterical behavior Nathaniel exhibited. Nathaniel’s problem may well have been genetic. His daughter

Jennie Edith Martin Hodge was committed to Mendota State Hospital in the late 1870s and died there in

1882, at age thirty-one, under circumstances that suggest she committed suicide. Julia Beard Martin

Savage was temporarily confined at Bangor State Hospital in Maine in her late middle age. At least two

of Nathaniel’s grandchildren committed suicide, and so did at least two great-grandchildren. Others had

troubles of the brain, running from migraines to anatomical aberrations.

Genetic or environmental, the 1858 incident was possibly the first time he had behaved so strangely, and

it is worth wondering if there was a precipitating event. A likely culprit would be the bank panic. It

hit the nation unexpectedly. Nathaniel would have in the early autumn of 1857 been thinking of himself

as a thriving Lord of All He Surveyed sort of figure, and a few short weeks later might have perceived

himself as ruined. The shock may have unhinged him. Yet there may have been another, more personal

development that acted as the trigger. Notice whose name is not mentioned in the court proceedings

as a potential guardian? Isaiah Martin. The two brothers had been each other’s right-hand-men throughout

their adult lives. But by early 1858, Isaiah was apparently no longer part of the scene in the village of

Martin. This would mean he had proceeded on to the next chapter of his life, departing with wife Mary Gibler

Martin and their little girl Minnie and Mary’s brother Jesse and his family for Van Zandt County, TX.

Jesse remained the primary brother figure in Isaiah’s life from that point on, taking the place Nathaniel

had occupied. The two households were established on adjacent farms in Texas and then, after worries about

Indian predation chased them out in the early 1860s, were reestablished on adjacent farms in Perry County,

MO. The latter locale was where Isaiah died in 1873, collapsing and dying as he attempted to pass through

his garden gate. It is quite possible he and Nathaniel never laid eyes on one another even once during the

sixteen years leading up to that death. The only hint suggesting that contact was maintained is that

Nathaniel and Hannah’s daughter Emma ended up marrying Cullen Penny Brown. Cullen, who like Isaiah had

sawmill expertise, was raised less than ten miles north of Isaiah’s home in Perry County. It could be that

Emma met Cullen by going to spend some time with her uncle as a teenager in the early 1870s. (This is

speculation -- there is no direct evidence Emma made such a visit.)

Did Isaiah and Nathaniel have a falling out? Whatever went on, it appears to have been sudden. A surviving

letter written 17 November 1857 by John Warner, father of Nathaniel’s future son-in-law of the same name,

mentions that Isaiah was nearly done dredging out the mill race to increase the water flow at Bradford &

Hicks’s mill in Winslow (the successor of Bradford & Loring’s mill). So Isaiah was around in late November,

1857, but seems to have vanished by early January, 1858. (John Warner was gone by then, too, having suddenly

died less than eight weeks after writing the letter.) Might it have been Nathaniel’s fault Isaiah went away?

Was Nathaniel left with a case of unresolvable guilt? Maybe there was no actual rift, and Isaiah simply

decided that he and Mary would go along with Jesse and Rebecca Gibler as the latter went in search of greener pastures. Inasmuch

as Isaiah had been Nathaniel’s anchor, the combination of his departure and the bank panic happening

within a short span of time perhaps was more than Nathaniel’s psyche could handle. Impossible to say. We

are left with the mystery. We can be sure, though, that one way or another Nathaniel deeply felt the

absence of his brother.

With the troubles, and the departure of Isaiah, the village of Martin no longer grew by leaps and bounds

the way it had from 1850 to 1857. However, business at both the grist mill and sawmill was steady and for

the next few years Nathaniel did try to expand his holdings, if not with the same degree of success. In the

postscript of a letter written 3 June 1861 by Cyrus Woodman, Cyrus recommends that Nathaniel purchase the

same model of modern, efficient stove that Cyrus had recently installed in Mineral Point. Cyrus points out

that it would be appropriate for the new Martintown woolen mill, and that there was still time to get one